Human mind: what’s going on inside your head?

Mind is a mind-boggling thing: all human curiosity, intelligence, knowledge, and creativity start there. So let’s honor the very thing that sets humans apart from other animals.

The mind-body problem

Have you ever wondered what is going on inside your head? Well, there’s a bunch of nerves, ganglia, neurons, and synapses that exchange various signals to make us react to the environment and move around.

But what does it really mean to think? To be happy? To remember something? To be intelligent? We have a word that refers to all of these abilities and more: the mind.

You are probably aware that certain brain regions are in charge of different processes related to decision-making, emotions, and instincts. Course block

For example, the left and right frontal lobes govern many crucial aspects of personality. There was a very famous case that highlighted this particular connection to neuroscientists, psychologists, and philosophers.

Phineas Gage was a young railroad construction worker in the 19th century who survived a freak accident. An iron rod went through his left cheek into the brain, leaving through the top of the skull and almost destroying the left frontal lobe of his brain. Before the accident, people spoke of him as a healthy, active, intelligent, and responsible person.

Gage lived for 12 more years after that. His brain recovered: he did not lose his abilities to speak, hear, or move.

However, his friends and employers noticed many changes to his personality: they reported that he became “fitful and irreverent,” “indulging in the grossest profanity,” “impatient and capricious.” Some went as far as to say that he was “no longer Gage.”

Later studies suggested that some of these changes may have been temporary—and part of his social functions had also recovered over the years. Nevertheless, the case of Phineas Gage shows us that personality (which is something non-physical) can be affected by changes in the physical body.

The debate whether non-physical aspects of a human being—mind, consciousness, and personality—are in any way related to our physical bodies is a long and ancient one. It is known as the mind-body problem. It goes like this:

Do we, humans, have something that is separate from the body (called mind, or spirit, or soul, or something else) that controls the body or is being controlled by it?

Throughout history, there have been many attempts to answer this question.

The most straightforward answer is to reduce everything to the physical matter the world is made of. This approach, known as reductive physicalism, explains every aspect of the mind in terms of neurons, hormones, and neurotransmitters. It is the logic by which doctors prescribe medication to change the chemistry of neuron interaction—and through it affect the behavior.

