Chief Editor at Nerdish

The History of Tea: How We Started Drinking the World's Favourite Brew

People drink about 2 billion cups of tea daily: only water is more popular. There are over 3000 varieties of tea, spread all over the world. Let’s explore the history of tea!

Since the beginning of tea culture, China has been a major tea producer, and Japanese culture is famous for its tea ceremonies. In the Western world, tea is closely associated with Great Britain and its 5 o`clock ritual. But there is more to tea than porcelain cups, sugar, and a scoop of milk: there was rivalry, theft, war, and drugs involved.

In this article, we explore the history of tea, tracing its journey to Europe, its association with Britain, and the introduction of tea in bags. In 2020, China dominated the tea market with almost $79 billion in revenue.

How Did the History and Culture of Tea Begin?

Everything in this story started when the Chinese discovered tea around 2000 BC during the Qin dynasty. The story tells that a tea leaf fell into a cup of hot water that belonged to Emperor Shen Nung. He tried and enjoyed a beverage, thus starting the whole tea production. Around the 8th century, a monk, Lu Yu connected tea with Buddhist ideas of harmony. He also wrote Cha Jing (The Classic of Tea) – the earliest known guide to tea culture from growing to brewing and serving.

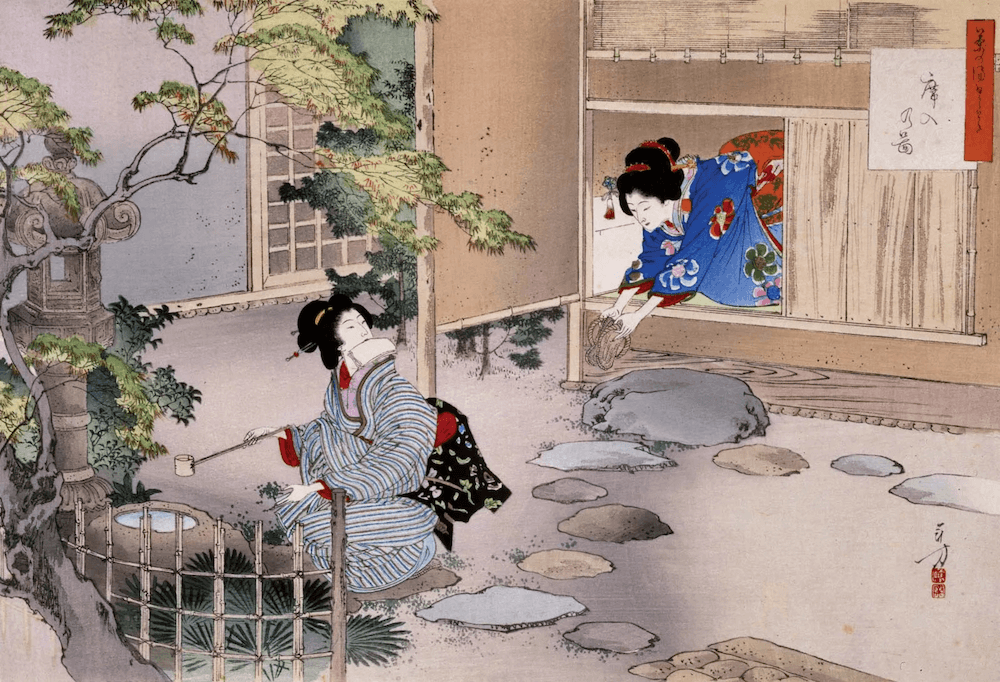

Buddhist monks and traders brought tea to Asian countries. In Japan, tea was first used in religious ceremonies and was popular among monks. One of them, named Eisai, wrote a book on the benefits of tea in the 13th century. Samurais were the first to appreciate tea for its refreshing properties, especially to cope with hangovers. Soon, tea houses opened in big cities, where traditional tea ceremonies emerged. Eventually, the fame of this refreshing beverage reached the European continent.

Until the 17th century, there was only green tea. Then, the Chinese invented a fermentation method to make black tea from green tea.

At the end of the 15th century, Europe entered the Age of Discovery through expeditions, colonization, and intercontinental see trade. The vessels from the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and England reached the coast of China, starting a new market. Europe was really interested in importing Chinese goods: porcelain, silk, spices, and tea. There are only two words for tea in the world, which are derived from the same Chinese hieroglyph. Depending on the province, it is pronounced “te” or “cha.” Europeans who bought products from “te” pronouncing territories adopted this name (British, Dutch, Italians). Others, like the Portuguese, exported tea from the port of Macau, where it was pronounced: “cha,” and adopted it in their language.

How Did the United Kingdom Become a Tea Country?

British Queen Elizabeth I gave her blessings to launch the East India Company – an exclusive trader with the Far East and one of the world’s first monopolies. The Company was free to make international deals, open sub-companies abroad, and conquer territories. At one point, the East India Company had its own army with 260 thousand soldiers, which was 2 times more than the Crown had at the time.

