Before answering when art was invented, let’s start from the basics. What is art? The answer to this question is surprisingly complex. However, the first thing that comes to mind is that humans made it all (at least all we know of).

In other words: wherever there is art, there are (or were) humans. So if we want to uncover the origins of art, we would need to dig into the roots of humanity itself. A compelling perspective, isn’t it?

If we only had a time machine! Well, to answer our question, let’s imagine we have it. Then, all we have to do is hop into it, push some buttons, and time-travel to… when?

Perhaps this is the most challenging question we have to answer here. Let’s explore our options.

Was there art before Homo sapiens?

Firstly, let’s limit our search to visual art. Unlike dance, music, and other performing activities, visual art has at least a tiny chance of surviving millennia. And if we’re to uncover the origins of art, we’ll have to travel back in time at least several dozen thousands of years.

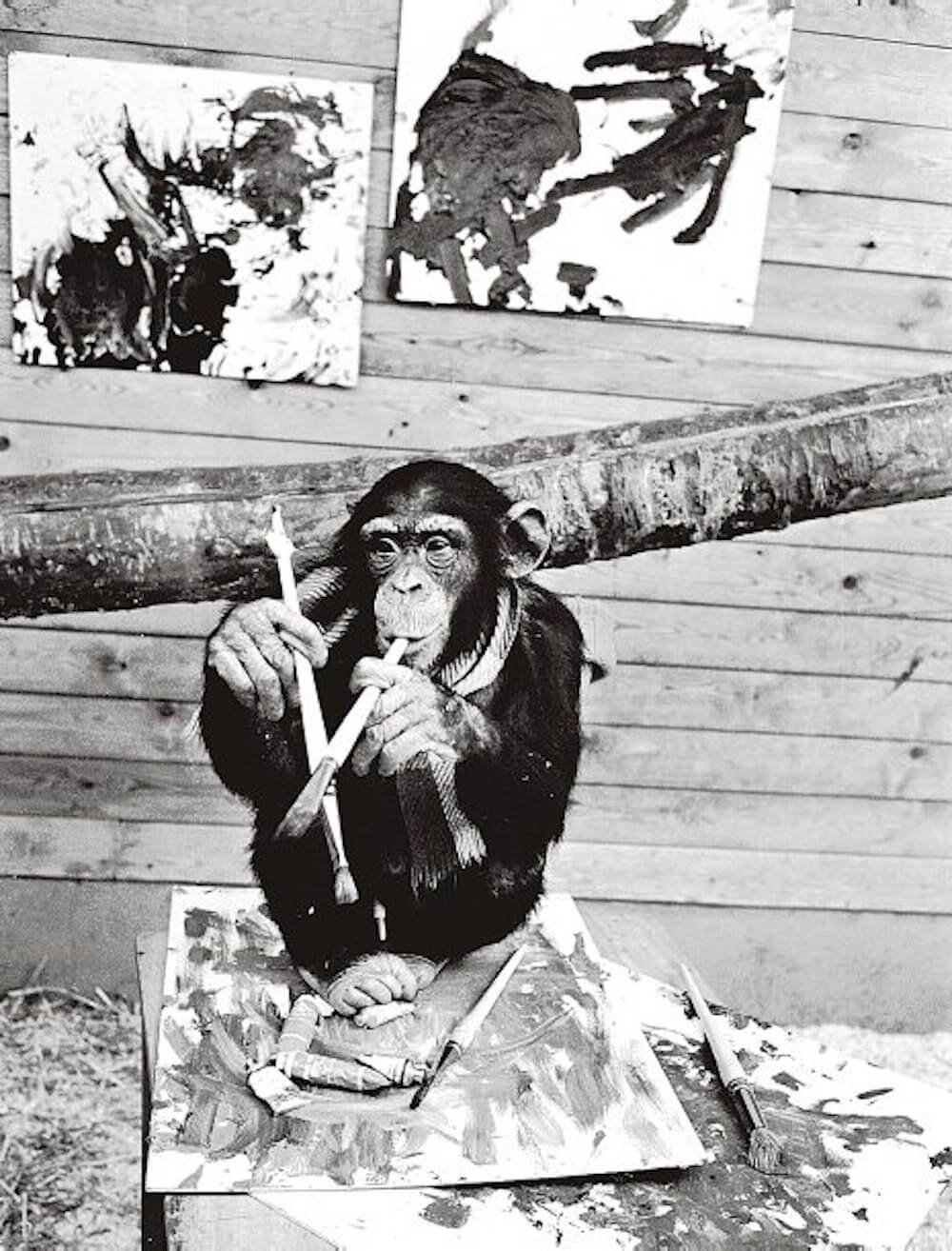

Secondly, should we limit our search to the emergence of Homo sapiens? Some researchers argue that the ability to enjoy colors and think creatively might even predate humans, pointing at the painting activities of some captive chimpanzees.

However, neither chimps nor any other (supposedly) highly intelligent animals have ever been spotted to paint in the wild—or, for that matter, do anything in the wild that would even remotely resemble painting. But at least we can assume that the last common ancestor between chimpanzees and us could appreciate colors.

If so, maybe some species on the long way between apes and humans could create full-fledged art?

There is no way to know it without a real time machine. Keep in mind: the deeper we go back in time, the fewer artifacts from that period have survived.

Also, it is unlikely that the first artists, whoever they were, created monumental projects—like cave paintings and sculptures—from the get-go. More probably, they began exploring their artistic side with body decorations: painting their skin and making simple jewelry.

And even when someone started creating art that is separate from their body, that art was probably made of small pieces of wood or other perishable materials. Unfortunately, to this day, we have no concrete examples of that—though there have been many fascinating and crucial discoveries of prehistoric art in recent years, so we may get lucky soon.

Many of those discoveries suggest that art was a defining feature of Homo sapiens—but not of any earlier species of Homo. However, there was one species that lived alongside us: our closest cousins, Neanderthals. The first Neanderthal remains were discovered in 1856, and the 19th-century science considered human evolution to be strictly linear. That’s why Neanderthals were thought to be our predecessors: and to this day, popular opinion depicts them mostly as primitive and brutish cavemen. The modern scientific view is that the two species were closely related, but humans didn’t descend directly from Neanderthals.

