Plan С in case of apocalypse: Svalbard Global Seed Vault

As humanity contemplates the threat of a global catastrophe, we mainly think about prevention. However, some projects are created as a contingency. Let’s discuss one.

The largest collection for humanity’s benefit

For many, collecting was a childhood hobby; for some, it’s a lifelong passion. Extensive private collections can contain dozens or even hundreds of thousands of thematic items. For example, a lady in Wisconsin holds 11 000 Smurf-related memorabilia, and one person in the Czech Republic has 200 000 bus tickets.

People like accumulating similar things: they tell us about memories, childhood, hobbies, or visual examples of our past. However, these items have little to no practical usage most of the time… except when it comes to scientists who collect things for the sake of all of humanity.

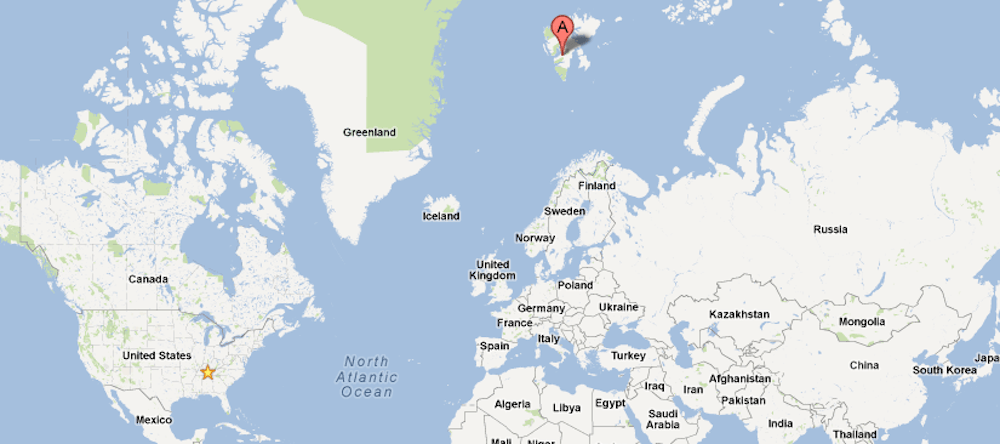

There is a bunker that stores millions of seeds from every part of the world. It is dug into a mountain on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, part of the Svalbard archipelago halfway between the northern coast of Norway and the North pole.

It is called the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, and it’s our backup plan in case there is something wrong with the ecosystem. In other words: in case of a global disaster. Scientists estimate that approximately 400 000 plant species exist today. Alarmingly, a large part of them—from 25 to nearly 40 percent—face the risk of extinction due to rapid climate change.

By 2022, the world’s countries have donated over a million samples of distinct crops and varieties to the Vault (note that one species can have many cultivated crops). In an ecological emergency, the seeds can be withdrawn and replanted.

It already happened in 2015: Syria withdrew some of its donations to replace what was damaged during the war.

Obviously, climate change and wars (be they global or local) are not the only contingencies the Vault is prepared for. For instance, some places constantly face the risk of natural catastrophes: volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, or earthquakes. All this inevitably affects the vegetation diversity. Volcanic soil is rich in minerals, so the plants can make a big comeback when the lava cools down. On average, it takes from 2 to 10 years for plants to completely regrow after the eruption.

Apart from that, plant diseases or insects might kill a whole plant population, especially if it is artificially cultivated. For example, the “Gros Michel” variety of bananas was almost wiped out in the 1950s.

There are chemicals to cope with such problems, but they are not universal. Firstly, they can cause further long-term damage to biodiversity; secondly, new diseases appear all the time, and it takes time to develop an antidote.

This makes the Svalbard Global Seed Vault an instrumental backup project. So let’s see, how safe is it—and what do you need to do to have your own plant seeds donated there.

How safe is it beneath the mountain?

Long story short, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is designed to protect the gene diversity of plants around the world and keep it for future generations. The project was envisioned in the early 2000s, and the Vault was built in 2008, financed by the Kingdom of Norway. The country spent approximately 9 million dollars to complete this project.

For now, there are a bit more than 1 million samples there. But the Vault can store almost 5 times more. Essential food samples—wheat, rice, corn, etc.—have the highest storage priority. Usually, there are 500 seeds in each sample.