There is a practical explanation for British tea with milk combo. Tea was traditionally served in Chinese porcelain cups, so thin and delicate they could easily crack from hot water. Cold milk was poured before tea to prevent the problem, and gradually, it became a thing of a taste.

Tea was very expensive: in 1665, one pound went for 16-50 shillings, depending on quality. To compare, the weekly salary of a workman was 20 shillings. Servants started to dry tea leaves from their masters’ pots and steep them again. Soon, the black market of recycled tea spread all over the country so that the lower classes could feel themselves aristocrats with cups of tea in their hands. By the end of the century, England became a tea nation. In 1700, England imported 70 pounds of tea, but in 30 years, it was a million pounds.

In British America, tea was equally appreciated but had its ups and downs. First, the Parliament passed the Act that prohibited the colonies from buying tea other than from Britain. Then, it reduced importing taxes from the East India Company. So, British America couldn’t legally buy Dutch tea (which was much cheaper) and didn’t get income from import taxes. In 1773, members of the political organization “Sons of Liberty” came to the Boston port and tossed a load of tea right into the water as a sign of protest. This event was nicknamed Boston Tea Party.

The tea boycott continued during the Revolutionary War (1775-83). Everything openly British was considered unpatriotic, including tea. So, Americans ultimately switched from tea and became the coffee nation. Every 4 out of 5 cups of tea drank in the USA is iced tea.

How Britain Began Growing Its Own Tea

Other changes were coming up now in the Asian market. China wasn’t interested in importing any European goods except silver. Here is when East India Company decided to give the Chinese something that they would need time and again, something even more desirable than silver coins – drugs.

England needed lands and cheap labor to grow exorbitant amounts of opium. Now, remember the army of the East India Company? In no time, it conquered the Northern part of India and started extensive cultivation. Here comes a passage about horrific working conditions, bad food, lack of water, and child labor – you get the picture. Anyhow, by the 19th century, England was in full stock with the product ready to ship to China.

Opium created a disaster in China: in the 1800s, almost 30% of men were opium addicts. China tried to suppress drug trading several times, finally dropping the whole batch into the sea. In response, England sent warships and started the Opium Wars (1839-42) and (1856-60). Opium-addicted low-willed Chinese soldiers weren’t that effective in battle, so they lost both wars, gave up Hong Kong, and opened more ports for export.

Opium Wars opened more possibilities for the tea trade, but Britain was still in a dependent position. So, they decided to grow their own tea and overthrow the Chinese monopoly. They already had a piece of land in colonized India, which was suitable in all aspects: the climate, soil, and cheap labor. The only thing missing was a tea, a top-secret no-export plant.

So, Britain hired a Scottish plant hunter Robert Fortune who disguised himself as a peasant and worked at the Chinese plantation for almost 2 years. During this time, Fortune learned the process of growing, peaking, and drying tea. Also, he found out that green and black tea varieties came from one plant. Finally, he tore out tea sprouts and brought them to the British vessels. From there, tea went to India and was re-planted in the new spot. In this way, England created their own tea industry in India.

Modern Tea History: When Did We Start Using Tea Bags?