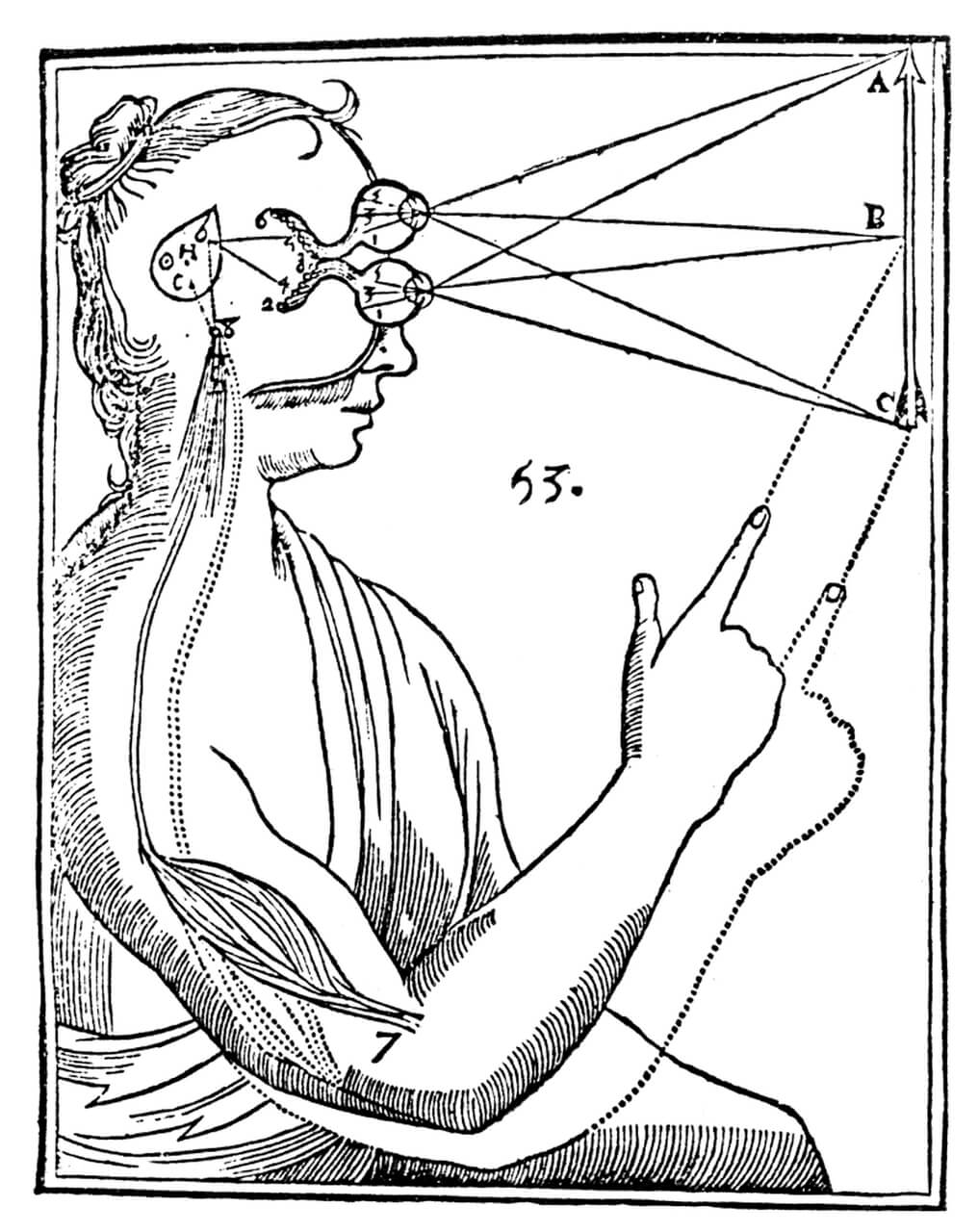

A French philosopher of the 17th century René Descartes, the author of the famous phrase “I think therefore I am,” was sure that an immaterial mind exists parallel to the material body: that is, mind and body exist as two different substances. His approach is known as substance dualism.

Descartes was also positive that the mind is contained in a small region of the brain known as the pineal gland, which he described as “the seat of the soul.” He believed it to be a unique organ to humans, which provides us with an ability to communicate with the “rational soul.” However, today it is considered just a normal brain gland among many. Animals also have it. Its primary responsibility is producing melatonin—the hormone which regulates sleep.

Another theory exists as a kind of compromise between the two previous ones. Consider this:

- Our mind (thoughts and feelings that we cannot touch, see, or in other ways express as material objects) can control the body and make it do what we want.

- And yet, the physical state of the body and the environment influences the mind.

In other words, humans and other creatures combine both physical and mental properties. The mind and the body interact with each other, hence the name of the theory—interactionism.

For instance, you can take your body for a run in the morning, even though the weather is cold and the bed is so cozy and warm: this is how your mind influences your body.

And the next night, you stay out late, binge-watching a new season of a TV show, probably regretting it the morning after: this is how your body influences your mind.

There’s a lot of debate about instincts and whether they are something that humans have. Instincts are generally thought to be the property of animals. Humans do have some: for example, the desire to hold a newborn baby in their arms, even if the baby isn’t theirs, is a manifestation of an instinct. But the critical difference between humans and other animals is that we can overcome instinctive behavior and control it.

Consciousness: being aware

However, let the mind-body problem concern philosophers. There is probably no scientific answer to it because the human mind is highly subjective.

Each of us perceives things in their unique way. It is impossible to tell if the other person sees the red color, feels an ocean’s breeze, and tastes an apple the same way you do. These unique experiences—things we see, hear, and feel in our own way—are called qualia.

Qualia start with our mind’s ability to perceive sensory information. After receiving the information from sensory organs, our brain interprets and organizes it to make a complete image of reality around us.

Neuroscientists calculated that the brain processes about 11 million bits of sensory information per second. Imagine yourself at a party with loud music, stroboscopic lights, many people around, noises, smells, touches… Yet when a friend calls your name, you instantly hear it.

