Ancient Rome: a birds-eye view on the empire, its history, and legacy

Popular culture has a bit of a thing for Ancient Rome. It is certainly amusing, but what is the reason? We created this course to tell you more.

We get to hear a lot about Ancient Rome from popular culture. It often comes down to some brief (and, mostly, incorrect) facts from the HBO series Rome, the Gladiator film by Ridley Scott, and the French comedy Asterix and Obelix vs. Caesar.

It’s certainly amusing that popular culture has a thing on Ancient Rome, so we created this course to tell you more (and the truth).

Why was Ancient Rome so important?

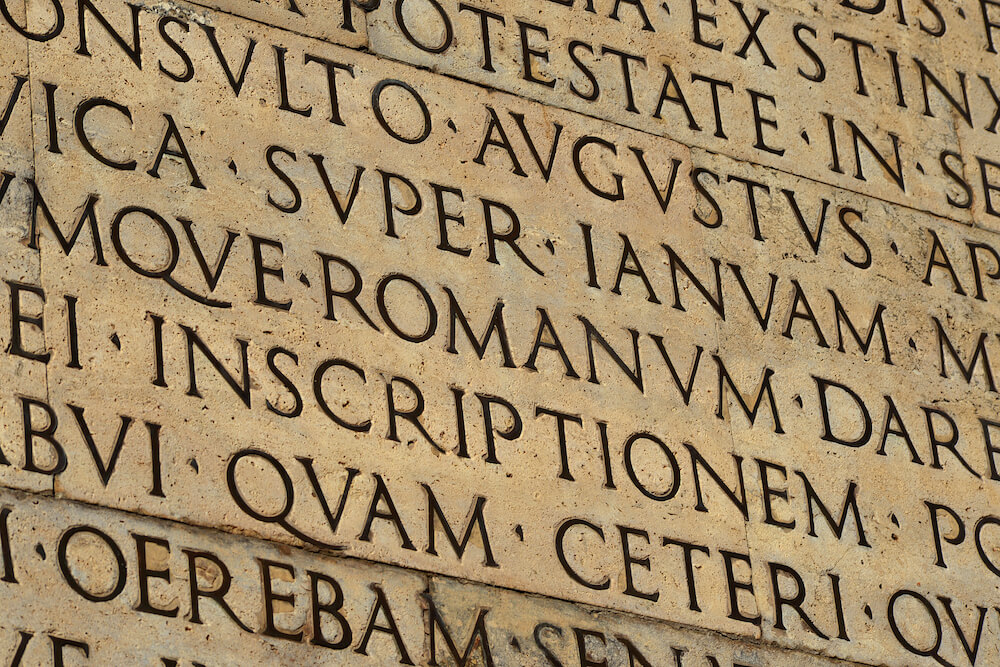

Right now, you are reading this text written in Latin letters, the letters invented by Romans for use in the Latin language. They use Latin letters not just for English, German, and Italian, but also to write down other European, African, and Asian languages from Vietnamese, Afrikaans, and Indonesian to Maori and Swahili. Besides, a good half of the world speaks the Romance languages as their first or second language, and those are direct descendants of the Latin language spoken in Ancient Rome.

Most cultures use the calendar and time measurements that are largely based on the Roman ones.

Romans gave us instructions on building cities, roads, and things like domes, viaducts, and even sewers.

Government institutions in France, Italy, the USA, Germany, Mexico, and many other countries derive a lot from the Roman political system, as did dictators of the past, from Benito Mussolini to Adolf Hitler, who sought inspiration for their projects in the dark, belligerent pages of Roman history. Even the Star Wars conflict between the Jedis, Palpatine, and the Senate of the Galaxy tells a loose short story of a crucial period in ancient Rome—a transit from the democratic republic to the autocratic empire.

Last but not least, due to the Roman Empire wars, quite a few European capitals and business spots sprung to life—London, Paris, Cologne, Vienna, and others.

So, let’s explore the history of Ancient Rome to understand how we came to the ways we measure time, elect politicians, have holidays, and decide on the goals of human progress.

From the dawn of civilization to the city of a million

We have to go back as far as the 8th century BCE. The ancient civilizations of Egypt and Babylon are slowly falling into decay, while the Greeks are certainly on the rise, creating hundreds of colonies across the whole Mediterranean region.

In the north of the Italian peninsula lies vibrant and mysterious Etruscan civilization, in the south—prosperous Greek city-colonies. The village of Rome is situated right in between, in the region called Latium. As Etruscans and Greeks committed their trade operations and wars, many outlaws, runaway slaves, and poor farmers came off the roads to live in this shabby place on the banks of the Tiber river. This village was specked on seven hills divided by moorlands.

It doesn’t sound anything like the origin of the pompous and honorific Roman civilization, does it? That’s why Romans suggested their version of the events, and later, the ancient poet Virgil added details and artistic delicacy to this legend.

When the legendary Trojan War took place, as Homer tells it, around 1200 BCE, many people had to leave the desolated land and find a home elsewhere. One of them was a cunning aristocrat Aeneas, who found ships and fit-and-lean Trojans to accompany him on his trip to a new homeland. Through many years and adventures, they sailed to the banks of Italy, somewhere close to modern Rome. The indigenous tribe of Latins tried to throw the newcomers back, but Trojans defeated Latins and took their name.

