Drawing: from a child’s doodles to Da Vinci’s masterpieces

Drawing seems the easiest of arts, only pen and paper required. However, it has been called “the father of arts” for a reason.

What makes drawing so unique?

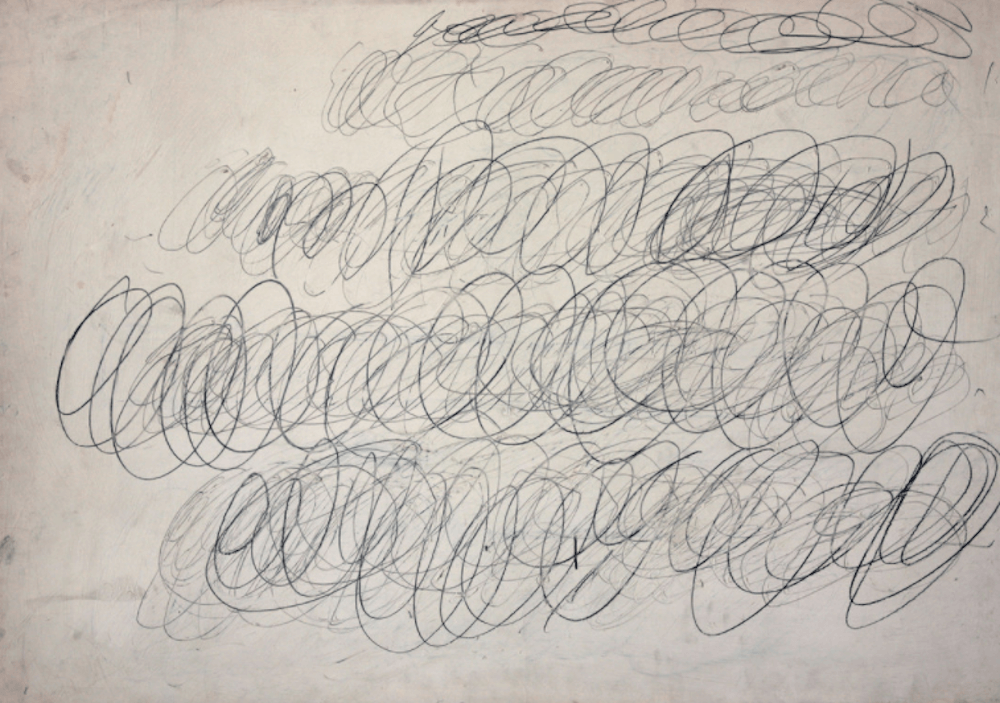

Many people consider drawing the most basic form of visual art. Children start drawing at a very young age, not concerned with an adult notion that only a selected few can be artists. As children draw, not only do they have fun and develop their fine motor skills—they learn to understand concepts and ideas.

For an adult, a 3-year-old’s stick figure may not look much like art, yet it still requires abstract thinking and understanding of concepts on the level only humans are capable of. The world around us does not usually manifest in simple lines—so the images of the stick figures are produced entirely by our minds.

Renaissance painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari described drawing as the “father of three arts” (painting, sculpture, and architecture). What he meant is how precisely drawing can express an artist’s inner conception. For Vasari thus, drawing was the very essence of the visual arts.

In the Western cultural tradition, there are other ways in which drawing serves as a basis for painting, sculpture, and architecture. It is a simple means to express one’s creative ideas; it is easy to correct and experiment with; it requires relatively cheap materials. All of that led drawing to become a preparation stage for other kinds of art.

Since Raphael, many painters started their work from roughly drawn sketches, gradually developing them into elaborate drawings, which they presented to their patron for approval. Only after that, the painter started making the painting itself. Apparently, this process has influenced art education in general—as even now, teaching art usually begins with drawing.

However, being the foundational form of art does not guarantee being the most highly valued one. Due to its preparatory role, drawing has been subordinated to painting and sculpture for many centuries. Fortunately, it gradually came to be respected as an independent form of art.

