What makes a person attractive?

We want to spend time with others: but what makes us want it? There are several distinct biological mechanisms of what we generally call “attraction”: let’s explore them!

The biology of attraction

Our brains are very complex, and it can be hard to discern one concrete reason why we want to spend time with a person. Sometimes it’s a mystery even to ourselves! Nevertheless, it is impossible to deny that attraction has a solid biological foundation.

Thus, the first thing to discuss will be the biological mechanism of attraction. Read on to learn more about first impressions and how fast and accurate they are; after that, we will look at how we could influence the process ourselves and possibly become more attractive in the eyes of others.

That said, on to biology: in the simplest terms, our desire to seek other people can be divided into three very distinct categories: lust, attraction, and attachment.

On a personal level, we will often have varying definitions of what each of these three terms means to us; however, the differences are far more clear-cut when it comes to biology.

Lust

Lust is arguably the most basic of these three categories—our desire for sexual gratification primarily drives it. This biological mechanism has a fundamental evolutionary basis—our need to reproduce.

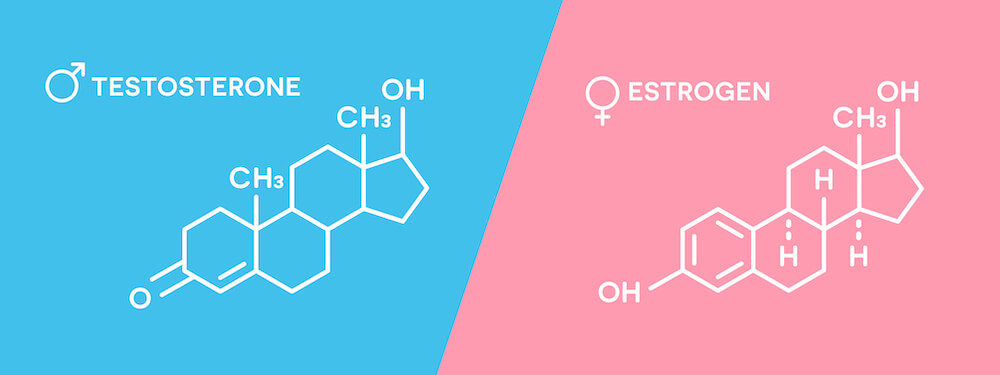

Virtually all living things share this same need to reproduce because this is how they pass on their genes and help facilitate the survival of their species. So, in the most simplified terms, the lust between humans is primarily governed by two hormones: testosterone and estrogen.

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that bridges the nervous system and the endocrine system. In the right situation, it signals to produce these hormones in ovaries and testes. Course block

The more sex hormones we have in our system at a given moment, the more we desire the person we are talking to. As a result, we can become flustered and experience a vast array of emotions. However, sex hormones are not the only ones that rule our feelings. Testosterone and estrogen are often stereotyped as male and female counterparts to each other. But they both play a role in every person’s body.

Attraction

Although lust is oftentimes seen as a precursor to attraction (or something that happens simultaneously), the two are not linked in any biological sense. They can easily occur independently of each other: we can feel attracted to someone without desiring them sexually and vice versa.

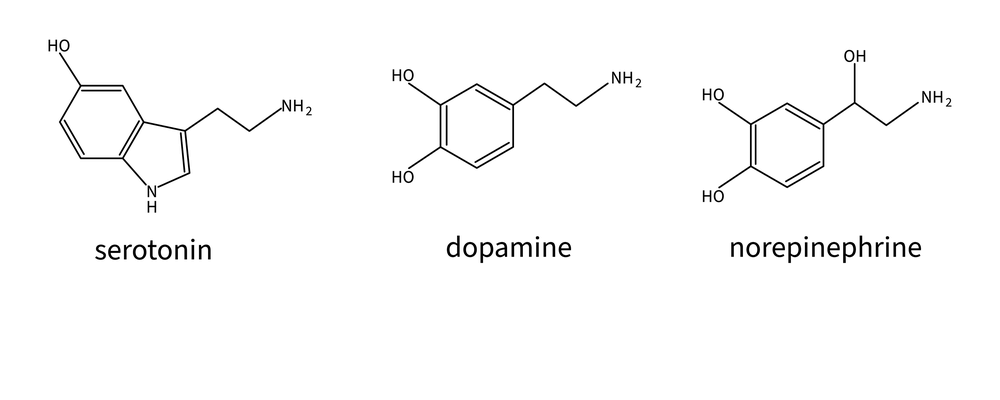

However, it is still in the hormones. The three primary hormones that govern attraction are dopamine, norepinephrine (also called noradrenalin), and serotonin. Whereas the desire for sexual gratification primarily drives lust, brain pathways that control the “reward behavior” are more involved in the mechanism of attraction.

Dopamine is a hormone that drives our motivation. Our brains signal the release of dopamine whenever we perform acts that feel good to us—for relationships, this can range from having sex to simply spending time with loved ones.

Norepinephrine is released during these times as well, serving as a supplement to dopamine. In addition, norepinephrine plays a crucial role in our body’s “flight or fight” response, making it more focused and agitated. Norepinephrine’s link to the “flight or fight” might be the biological reason why we sometimes fall in love so deeply that we find it hard even to eat or sleep.

Compared to dopamine and norepinephrine, serotonin’s involvement in attraction is actually the opposite. Serotonin is the primary “hormone of happiness”: the more we have it, the happier we are. However, some scientists found that attraction might be related to reduced levels of serotonin: and this might be one of the primary causes of our infatuation with others.

Attachment

Attachment can be viewed as a counterpart of attraction that governs non-romantic relationships. The mechanisms of lust and attraction are activated primarily in the context of romantic relationships; attachment deals with other situations like parent-child bonding, friendships, social supporters, etc. Attachment often replaces attraction as the primary driving biological mechanism in long-term relationships.