This ability is called selective attention. Our mind can focus our conscious attention on a particular stimulus. It works like a spotlight that puts one thing in the center and darkens the other stuff. In other words, consciousness allows us to direct our attention.

The consciousness and the mind are related concepts—although not entirely the same thing. Being conscious means being aware of yourself, your feelings, thoughts, sensations, memories, and environment.

Like qualia, each one’s consciousness is subjective and unique. But you can describe almost any experience by words—it is also a part of your consciousness.

One of the defining features of the human mind is the ability to produce and understand language.

Language is the way of communication—it includes speech, gestures, and writing. It starts to develop at an early age. To speak to each other, humans need certain brain regions, ears, vocal tracts—but most importantly, social interaction. The two regions where all the language-related magic happens are Broca’s area (located in the frontal lobe of the left hemisphere) and Wernicke’s area (in the left temporal lobe). They analyze the incoming audio data to distinguish words and give out commands to vocal tracts, producing speech.

The critical age for language development is the age of 1.5–3 years. A child not taught to speak at this age, without any experience of social interaction, will probably never be able to speak or understand human speech.

To learn from our experience and know the meaning of words, we need to remember things. The role of memory is to encode and store information to be retrieved when needed. Several brain regions are involved in the process simultaneously—mainly the hippocampus and the temporal lobes.

Memory can be short-term or long-term: keeping in mind things we just experienced or recalling something from long ago. Forgetting is a crucial ability as well: it protects the system from overloading and frees up the space for new information.

There is a famous case of Solomon Shereshevsky—a Soviet journalist able to memorize loads of information and recall it through the years. His case was described in the book The Mind of a Mnemonist by Soviet scientist Aleksandr Luria.

Solomon developed several mnemonic techniques to help him remember things through associations. He used his ability to take part in performances and scientific experiments. There are other people in the world diagnosed with hyperthymesia—they are just unable to forget anything they experienced. Have you ever noticed how a strong smell can bring about specific memories? This phenomenon is not as rare as you might think—the olfactory nerve (the one responsible for delivering the information from the smell receptors) lies near the hippocampus, where the memories are consolidated. That way, a smell can “build itself” into a memory.

Memory is a fascinating thing. Many brain regions are working together to help you remember and recall loads of information before an important exam—and forget the moment it is over.

Cognition: thinking

Being aware is an essential feature of the mind—but when asked what the mind does, many people would point at another ability: thinking.

Remember Descartes with his famous “I think therefore I am”? No other words point out the importance of thinking better. Thinking—or, more scientifically, cognition—is a mental process of gaining knowledge and understanding of the world.

Cognition happens through thoughts, experiences, and senses. It involves attention, memory, language comprehension, knowledge, reasoning, judging, problem-solving, and decision making.

Cognition works by creating concepts—abstract groups of similar objects, events, people, or ideas. Concepts band together into prototypes, which are mental images of particular things. Concepts and prototypes allow us to think fast and save processing time—but they also lead to misjudgment when we are faced with something “out of the box.”

Concepts also help us communicate and understand each other. When a friend asks you to hand them an apple, you probably know which action they want from you and which object they refer to.

Prototypes and concepts can change, expand, or transform. For example, 50 years ago, the concept of a phone probably looked like this for many people:

And now most of us imagine a phone like this:

We use cognition to solve problems and make decisions. We do it all the time: for instance, finding our way home every day or choosing what to cook for dinner. Depending on the problem, we approach problem-solving in different ways: sometimes we go for accuracy, at other times speed is appreciated.

Problem-solving and decision-making are quite exhausting for the brain—that’s why we also tend to simplify repeatable and routine things by following logical algorithms (they are also called heuristics).

Heuristics are simple strategies that allow us to speed up a decision. However, sometimes the decision turns out not as accurate as when following the complete logical path. Heuristics are often connected to our intuition.

Advertising and marketing make use of heuristics to attract customers. For instance, if there is a choice between the cheapest, medium-cost, and expensive product, the customer will probably go the middle option, paying less attention to other properties of the product. Other animals also show evidence of cognitive abilities. Gorillas can plan, crows can use tools, and elephants can teach each other. Some species of birds (especially the migrating ones) have well-developed spatial memory.