Art Deco Explained: Why It Remains Timeless

Even if you are inept at arts, there is one example of the Art Deco style that you’ve certainly seen. The legendary Oscar statuette was created in 1928 by Cedric Gibbons, art director at MGM movie studio.

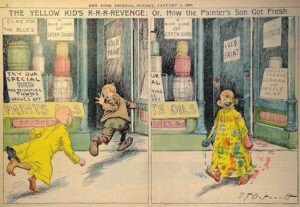

Apart from that, Art Deco has inspired the design of a vast array of objects: from colorful advertisements and magazine covers to functional items such as clocks, furniture, jewelry, flatware, cars, and even ocean liners. It is visually pleasing but not intellectually threatening; unlike its earlier counterparts Art Nouveau and Cubism, it had no philosophical basis and was purely decorative.

What is Art Deco?

Art Deco flourished in Paris in the 1920s, and in the following decades, it manifested within architecture, sculpture, painting, and decorative arts around the world.

The name of the style was coined in the 1960s after the name of a great exhibition that took place in Paris in 1925. “Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts” was shortened in French to Arts Décoratifs or Art Déco. The goal of this exhibition was to challenge the hierarchy of the visual arts and prove that decorative arts are as valuable and meaningful as classical painting and sculpture. The Art Deco exhibition featured over 15,000 artists and designers, and it was a huge success: in seven months, it hosted more than 16 million visitors. It was also the catalyst of the Art Deco movement.

In general terms, Art Deco represented modernism turned into fashion. It blended arts with the craftsmanship and found its use primarily in textile, interior, furniture, fashion design, and architecture.

The Art Deco laid roots in the buildings of Paris and New York, but also of Sydney, Havana, Mumbai, and Jakarta. Less strongly, this style can be found in painting, sculpture, and graphic design.

If you were to name one painting as the epitome of Art Deco, look at Tamara de Lempicka’s portraits of European nobility of the 1920s. Her works balance a thin line between fine art and graphic design—a typical thing for Art Deco.

Read on to learn the features that would help you to recognize Art Deco, as well as the style’s historical roots in ancient cultures.

How to recognize Art Deco?

Whereas the Art Nouveau style (1880–1910s) derived its intricate forms from nature and eulogized the merits of the hand-crafted, the Art Deco aesthetic played up machine-age sleek and streamlined geometry. Art Deco was also called the “Cubism Tamed,” referring to its fascination with fragmented, abstract forms without going to extremes.

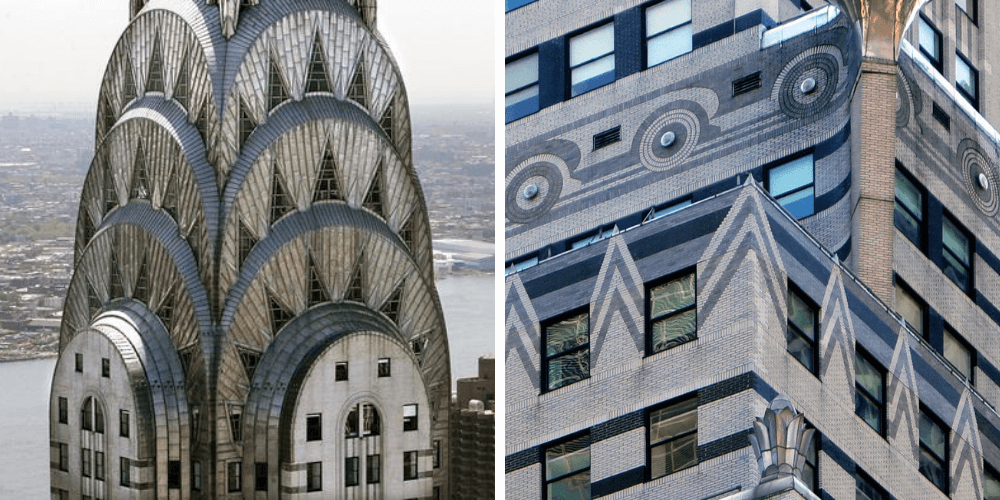

The Art Deco works are symmetrical, balanced, often simple, and pleasing to the eye. They frequently use zigzagged, trapezoidal, triangular shapes, stepped forms, chevron patterns, sweeping curves, and sunburst motifs. The distinguishing features of Art Deco style are simple, clean shapes, and its main visual characteristics derive from repetitive use of parallel lines, linear and geometric shapes.

