Is communism possible in today’s world?

People have made attempts to build communism for nearly two centuries. If it promises a utopia, what holds us back from creating it?

When did it all start?

What does the word “communism” invoke in our minds?

Some of us have read the Communist Manifesto studying at high school or university. Some remember the Berlin Wall or the USSR. Many of you can recall that China’s only ruling party is a Communist Party. There are hundreds of possible answers to what communism is all about, and some contradict each other.

So, instead of focusing on the boring theory, let’s look at it from a practical standpoint. Can people efficiently establish a communist society today? What has been standing in the way of building a communist future for all humanity?

The world has changed much since Karl Marx published the Communist Manifesto in 1848 and Das Kapital in the latter half of the 19th century. Here we’ll explore how communism could fit in today, socially and economically.

Truth to be told, people voiced ideas that could be deemed communist long before Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. For example, Plato was among the first to described some version of a “communist” society in his much-read Republic that dates back to the 4th century BCE.

We can find even more nuanced and fine descriptions of a “communist” society in Thomas More’s Utopia and Tomazzo Campanella’s The City of the Sun. These two 16th-century philosophers described communities with no property, no money, no religion, no greed, no crimes, and universal love between all people. Pretty much like in John Lennon’s Imagine, right?

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were the principal theorists of communism, combining theories of sociology, economics, and psychology to create a concept of advancing humanity to a next stage. Their prime concern was with the mode of production—how people divide power and work in society to survive. In their view, social progress runs, roughly speaking, from “cruel” modes of production to more “humane” ones.

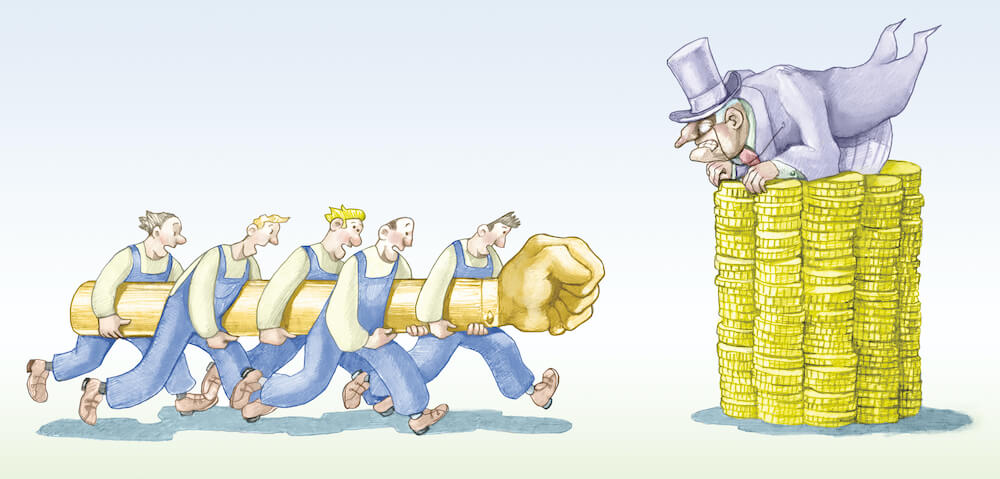

According to Marx, we’d lived in a “slavery mode of production” where most people were slaves and worked for their masters without any payment, getting only food and shelter. In feudalism, most people were serfs and had to give some part of what they produced to a lord. Now we live in a capitalist society where a small class of people own means of production and pay some wages to workers who do productive jobs. Controlling the access to factories, natural resources, and transportation, these few are the only ones to decide how much their workers receive.

Marx and Engels saw the injustice in that the workers do “real jobs,” whereas the capitalists live off the profits of their work. To fix the society, according to them, the access to means of production should become collective.

In a nutshell, communism seeks to justly divide the benefits what people produce between everyone. As long as selected individuals own the means of production, only few get richer, and the majority spends their lives in never-ending “wage slavery.”

What’s so unique about communism?

As Karl Marx explained, capitalism has its pros and cons. Competition between businesses for customers and resources had facilitated most of the scientific and technological advances we have now: trains, medicine, infrastructure, computers, etc. However, there are limits to making profits out of everything. Thus, business owners will face a challenge one day: workers will get more expertise and experience, demanding higher pay, but the cycles of booms and depressions of the capitalist economy will drive profits down.

Marx foresaw that educated workers would realize their power to sustain the whole system, appropriate (that is, take for themselves) the means of production, and impose effective control over everything else. It should be the end of capitalism.

However, Marx also admitted that no transition period between two conflicting modes of production can be smooth, quick, and short. It might be peaceful—with workers electing people who would establish communism—or quite blood-shedding if capitalists wouldn’t give in. But it will, undoubtedly, take some time until people establish collective ownership.

The point is that Karl Marx didn’t provide a universal scenario for this transition. He suggested that before communism takes root, there will be socialism. In socialism, the state acts as the primary employer and universal planner. It owns the means of production, gives people what they need, plans who works where, and distributes the goods in economics. And, well, makes final preparations for the onset of the communist utopia.

But why can’t we jump straight to communism without waiting in socialism limbo?

Communism necessarily implies:

- No state and no government

- Only collective ownership, not state ownership

- No money and no markets

- Everyone gets as much as they need and works as much as they can

We can see that jumping from economics that operates through money, private property, and free market to the one with collective ownership can be too bumpy. That’s why the transition was supposed to be going through socialism and state ownership.

So, now you should know the distinction between socialism and communism. Before we go on, consider this important side note: every communist program is necessarily a socialist one; not every socialist program envisions communism.

What stood in the way of communism in the past?

Marx died in 1888, but communism still hasn’t happened in 2021, as we’re writing this. Why?

Some Marxists thought that Marx was “too soft.” Why sit and wait for the advent of communism? Working people have to resist capitalism actively; they should bring about the changes with revolution—and, if necessary, terror. One of the people to go by this logic (and, arguably, get the most success with his methods) was Vladimir Lenin.

Many “revolutionary Marxists” started up a bunch of revolutions “for the people, for the workers, for the communism” in their countries. The most famous one was the Russian revolution of 1917—the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics existed from 1922 through 1991.