As you may know from our topic “What is art and how to enjoy it,” we can classify visual art by medium and means of artistic expression. Graphics are the kind of two-dimensional art whose primary method of expression is a line (painting is the one mainly expressed through color). Graphics are further subdivided into drawing and printmaking. The former produces unique works of art, and the latter uses various techniques to replicate it (though usually not to an infinite amount).

The distinction between drawing and painting is sometimes tricky. The line separating the two is not always easy to draw (pun intended). Perhaps, it would be more accurate to place every visual artwork on a spectrum. Classical mono-colored (black, gray, red, or brown) contour drawings are on one end of the spectrum, and the full-colored paintings completely covering the support material (canvas or wood) are on the other. Drawings made with colored markers or pencils that do not fill the entire surface with opaque colors will be much closer to the drawing end of the continuum.

Pastel works with large, fully colored areas would be several steps closer to painting but still considered by many art critics as drawings. At the same time, full-colored miniatures from medieval illuminated manuscripts and watercolor works are often recognized as paintings.

The distinction between drawing and painting greatly depends on cultural conventions. Thus, it is more common to acknowledge the uniqueness of drawing in the Western tradition: some cultures (we will explore them later in this topic) don’t distinguish between drawing and painting. On the other hand, the post-Soviet practice generalizes any artwork on paper as “graphic arts,” though pastels and watercolors usually receive a subcategory of their own.

All in all, it is best to listen to the artist themselves: they can decide and tell us whether their art is drawing or painting!

Drawing materials

For drawing, you need support (that is, the surface), tools, and coloring agents. In some instances, one thing can be both a tool and a coloring agent (like chalk or charcoal); these things are different when you use brush and ink. Here we’ll explore some of the most widely used materials—and their sometimes surprising histories.

Supports

Millennia ago, people started drawing on stone, making the now-famous cave paintings (or would it be more accurate to call them cave drawings?).

Historically, people also drew on wood, clay, cloth, and other surfaces. Chinese artists preferred to use silk, whereas their medieval European counterparts made drawings and color illustrations on parchment made from sheep or goat skins.

However, for drawing to reach its full potential, three significant events had to happen. The first was the invention of paper in China about 200 BCE. The second was the spread of invention: despite all attempts to keep paper-making in secrecy, the Arabs mastered this crucial craft in the late 8th century CE—and later, the Spanish got it in the early 12th century. The third major event was the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440: it put paper in high demand, which in turn prompted its high supply. Since then, paper has been the primary drawing support for artists around the world.

Tools and agents

Artists used burnt sticks of charcoal for artistic purposes as early as for the cave paintings/drawings of Chauvet some 30 000 years ago. In the European antiquity and Middle Ages, people widely used charcoal sticks from a grapevine, maple, or willow for preparatory underdrawings when painting murals. Today, every art supply store has its stock of ready-for-use charcoal sticks.

For many people (odds are, you are one of them), pencils come to mind as the first thing to associate with drawing. However, pencils became a thing only after 1565, after a vast deposit of graphite (a crystalline form of carbon) was discovered in England. By the end of the 16th century, people learned how to encase graphite sticks in wooden cylinders—and pencils have remained largely unchanged ever since as the most popular drawing implement.

Before graphite was discovered, artists often drew with metalpoints: pieces of lead, tin, or silver wire, attached to holders or even fitted into a wooden casing. Renaissance artists preferred silver to other metals, as silverpoints allowed for finer details. All metalpoints require a specially prepared abrasive surface: for example, a layer of bone dust added onto the paper. On the prepared surface, metalpoints leave thin gray lines that look similar to the ones left by pencils. However, you cannot erase these lines—so, it is impossible to make a quick sketch this way. To some extent, pencils became the opposite of silverpoints, despite the superficial similarity.

Generally, ink is any pigmented fluid made from oak galls (formed when wasps lay eggs on oak leaves), squid secretion (sepia), and other plant or animal-based materials. However, the most widely used ink is black carbon-based India ink. Despite its name, it was invented not in India—but in China, perhaps as early as 3000 years ago. Thus, it is not surprising that Chinese artists preferred brush and ink to any other drawing tools and coloring agents; in Europe, people usually chose to apply ink with pens.