The Art Deco aesthetic was careful to balance splendor and practicality. Bright, lavish colors are synonymous with this period, but all in all, American Art Deco is less ornamental than its European counterpart. In both versions, characteristic motifs involved sun rays, animals, nude female figures, and foliage, all in conventionalized forms.

But if the formative influences on Art Deco were recent Cubism and Art Nouveau movements, the decorative ideas mostly came from the ancient cultures.

What Art Deco took from Ancient Egyptian, Mayan, and African aesthetics

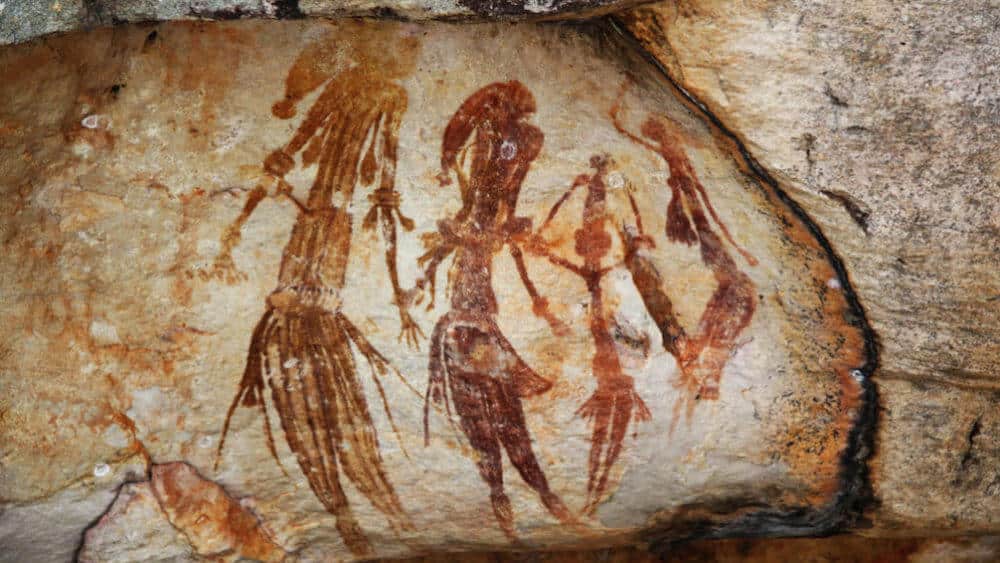

Art Deco artists hunted for the exotic cultural elements they could integrate into their artworks. The second quarter of the 20th century marked the demise of European colonialism, with Africa, Mesoamerica, and Egypt being the primary sources of cultural appropriation. The stylized, geometric nature of their visual arts dovetailed nicely with other aspects of the Art Deco style.

In 1922, after British archeologists discovered the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, the aesthetics of Ancient Egypt took hostage European artists and designers. Generic Egyptian imagery such as pyramids, hieroglyphics, and scarabs proliferated everywhere, from cinema façades to clothing. Motifs of lotus flowers, tropical birds, camels, and figures in a characteristic Egyptian pose (head in profile, shoulders, and hips front-facing) became commonplace.

The French jeweler Louis Cartier expressed his admiration of Ancient Egypt in a famous Egyptienne chiming clock. He mimicked Egyptian temple architecture and carved the clock’s base from Lapis Lazuli, a traditional Egyptian decorative material. A more public example is Eric Gill’s relief sculpture outside the BBC Broadcasting House in London (1933) which imitated a winged scarab.

The Egyptian style profoundly influenced the Art Deco design of furniture, jewelry, and clothing. A short female haircut, an obligatory attribute of the roaring twenties’ fashionable girls, was also an imitation of Egyptian hairstyle.

Another Art Deco source of exotic imagery was Africa. The abstract geometry of African sculptures and textiles was easily accommodated for the modern eye. African-like figures and zigzagged ornaments turned out to be a popular Art-Deco decorative motif, as seen in Sonya Deloney’s costume designs.

