Design: How Bauhaus influenced everything?

Bauhaus is one of the most influential movements in the history of design and architecture. Discover its story, the main principles, and the most prominent examples.

Introduction. A brief encounter with Bauhaus

Bauhaus in German means a house of construction. It is the name of the art school founded by German architect Walter Gropius in 1919 in Weimar.

This school gathered prominent artists together: Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer, Johannes Itten made their impact on Bauhaus theory, and practice.

In 1925, Bauhaus moved to a building designed by Gropius in Dessau. Now, there is Bauhaus Dessau Foundation that preserves the Bauhaus heritage. The building itself is on UNESCO World Heritage List.

In 1932, the Bauhaus school moved to Berlin, but in 1933 it had to close down under the pressure of the Nazi government: it was declared “un-German” and “degenerate art.”

Some of the school members have not survived World War II, and others fled the country, spreading the ideas of Bauhaus worldwide.

Walter Gropius taught in Harvard Graduate School of Design; László Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe became the head of the Department of Architecture of the Armour Institute in Chicago.

Despite the short history of 14 years, Bauhaus became very influential. Every day, we see plenty of things that took their looks from Bauhaus designs: table lamps, watches, chairs, clocks at train stations, iPods, cars, etc.

We can reduce the main principle of Bauhaus to one word: practicality. Every Bauhaus design should be utilitarian with minimal decorations. Bauhaus designer chooses materials with consideration of mass production in the future.

Bauhaus Revolution: Why it made a difference?

After the First World War, Germany was in crisis, both economic and existential. Walter Gropius, 35, a war veteran, tried to get an architecture job in shattered Berlin. His career was interrupted by war.

During 1908-1910, he worked with architects Peter Behrens and Adolf Meyer. Together with the latter, he designed the Fagus shoe factory, one of the most prominent examples of early architectural modernism.

The career of Walter Gropius resumed fully in the Weimar Republic, established in 1918 and associated with a thriving cultural life.

In 1919, Gropius was appointed as a master of the Academy of Fine Arts. He proposed to establish an architecture department and give the school a new name—Bauhaus.

That year Walter Gropius published his manifesto with the main principles of the renewed school.

“Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come,” he wrote.

The Bauhaus Manifesto was not pure theory. Gropius embedded it into the way people learned at Bauhaus art school.

For years, people called for reforming the art education in Germany, and Gropius managed to bring the necessary changes to life.

Bauhaus taught its students to be artists and artisans at the same time. All students studied the fundamentals of color and form and were encouraged to experiment with materials and media.

Studying at Bauhaus meant that a student became an apprentice at workshops and mastered the craft. Gropius considered it would overcome the results of industrialism where machines did all the hard work.

The broad field for experiments, teachers, and artistic environment led to producing some iconic designs. In 1923, for example, Bauhaus student Wilhelm Wagenfeld created a lamp that became well-known and later mass-produced and sold in Germany then.

As for other recognizable Bauhaus objects, here is the iconic table clock designed by Marianne Brandt.

Brandt was the only woman who got a degree in metal works in Bauhaus, a division dominated by men. She worked at Ruppel company that specialized in mass-produced metalware. The table clock she designed went into production in 1932 did not have a glass covering on its clockface and was made in black metal and chrome. All in all, it embodied a pure function.

What about Bauhaus teachers?

Paul Klee was a prominent German artist whom Gropius invited to Bauhaus in 1920. He taught the course about Form, Drawing, and Design that was preliminary. His books on foundations of design and art theory were published in the 1920s and impacted further generations of artists and designers.