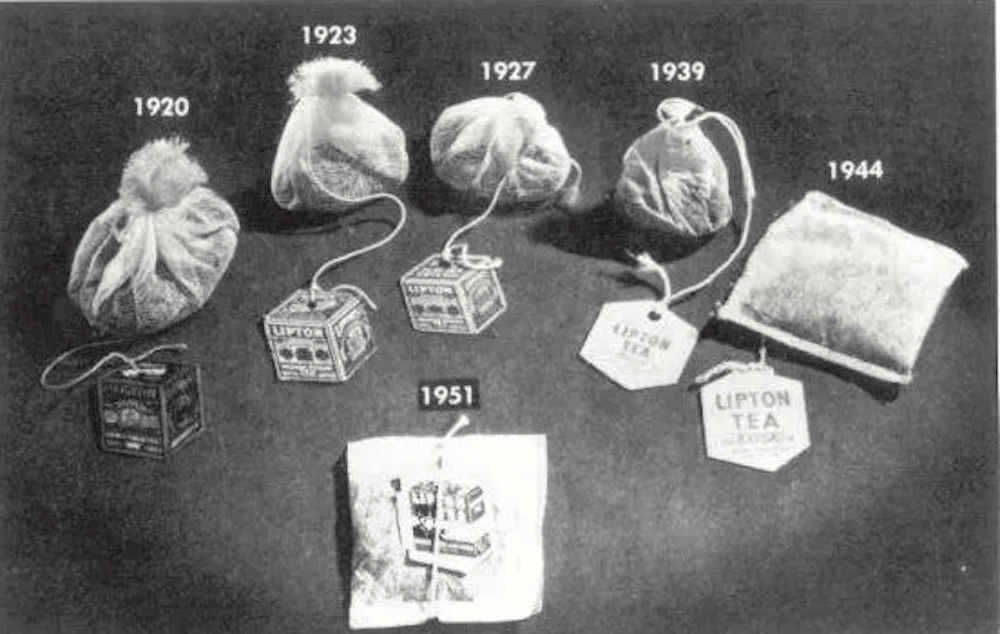

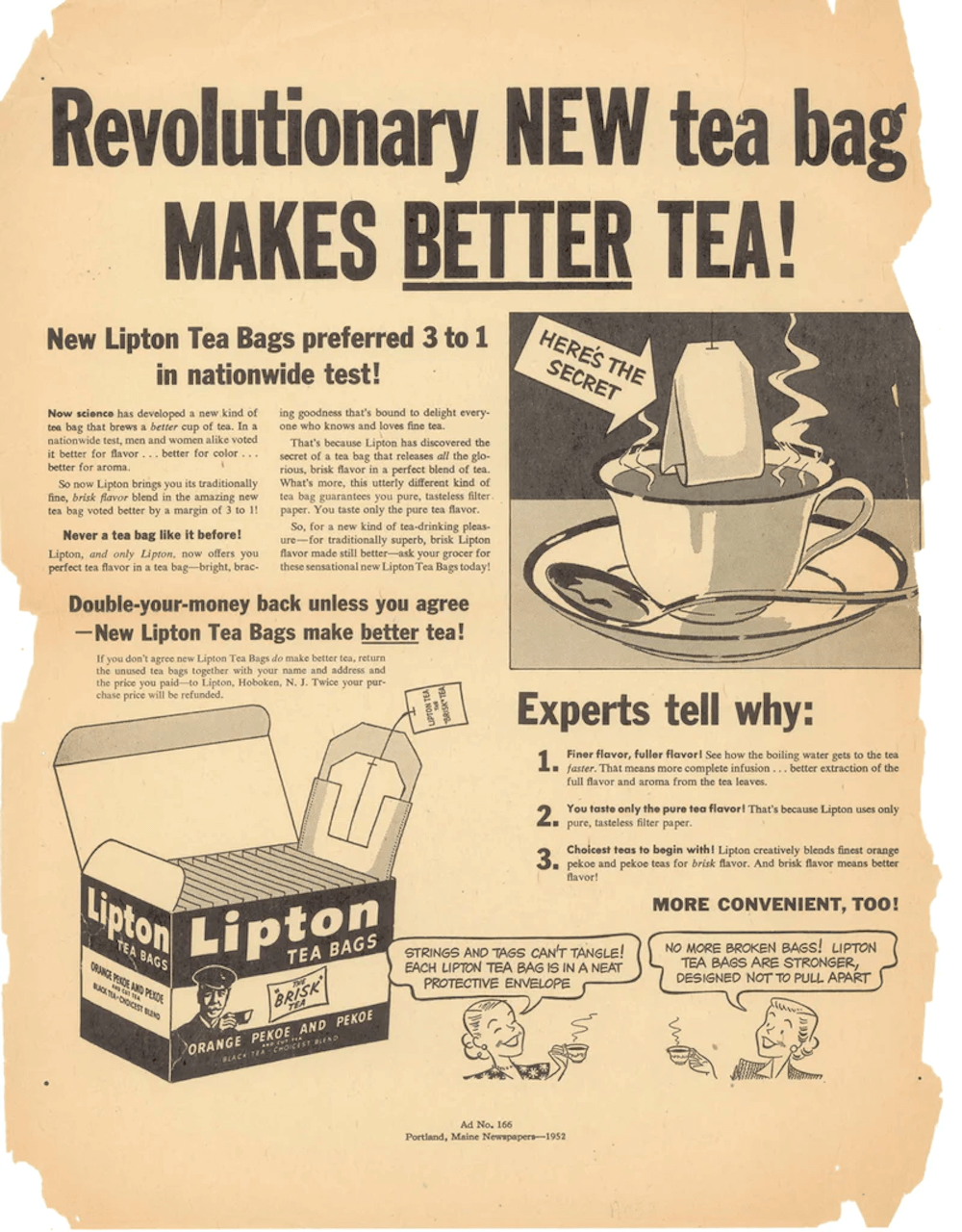

Until the early 20th century, people prepared tea simply by pouring hot water over loose leaves in a pot. In 1901, two Americans, Roberta Lawson and Mary McLaren, received a patent for a tea leaf holder from woven cotton fabric. But it was Lipton company that popularized portioned tea in bags. Lipton changed the design of the bags many times until the introduction of a special “flo-thru” bag in 1952.

The main advantage of the tea bag was convenience and time-saving: one didn’t have to clean the pot/cup of loose leaves afterward. Plus, a tea bag already had a precise portion of leaves needed to brew the drink, so it reduced waste. People were slowly adopting the novelty and its several improvements until tea bags became omnipresent.

In the 1920s, the manufacturers started to cheapen tea and put the worst one into the bags. Consequently, bagged tea got a bad name and a reputation as a low-quality product. So much so the British didn’t consider it worth buying. In the 1960s, only 3% of all tea was brewed in teabags.

Eventually, the product was promoted as one to make life easier without cleaning the pot, and the quality and variety became better. Step by step, teabags skyrocketed to 96% in the 2000s in the UK.