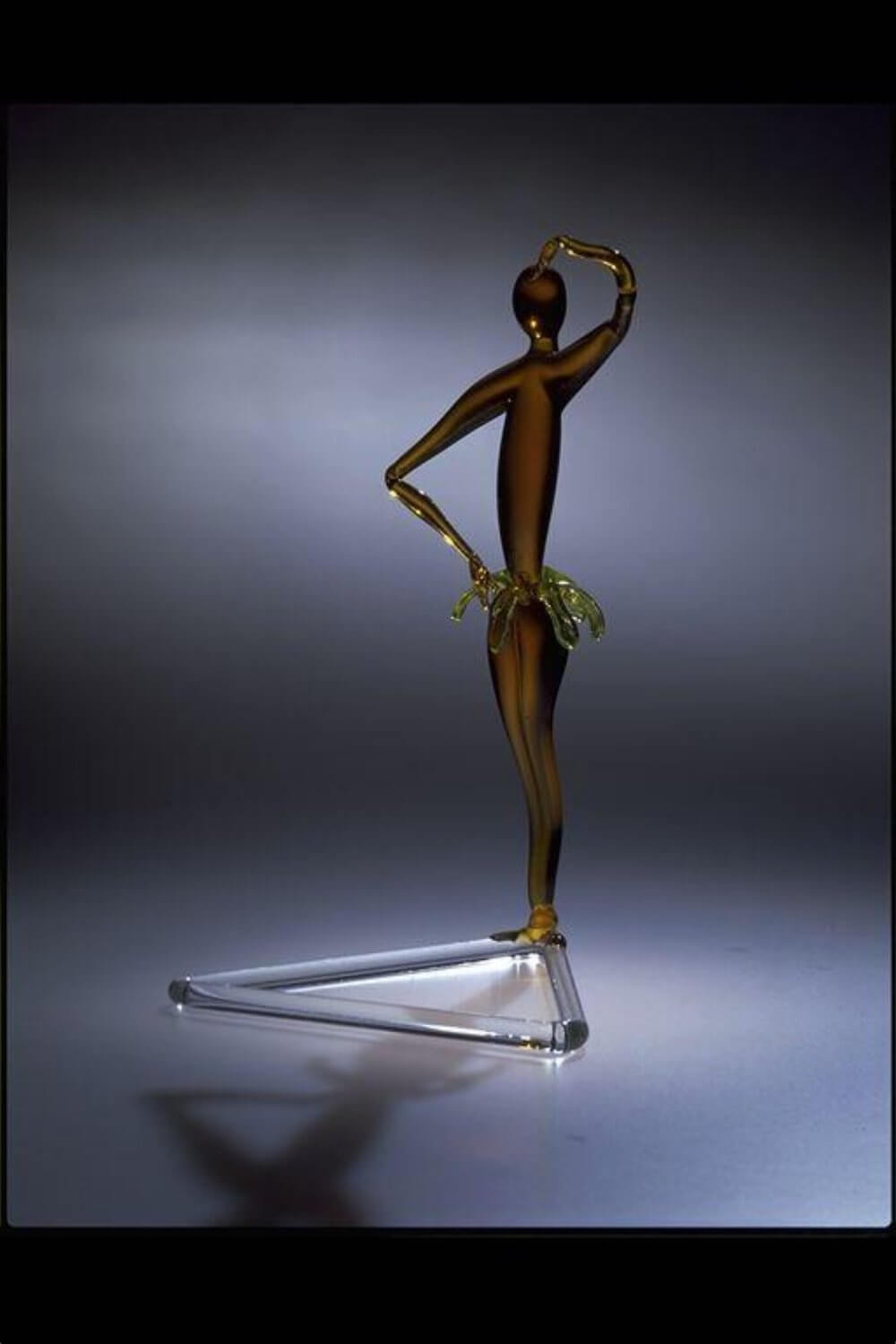

In 1925, Josephine Baker, the African-American dancer, became a sensation in Paris. Her erotic movements and alluring costumes, especially a skirt made of bananas, turned her into a design icon. She appeared in many Art Deco objects, such as Fritz Lampl’s lamp-worked glass statue.