Early modern humans and Neanderthals coexisted for many thousands of years, quite often contacting and interbreeding (there is some genetic evidence to that).

Our neighbors apparently were quite intelligent species who knew how to use fire, cook food, and even bury their dead. Is it possible they made art as well?

Yes, there is evidence that Neanderthals at least decorated their bodies and made jewelry. However, science has long assumed that they started doing this only to mimic the behavior of Homo sapiens without understanding its symbolic meaning.

A discovery made in 2018 suggests a different possibility.

Let’s travel to our first time-machine destination: 64 800 years ago to the La Pasiega cave in the north of modern-day Spain. Painted red on a cave wall, several rows of dots go together in the shape of a letter S and something that looks very much like a ladder. The slightly visible animal shapes may have been added much later, but the ladder and the dots are at least 64 thousand years old. Impressive?

Here’s the plot twist: Homo sapiens would arrive in Europe only about 20 000 years later! That means Neanderthals were making at least nonfigurative (that is, abstract) cave paintings.

As for representative art (that is, depictions of real-life objects), it still looks like only early modern humans were doing it.

Scientists have long thought that early humans started making art quite suddenly: possibly thanks to rapid changes in thinking or behavior. It was suggested to happen soon after Homo sapiens migrated into Europe about 40 000 years ago (marking the start of the Upper Paleolithic period, also known as the Late Stone Age).

Indeed, the earliest figurative cave paintings and fertility sculptures date back to the same period and are already quite sophisticated and developed. And—for some unknown reason—most of them are located within modern-day Europe.

However, art could come to ancient humans not as a rapid flash of inspiration but rather in the form of a more prolonged and gradual evolution. Until the onset of the 21st century there haven’t been much archeological evidence to support the evolutionary model—but recent findings make it much more plausible.

Let’s jump into our time machine again: to Blombos Cave in South Africa about 70 000 years ago. We might meet a group of Homo sapiens doing rather pointless things (at least from a practical standpoint). These people are engraving ornaments on the pieces of red ochre (red ochre is basically clay, colored with iron oxide).