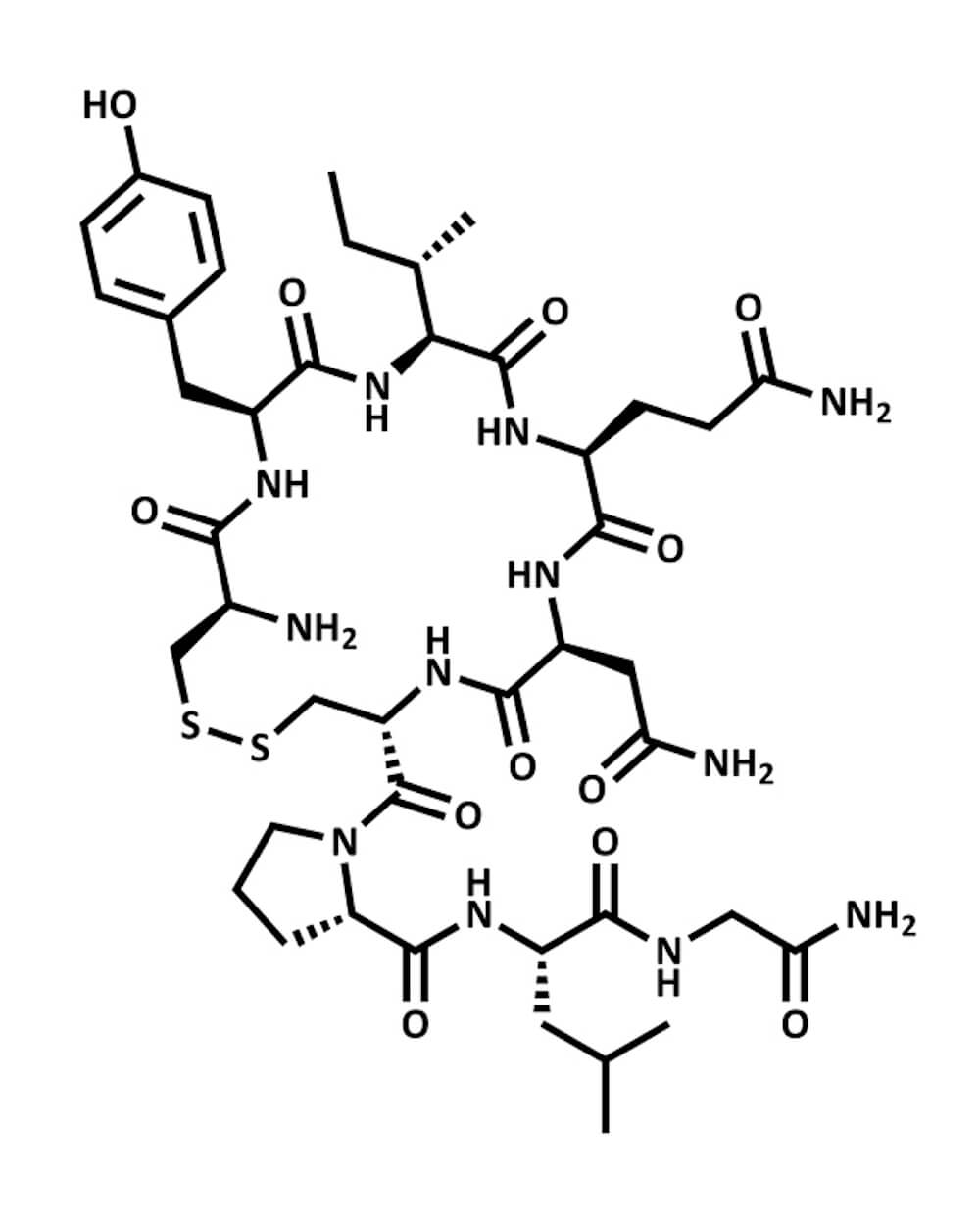

At this point, you probably wouldn’t be surprised to find that attachment is governed by hormones as well. The first hormone related to attachment is oxytocin (however, there are others as well: for example, vasopressin).

Although remarkable amounts of oxytocin are released during sex, this hormone is more notable for the role that it plays in mothers’ behavior. Thus, large quantities of oxytocin are released during pregnancy and breastfeeding, effectively speeding up the process of childbirth, facilitating milk production, and motivating us to hold and protect the child.

Outside of mother-child bonding, oxytocin also fosters the need for human ingroup connections and the desire to form a long-term relationship with a sexual partner.

Do first impressions rule everything? How accurate are they?

No matter how wrong our assumptions about others may be, first impressions quickly take root in our brains and are relatively difficult to shake off even when facing contradictory information.

So, how fast do you think it takes for a first impression to be made? One minute, ten seconds, or one second? Studies have shown that it is much faster than that: people form their first impression of someone in less than one-tenth of a second after seeing their face. For comparison, the average time for a person to blink ranges from 0.1 seconds to 0.4 seconds. So, you can safely say that we are attracted to others in the blink of an eye.

When making a first impression about someone, our brain considers many factors; however, the main ones are the person’s facial features and facial expressions. For example, it has been found that we usually associate joyful facial expressions, feminine features, and rounder faces with trustworthiness. On the other hand, negative expressions, masculine features, and more angular faces will more likely leave a first impression of being less trustworthy.

But don’t count on them too much: many scientists agree that first impressions are made too fast to be particularly accurate in most scenarios. We do not rely on facts or logic in this case; our first impressions largely draw from stereotypes linked with specific physical attributes (like the aforementioned facial features).