While Egyptian and African motifs were more popular in Europe, America drew inspiration from its own past. Whereas most Aztec ruins were explored long before the 1920s, archeological discoveries of the Maya were fresh. The jungles of the Yucatan revealed abandoned cities and temples. Zigzagged outlines of Mayan ziggurats and pyramids reflected in brand-new American buildings. Iconic American architect Frank Lloyd Wright frequently incorporated Mayan motifs: his Hollyhock House (1922) is a beautiful example of the Mayan Revival style, a trend within American Art Deco architecture.

We can trace more ancient influences in couture and design of the American 1920s, and it’s hard to tell whether they have Aztec or Mayan origin. The distinction was not significant at that time for fashion designers. They consumed fresh images of ancient artifacts and digested them into generically exotic ideas, such as a starburst motif of Art Deco jewelry and panther or jaguar as a popular Art Deco image.

These cultures weren’t only celebrated in imagery but had an impact on the choice of material too. Art Deco furniture designers frequently chose tropical woods for their sensuous effects, as seen in Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann’s lotus dressing table (1923). It was made of amaranth and andaman padauk woods and encrusted with luxurious ivory and ebony marquetry, associated with the opulence of the past.

Ancient cultures inspired the Art Deco style in many ways. But what makes its charm unique is that Art Deco combined fascination with the past and orientation towards the future. It was influenced by Egyptian sphynx and Aztec sunstones, but it also was enchanted by modern ships, trains, and motor cars.

Art Deco technological luxury and the mass-market future

Initially, a luxury style (and defiance against the austerity of World War I), Art Deco employed lavish materials like silver, crystal, ivory, jade, and lacquer. Art Deco’s design combined technology and luxury, making it especially suitable for the interiors of cinemas, train stations, and ocean liners. It endured throughout the Depression due to its practicality and simplicity and its suggestion of better times ahead. However, the new economic reality of the 1930s influenced the style, turning it to cheaper materials and more simple forms.

The severe economic breakdowns of the late 1920s and early 1930s forced designers and architects to use cheaper and mass-produced materials. They replaced gold with chrome and granite with concrete, eagerly employing new industrial materials, such as aluminum, stainless steel, vita-glass, and other plastics.

The most renowned Art Deco plastic, Bakelite, was widely used for radios, telephones, and jewelry. Designers cut their budgets and switched to smarter practical ways, still actively reproducing decorative effects from the 1920s. Art Deco retained its reputation for being a “rich” style, as even mass-produced items from the 1930s seemed expensive and luxurious. The artists catered to the growing middle-class taste for a style that was affordable yet elegant, glamorous, but functional.

The Art Deco era was obsessed with technical progress. Expensive designer furniture of that time incorporated hi-tech aesthetics, like armchairs with built-in lamps or retractable ashtrays. Modern vehicles were frequent attributes of artworks and sources of inspiration for their creators.

Raymond Templier, the famous Art Deco jeweler, said he found ideas for his pieces in wheels, cars, and mechanisms. One of the later varieties of Art Deco, known as the Streamline style, was a literal homage to the streamlined shapes of anything that flew, sailed, and rode fast. Buildings, radios, kettles, and lighters imitated forms of ships and planes.

Art Deco architecture embodied scientific progress and the consequent rise of technology and speed, as seen in skyscrapers and other large-scale buildings.

The New York Chrysler Building created by William Van Alen between 1928 and 1930 featured the newest technology: automobile friezes in the brickwork and radiator caps jutting out from the corners. At the same time, its great crown with seven layers of crescent setbacks inset with triangular windows is reminiscent of ancient zigzags and sunburst.

Art Deco fell out of fashion when the Second World War hit on Europe and North America. The new austerity of wartime caused it to seem decadent, outdated, and gaudy. It was revived though in the 1960s, as its global visual language responded well to the requirements of the rising consumerism.

Many cities made efforts to preserve the historic Art Deco buildings, converting some of them into cultural centers. The turn of the 21st century saw the resurgence of century-old motifs in a style called Neo Art Deco.

Rooted in ancient cultures, the aesthetics of Art Deco speaks to the hearts of people all over the world. That’s why the heritage of this decorative style is still present today, mainly in the field of fashion, product, industrial, and graphic design. Course block Course block