Over 8000 pieces of ochre were discovered in Blombos Cave, although only two seem to have been engraved intentionally. One of the pieces is quite intricate.

We see sets of lines crisscrossing into a kind of geometrical ornament—and unlike paintings in La Pasiega, they are symmetrical. Perhaps this ornament had a symbolic meaning, obviously requiring preparation, skill, and some form of explanation to the viewers. All of that is virtually impossible without a fully developed language.

This finding suggests that modern humans had started making art even before they migrated out of Africa and created the sophisticated and beautiful art of the Upper Paleolithic Period.

Earliest surviving examples: cave art

With the origin question sorted out, let’s dial some more coordinates into our time machine and review the beautiful examples of the earliest cave paintings we managed to uncover.

Leang Tedongnge, 45,500 years ago

There are several ancient Paleolithic Art sites in the karst caves of Indonesia, most of them discovered only recently. This one, reported only in January 2021, is the oldest known example of figurative art. Using the same red ochre that we already saw in Blombos, a prehistoric artist drew a quite recognizable wild pig in natural size. There are several other images of pigs (they did not survive this well), suggesting a scene of interaction between pigs, possibly a fight. There are also two stencils of human hands located near the pig’s buttocks. Perhaps, the viewers tried to cheer on the fighting pig? Later we’ll talk about the possible meaning of the hand stencils.

This pig proves that at the beginning of the Late Stone Age, humans created complicated figurative art not only in Europe but also on the opposite side of the world.

But consider this: obviously, there were no fighting pigs in front of the artist or artists in the cave. Back then, people didn’t know how to take photos—and even the techniques and technologies for quick sketching were out of their reach. So the only way accessible to them was to preserve the images in memory and draw them from their minds.

Chauvet, 33,000–30,000 years ago

This power of human imagination strikes even more from the earliest European figurative art in Chauvet cave, south of modern-day France. More than 420 animal images in that cave are reliably dated between 33 000 and 30 000 years ago. Unlike ochre-colored Indonesian paintings, the pictures of Chauvet come in various hues, mostly in black and red. The artists supposedly used many different techniques:

- Engraving

- Using pieces of charcoal as pencils

- Spraying the paints on the walls through tubes or directly from the mouth

They also cleaned the walls before painting them, showing signs of preparation. At the same time, they pioneered site-specific art by using the natural bumps and curves of the surface to enhance the artistic impression.

People usually think (and cave art of later periods somewhat supports this notion) that early humans depicted animals they hunted. However, this seems not to be the case here: there are bears, rhinoceros, and lions, which we began killing only much, much later and only for recreation. Animals look like they are moving and interacting with each other, just like real animals do.

Some compositions use spatial perspective, making them even more lifelike. Could all this mastery of shapes, lines, and colors result from a genius breakthrough? Maybe. However, a long tradition of honing skills and teaching from one generation to the next is much more likely.

