What Is So Special About Mona Lisa?

Imagine someone asking random people to name one famous painting. Their answer will likely be the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. And it’s no wonder: in 2024, almost 9 million tourists visited the Louvre Museum in Paris, and around 7 million said they came specifically to see this work. More than just a portrait, the Mona Lisa is a global icon, surrounded by mystery, theories, and centuries of fascination. What makes this painting so unique? And why does it continue to capture the world’s attention?

In this article, we explain how the Mona Lisa became so famous. What is there to know about this artwork, and who was the woman captured on it?

How did the Mona Lisa become so famous?

Leonardo da Vinci moved to France around 1516 at the invitation of King Francis I. He crossed the Pyrenees on a donkey, taking his drawings, writings, and other works with him. Among his possessions was the Mona Lisa painting, arguably his favorite painting. Leonardo spent his remaining years in the Château du Clos Lucé near Amboise, where he died in 1519.

After the artist’s death, the Mona Lisa was sold to King Francis I of France. Though the exact sale price records are unclear, some reports suggest it was sold for 4,000 ducats. Thus, this artwork became part of the royal collection and was displayed at the royal residence in Fontainebleau. In 1689, King Louis XIV moved the Mona Lisa Versailles, which became the primary royal residence under his rule.

During the French Revolution (1789), many royal treasures, including artworks, were seized. Eventually, some were moved to the Louvre, which was established in 1793 in Paris, as part of the efforts to democratize access to culture and art.

In 1797, the Mona Lisa was moved to the Louvre Museum and became part of the museum’s expanding collection of Renaissance masterpieces. Napoleon Bonaparte highly admired this work and hung it in his bedroom in the Tuileries Palace in Paris for several years. However, in 1804, it was returned to the Louvre Museum, where it remained on display for the public.

The artwork was one of several important paintings from the Italian Renaissance, though it wasn’t yet considered the jewel of the collection. It all changed in 1911 after the painting was stolen.

The theft of the Mona Lisa sent shockwaves through Paris and soon internationally. The press played a significant role in keeping the public engaged and invested in the investigation. Newspapers worldwide, from the London Times to the New York Times, covered every twist and turn of the search. The painting had been missing for over two years, and the public became obsessed with finding it.

In the same year, Guillaume Apollinaire, a French poet, writer, and art critic, was arrested because he was suspected of being involved in the theft of the Mona Lisa. He was linked to Honoré Joseph Géry Pieret, who had previously stolen small statues from the museum and once worked for Apollinaire. The poet had also once said that museums should return art to the people, and authorities thought he might be involved.

Some rumors claimed that Pablo Picasso was involved in the theft, as he was too close to Apollinaire, though his involvement was never proven.

The theft remained a mystery for over two years until Vincenzo Peruggia, the real thief, was caught in December 1913 when he tried to sell the painting in Italy. Peruggia worked at the Louvre as a handyman and glassmaker. He had previously helped install protective glass on artworks, which gave him insider knowledge of the museum’s layout and security.

Peruggia’s motive wasn’t just to get rich. He wrongfully believed that Napoleon had stolen the Mona Lisa from Italy during his conquests in the early 19th century, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars (1796–1815), when France looted many artworks from Italy. Hence, this theft was an act of returning the Mona Lisa to Italy as part of its cultural heritage. The painting did make it to Florence, where Peruggia tried to sell it to an art dealer, who alerted the authorities. After being recovered in 1913, the Mona Lisa didn’t immediately return to France. Instead, it was displayed in Florence, Rome, and Milan as an “Italian treasure.”

The Mona Lisa returned to the Louvre Museum in 1914, already one of the world’s most famous and celebrated paintings. People stood in long queues, eagerly waiting to view the masterpiece, and this interest hasn’t changed to this day.

It is estimated that at least 120,000 people visited the museum in the first two days after the painting’s return in 1914.