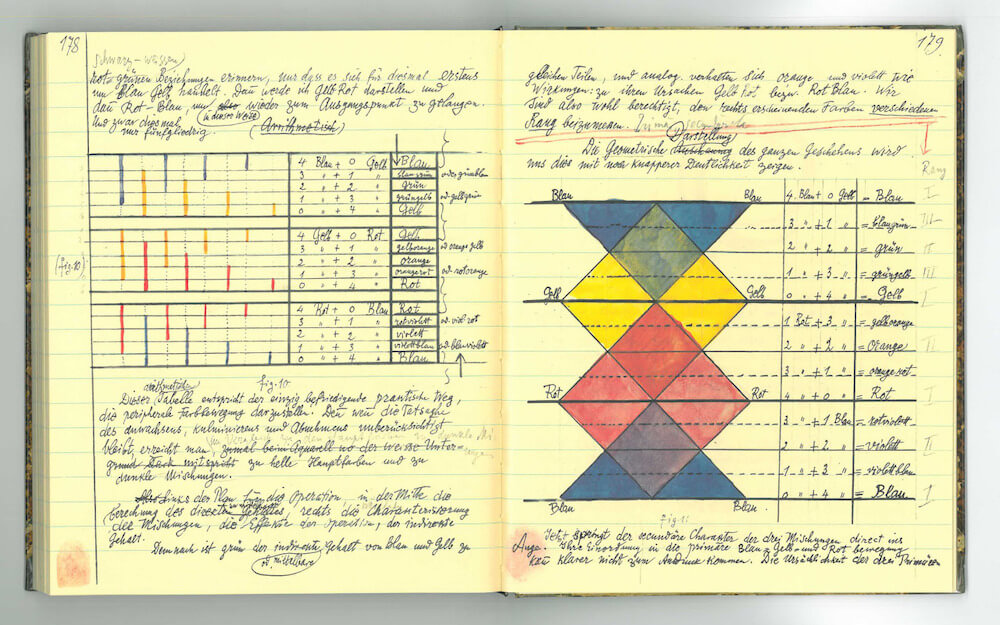

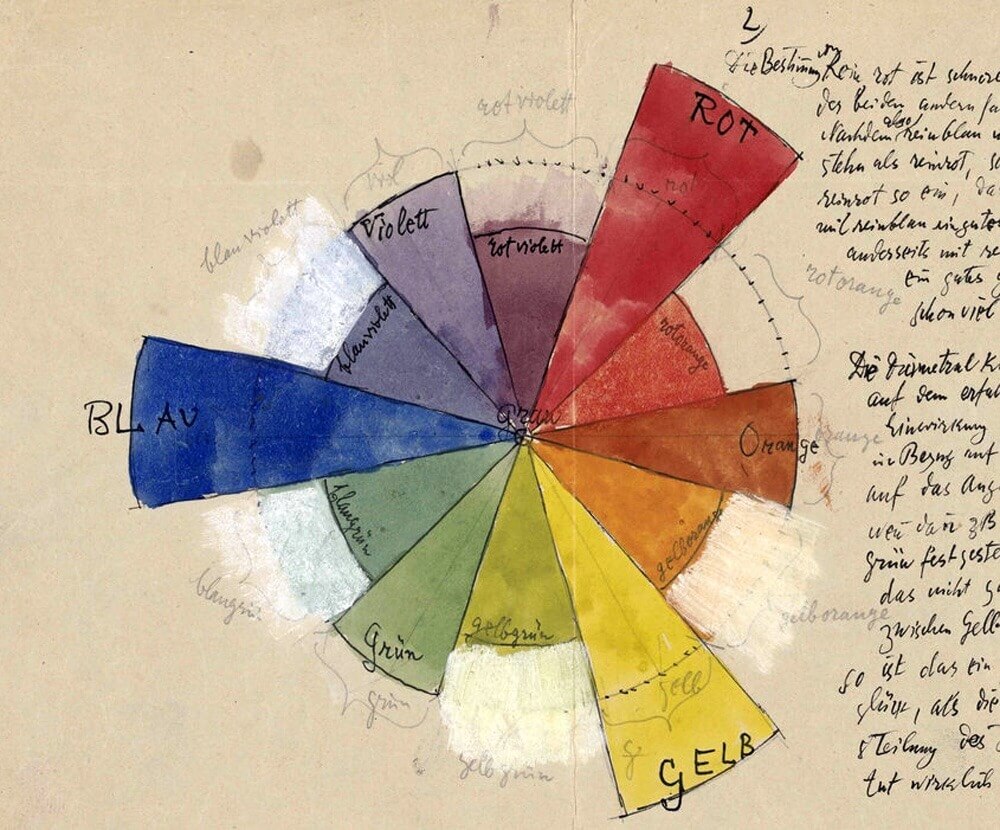

His influential color theory was based on dynamic transitions of complementary colors and inspired by music theory.

Swiss expressionist painter and color theorist Johannes Itten was the author of the famous Preliminary Course that was obligatory for all students starting at Bauhaus. The course provided the necessary introduction and taught students the basics of material characteristics, composition, and color.

Itten developed the theory on seven types of color contrasts. His work influenced abstract artistic movements, Op Art, and even the cosmetics industry.

After Itten’s departure from Bauhaus, Wassily Kandinsky joined Bauhaus as a master. He was already a famous artist and taught a wall painting workshop, abstract form elements, and analytical drawing.

He emphasized the importance of dynamics between shapes and colors and created a color-form classification system. Later, he taught a theoretical course on creative design that involved studying the relationships between art, architecture, and technology crucial for Bauhaus.

To sum up, the recipe for timelessness and influence of Bauhaus is simple. It was a vital place for eager people to study and embody the principles Walter Gropius and his colleagues shared.

Almost 200 students studied at Bauhaus from 1919 till 1933 and became artists and architects; furniture, typeface, industrial, and graphic designers; printmakers, illustrators, and educators in their fields. When the school was closed down, they went abroad and made Bauhaus a global phenomenon.