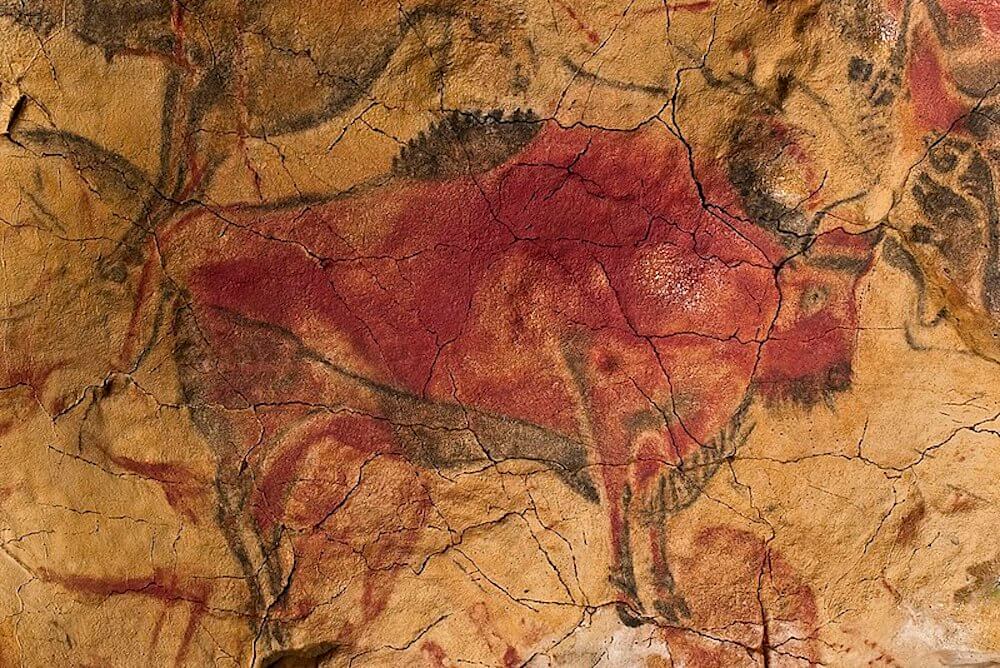

Altamira, 21,000–11,000 years ago

Paintings of Altamira in northern Spain were discovered by amateur archeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola in 1879. Conducting the excavations, Satuola hadn’t noticed the paintings for several months—until his 8-year-old daughter pointed at them.

Upon seeing the paintings, Sautuola instantly believed them to be the artworks of the Stone Age people. However, the 19th-century scientists simply couldn’t imagine such a level of skill and detail in brutish prehistoric cave dwellers. They labeled Satuola a fraud and attention-seeker—and he died before the scientific society admitted their mistake in the 1900s.

The Altamira cave was occupied (and painted) roughly 20,000 to 11,000 years ago. Here, just like in Chauvet, we see skilled animal paintings and engravings in red and black hues, often using natural wall reliefs to add volume and immersion. The animals are mostly horses, bison, and deer—not large predators, as in Chauvet. These images are often accompanied by hand stencils (and here they are again! Isn’t it peculiar?).

Lascaux, 17 000 years ago

The final one of the most renowned European trio of the Upper Paleolithic caves was discovered in 1940 by French teenagers looking for a dog who fell into a hole.

No sources bother to mention the fate of the pioneer dog, but we sincerely hope that it survived its famous fall. Still, it couldn’t see animal figures painted all around in the dark.

Numerous horses and less abundant bison, deer, aurochs, and even wild cats—all painted in red, black, and yellow hues approximately 17,000 years ago. The paints were possibly made of minerals from hundreds of kilometers away, or even obtained through trade. Whichever is the case, it shows the incredible dedication of the people of those times and the utmost importance with which they regarded the paintings.

Curious how humanity’s artistic journey evolved after cave paintings? Discover the symbolism in Picasso’s Guernica, the global fame of Mona Lisa, or explore the rise of modern pop culture through the colorful history of comics.

Can we visit these caves?

Unfortunately, no. The sad fate of Lascaux explains the reason.

Lascaux opened to the public in 1948 and soon became a popular tourist attraction—with a daily number of visitors averaging 1200. Unfortunately, in less than a decade, the paintings visibly deteriorated: mold and lichen covered the walls. Lascaux was closed in 1963 but has been suffering from mold infestations ever since. Altamira had opened for limited access in 1982, but it didn’t work out tremendously well either. As of today, it remains completely closed. Chauvet, discovered in 1994, has never been open to the public.

Thankfully, we still have beautiful photos and documentaries. In addition, people made several replicas of the caves: many pictures found online are actually photos of these replicas.

Curious how humanity’s artistic journey evolved after cave paintings? Discover the symbolism in Picasso’s Guernica, the global fame of Mona Lisa, or explore the rise of modern pop culture through the colorful history of comics. And don’t miss to learn how to know if painting is valuable.

Earliest surviving examples: sculptures

Not every piece of Paleolithic art that survives today occupies a cave wall. Whereas millennia ago, monumental cave paintings were à la mode in France and Spain, the artistic trend of Central Europe was female figurines.

Yes, we mean the famous ‘Venuses,’ although no one had heard about the Roman goddess of love back then. And contrary to popular beliefs, there is no evidence that these sculptures represented goddesses of love, beauty, and such.