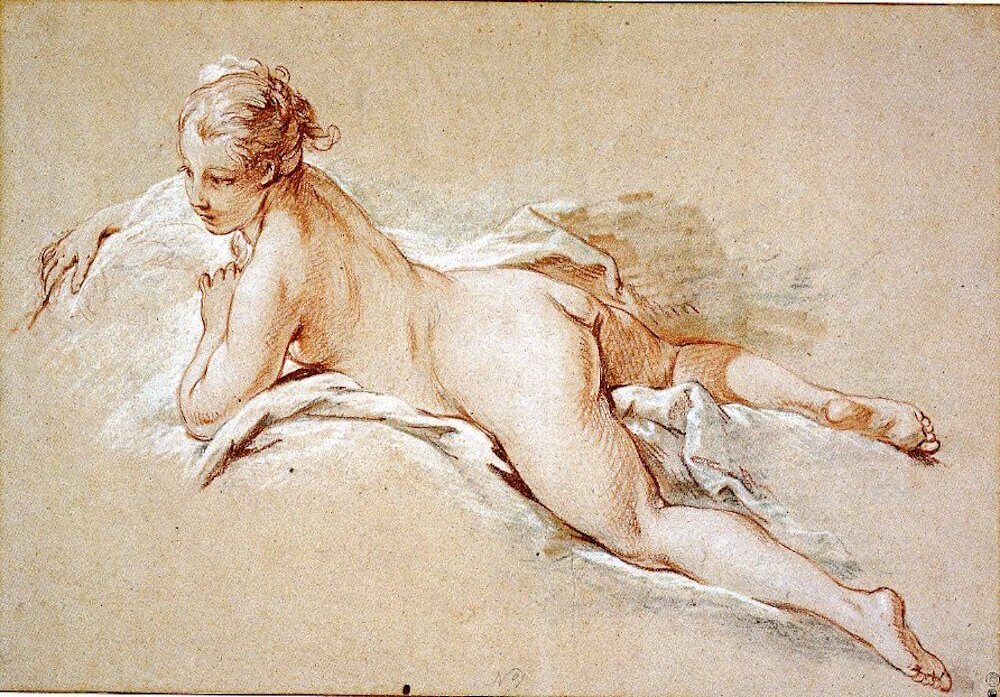

The chalk we use for drawing is not limited to white limestone sticks you might remember from school. Chalk is any pigment from the earth that can apply consistent color and texture. Renaissance artists widely used red, brown, black, and white chalks. Red ochre (so beloved in Paleolithic times) was the main component of sanguine—that is, the red chalk, the most popular drawing medium in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Pastel sticks are, to an extent, the descendants of chalk. Chalks are unprocessed pieces of colored earth pigment—to make pastel, we take the same pigment, powder it and mix it with glue. Pastels come in various hues: from the most delicate “pastel colors” to the bright and luminous ones. Impressionists of the late 19th century loved pastel for its combination of painting-like colors and drawing-like freedom.

Marker pens, so simple in use and beloved by children, are basically small sponge brushes with their own source of color ink. A modern felt-tip pen was invented in 1953; in the early 1990s, Japanese brand Copic started to produce markers for professional illustration and manga drawing.

Explore the tools yourself!

We could write many paragraphs describing the differences between all these tools and agents. However, seeing with your own eyes is better than reading about it—and the best way to see is to try drawing yourself!

No need to come up with an elaborate concept: to experiment with tools and agents, draw something as simple as a tree leaf (or even a hand stencil).

When you try a tool, ask yourself questions. How does it feel to use it? What do you like most? Remember that each tool has its unique subtle ways of use. For example, charcoal needs more textured paper than a pencil. With ink drawings, keep in mind that you cannot erase ink. Pastel and charcoal drawings need a fixative spray to keep them in place—if you forgot to buy one, even a typical hair spray will do!