In hundreds of years, Aeneas’ descendants, twin brothers Remus and Romulus, were ordered by the Latin king to be thrown to the Tiber to die. Instead, according to the legend, the Roman god Tiberinus saved them and brought them to a she-wolf. For some time, the wolf nourished and took care of them before a shepherd found the twins and took them home.

When Romulus and Remus grew up, they tried to take revenge on the Latins who tried to kill them. Coming to a site of modern Rome, they wanted to found a new city whence they could commence a war against Latins. Instead, in a nasty feud, Romulus killed his brother Remus. He founded a new city on his own in 753 BCE and named it likewise—Rome (Roma in Latin). The legendary version fits the grandeur of Ancient Rome better, doesn’t it?

After Romulus, there were six more half-legendary kings. According to legends, each gave something valuable to Ancient Romans: alphabet, numbers, calendar, and a temple to the chief god, Jupiter. Historians, however, claim that Romans just adapted or plagiarised the Etruscan inventions. It is obvious in the case of the alphabet. Etruscans created their letters from the Greek alphabet. The Latin alphabet popped out much later as a modification on Etruscan writing. Roman legends and history, though, depict Etruscans as a tribe of poor barbarians that tried to conquer Rome.

As Romans were at war with the Etruscans, the kings were losing their reins. Around 509 BCE, a sexual scandal brought Roman kings down. A king’s son, Sextus Tarquinius, out of sheer spite, raped a renowned nobleman’s wife, Lucretia. In turn, the Roman populace revolted, overthrew, and exiled the last kings of Rome.

It was the beginning of the Roman republic. The fathers (patres in Latin) of the 300 oldest founder-families of Rome got together to form a new government—Senate.

They elected two consuls each year to enforce laws and decisions that the Senate delivered. They were the patricians—the aristocracy of a new republic. Families that weren’t considered old or famous enough became plebeians. Originally, the plebs couldn’t affect policy-making by any means.

Until about 300 BCE, the Roman republic was mostly enmeshed in struggles between patricians and plebeians to balance power. Plebeians made up the bulkiest part of the army despite being deprived of political power. As neighbors constantly assaulted the young state, plebeians teased and bullied the senators that they would leave patricians alone in the face of enemy forces and evade fighting. Gradually, patricians gave in to plebeians’ demands, creating an office of a plebeian tribune who could veto law-making if he considered it inconsistent with the interests of the plebs.

In 287 BCE, plebeians managed to pass a written codex of laws that equaled them with the patricians. They put this new philosophy of social unity into a Latin phrase Senatus Populusque Romanus or S.P.Q.R., meaning “The Senate and the People of Rome.” It was on the coins, documents, and public buildings reminding that Romans would stand together and fall if divided and clashed with each other. They called it res publica —the common affair.

All the while, many surrounding tribes, and nations attempted to conquer a newly-born republic. In the heat of conflict between patricians and plebeians in 390 BCE, Gauls came from the north, invading and almost destroying the city at night. Watchdogs were sleeping tight and didn’t signal the enemy coming, but, unexpectedly, geese did. Since the invaders managed to sack the city badly, Romans established a tradition to crucify dogs every year as a symbolic punishment for their misdemeanor. The geese were dressed in gold and jewelry and led on military parades.

Romans realized they needed a military reform and built a defensive wall around the city to prevent any such future sacks. As they build city walls for defense, they started attacking others and conquering the Italian peninsula.

Over a hundred years, Pyrrhus of Epirus, one of the smartest generals of the ancient world, tried to help Greek cities to defeat advancing Roman forces. In a crucial battle, Pyrrhus formally won over, but Romans brought huge losses on his army. Despite Pyrrhus achieved tactical victory, it made no sense as the army shrank to a minimum. An idiom “Pyrrhic victory” has its roots in this event.

When the Roman republic reached Sicily, they came in contact with another powerful foe, the empire of Carthage. Romans called them Punes and these wars were called Punic. From 264 to 146 BCE, they had three fits of lasting wars to bring each other to total destruction. During the Second Punic War, Hannibal, general of Carthage, marched from Africa through Spain, southern France, over the Alps to Italy. Romans were amazed at the speed his army covered this distance but Hannibal wanted to surprise them with an army of elephants that could stamp down and crash Roman warriors on the battlefield. Unfortunately, most elephants died from extreme cold and harsh conditions in the Alps mountains.

The Romans won the wars, even twice. In the Second Punic War, they annexed Spain from the Carthaginian empire and ordered it to demolish the Carthage city walls. In the Third (final) one, in 146 BCE, they put the city on fire, killed everyone, and sowed the land with salt to make it desolated forever.

In the same year, Roman armies conquered remnants of Alexander’s empire, destroying another ancient city—Corinth. Now the Roman borders stretched from modern Valencia and Gibraltar to Athens and Istanbul. Rome became a large city with people from different walks of life and origin. According to the Roman census, about 400 000 male citizens lived in the city at the time. With women, children, migrants, and slaves added, historians argue it could have reached 1 million citizens.