Venus of Hohle Fels, 40,000–35,000 years ago

Discovered in Germany, it is probably the earliest figurine we know of—older than Chauvet paintings.

The sculpture is made of mammoth ivory and depicts a woman with big thighs, large stomach (engraved lines look very much like stretch marks), as well as significantly enlarged breasts and vulva.

In general, it looks like an exaggerated portrayal of a woman who’s recently given birth.

The figurine has no head—only a tiny perforated stump. Only 6 cm in height, it was most probably worn as a neck amulet.

Venus of Vestonice, 27,000 years ago

While still small (11 cm in height), this figurine discovered in the Czech Republic seems to be a bit large for a neck amulet. Dated about 27 000 years ago, it is considered the world’s oldest ceramic piece. It also possesses all the distinctive features of a fertility symbol: large breasts, suggesting long periods of breastfeeding, big thighs and belly, and little detail of the rest of the body.

There are no signs of it being worn on a string or put onto a pedestal: most probably, this Venus was designed to be held in hand. Maybe young women clutched it in their hands during their first labor, believing this symbol of a successful pregnancy and labor will help them and their babies.

Venus of Willendorf, 25,000 years ago

The most famous among Paleolithic Venuses, this one probably held the same function. Found in Lower Austria in 1908, this limestone sculpture is about 25 000 years old. It has the same height as Venus of Vestonice—11 cm; but it looks less stylized and more life-like.

While the face is still absent, the head is full-sized and covered with a pattern, possibly representing braids or a cap. Could it be a depiction of a real woman? We will never know for sure.

More interestingly, some researchers suggested that a real woman created Venus of Willendorf (as well as other Venus figurines). The seemingly exaggerated body proportions represent a female body from the point of view of a woman who looks down on herself.

It could be a fun experience for a modern-day woman: take a piece of modeling clay, undress, look down on yourself, try to recreate what you see, and then compare it to what your extremely distant ancestors made.

Whether the suggestion is valid or not, it definitely would be wrong to assume that only males created Paleolithic art!

How was art invented?

Was all of this made possible by our development as a species—when our brains grew more prominent and fingers became more nimble? Had it been the only explanation, we would have probably found art that dates back to the emergence of Homo sapiens as a species roughly 300,000 years ago. We already know that this is not the case.

To explain this fact, scientists distinguish the anatomically modern human from the behaviorally modern human. The latter supposedly shares more features with what we are today.

One of such features is the capability for advanced planning. And we humans can get very advanced with it—all of us have this unbelievably gifted friend who has their life planned for years ahead, right? The second feature is the ability to communicate in symbols.

To make art, we need to plan ahead; art is symbolic. So, these features are crucial to create art. There are other necessary components of making art, all interconnected. We’ll take a deeper look at two of them: language and ritual.

All human societies use language, whereas no animal has ever developed it—just like art. We may interpret some forms of animal signaling (think singing birds) as language, but any proper language needs grammar, vocabulary, and arbitrary conventions.

To explain the bit about arbitrary conventions in simple words: there is nothing in how the letters of the word “cat” sound that would suggest their connection with this particular animal. We simply learned to assign this specific meaning to the word, and we have a mental image of a cat linked to it. This is a pretty advanced stuff only a human brain can do.

When did we acquire this ability? Some researchers estimate that language first evolved in Africa about 150,000–100,000 years ago. Others argue that language started to develop much more rapidly about 70,000 years ago after one mutation had allowed humans to consciously synthesize mental images of non-present objects.

Our brain develops many new neural connections by using language, allowing more complex symbolic behavior needed to create art. At the same time, making and explaining art encourages communication and the creation of symbols, helping language evolve further.

What’s more, it is suggested that this double development of language and art, for the most part, happened within the context of rituals.

When was art invented?

And so, our time-machine journey has finished. While this is the type of journey that is probably more valuable and fascinating than the destination—we have started with some questions in mind. Did we find the answers?

Well, to a certain degree, yes. Seventy thousand years ago seems to be the most plausible date for the earliest visual art. And it probably was created in Africa.

But even before the first image was carved or painted, art had already existed in the human mind.