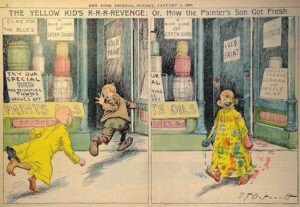

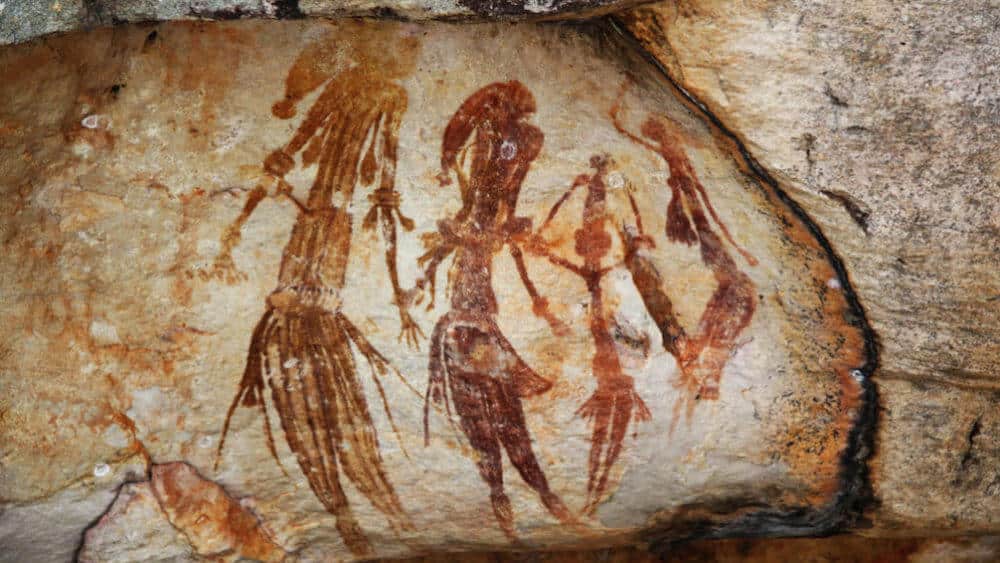

The Mona Lisa isn’t the only artwork that shaped the world. Learn about the powerful message behind Picasso’s Guernica, the early beginnings of visual expression in prehistoric art, or dive into more modern visual culture with the history of comics.

What you should know about the Mona Lisa

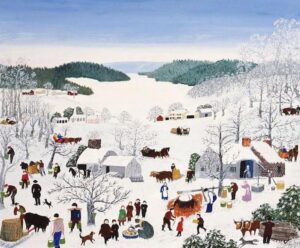

Leonardo da Vinci worked during the Renaissance, which lasted from the 14th to the 16th centuries. This period revived many ideas from Ancient Greece and Rome and reintroduced humanism, which is centered on a person’s value, beauty, and human experience. This shift led to the rise of portraiture, where people became the central subjects of art.

While medieval art was mainly religious, the Renaissance expanded into secular themes, including portraits of scholars, aristocrats, and wealthy merchants. Wealthy families like the Medici in Florence and powerful European merchants funded portrait commissions to showcase their status, legacy, and influence. The first true Renaissance portrait is often considered Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait (1434). His realistic detail, individuality, and psychological depth were the hallmarks of Renaissance portraiture.

Leonardo applied his knowledge of anatomy, light, and perspective to create a harmonious and realistic portrait of the Mona Lisa. He captured lifelike details, soft shading, and natural expressions. Her mysterious smile and gaze suggest inner thoughts and emotions, aligning with humanism’s focus on the mind and individuality.

In the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci applied the linear perspective by painting a detailed landscape with winding rivers and distant mountains, gradually fading into the horizon. Filippo Brunelleschi formulated a linear perspective in the early 15th century. It helped create a sense of depth in paintings, making them look more realistic. This technique significantly shifted from medieval art, where backgrounds were often flat or filled with one color.

Leonardo took this technique further by studying how the human eye perceives distant objects, noticing that they appear less distinct and softer. To recreate this effect on painting, he invented a unique technique called sfumato (from the Italian word “sfumare,” meaning “to evaporate”). Instead of harsh lines, he applied thin layers of oil paint, blending tones and shadows seamlessly so that forms appear to dissolve naturally into the background. The technique created a soft, realistic transition between light and dark. The Mona Lisa has no harsh lines, and her face and landscape subtly fade behind, enhancing the painting’s depth and lifelike quality.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Mona Lisa is her enigmatic smile. Her expression seems to shift to many people depending on the angle and lighting. Looking directly at her lips, she appears neutral, but her smile seems broader and more alive when you look at her eyes or elsewhere. It is explained by Leonardo’s sfumato technique, where shadows and soft transitions make her expression ambiguous. Mona Lisa’s smile leaves interpretation open to the viewer’s emotions and perspective.

Who was Mona Lisa?

Mona Lisa was an Italian noblewoman, nee Lisa Gherardini, who married Francesco del Giocondo, a wealthy silk merchant. That’s why the painting is also called “La Gioconda,” derived from her husband’s surname. Francesco was the one to commission the portrait around 1503, likely to celebrate either their marriage or the birth of their second child.

However, some scholars believe Leonardo painted himself as a woman, noting similarities between the face of the Mona Lisa and his self-portraits. The theory is supported by Leonardo’s fascination with the balance of male and female traits. Thus, he created a portrait representing both genders in one.

Finally, a few experts speculate that the Mona Lisa could be an idealized, symbolic figure rather than a literal portrait of Lisa Gherardini. Infrared scans showed that Leonardo made multiple changes before the final one, meaning the Mona Lisa’s famous look was a later revision. Some believe the painting initially had eyebrows and eyelashes, which faded or were never finished.

In the end, the Giocondo family never received the painting. Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa for 16 years, continuously refining it but never considering it finished. He spent years perfecting her face, layering delicate brushstrokes to achieve the subtle, enigmatic smile.

The theories surrounding the woman’s identity, her shifting facial expression, and the discovered versions underneath add to the Mona Lisa’s timeless intrigue, making it one of the most studied and debated artworks in history.