Why today’s democracies are so different?

Most countries call themselves democracies, republics, or both. Yet, they are all different when it comes to politics. So, what does it mean to be a democracy?

Intro: what’s a democracy to begin with?

First, let’s settle the definitions. A dictionary is there to help us.

The word “democracy” has Ancient Greek origins. The word δημοκρατία (dēmokratiā) comes from dēmos—“people” and kratos—“rule.” When combined, these two words make ‘the rule of the people,’ which is the basic definition for a democratic type of governance.

Democracy is a form of government in which citizens (or, to be precise, the majority of citizens) deliberate, elect, and dismiss policies.

The following important concepts are authority (why people obey the government) and legitimacy (why people believe the government has the right to rule). In a democracy, the authority and legitimacy of political power lie in the hands of the people themselves. In the end, it comes to the people to decide on presidents, ministers, policies, and laws. The process of making the decision goes through an election, a referendum, or any other means of a general survey that must be open to the public and media scrutiny.

Other political regimes have their authority and legitimacy stand on different grounds, for example:

- hereditary privilege (monarchy)

- religious beliefs in the leader’s divine origin (theocracy)

- propaganda and excessive use of military or police forces to shut down all who disagree (authoritarian regimes)

- a specific ideology and all-encompassing control of the government (totalitarian regimes).

In other words, we can say, that political power (and the country itself) in a democracy is a public matter—not a private, religious or ideological one. We even have a special word for that: republic (res publica literally means “public affair” in Latin). Nowadays, the word “republic” usually means a country, in which democratic power is realized through elected representatives—more on that in a little bit.

Direct and representative: two ways to act

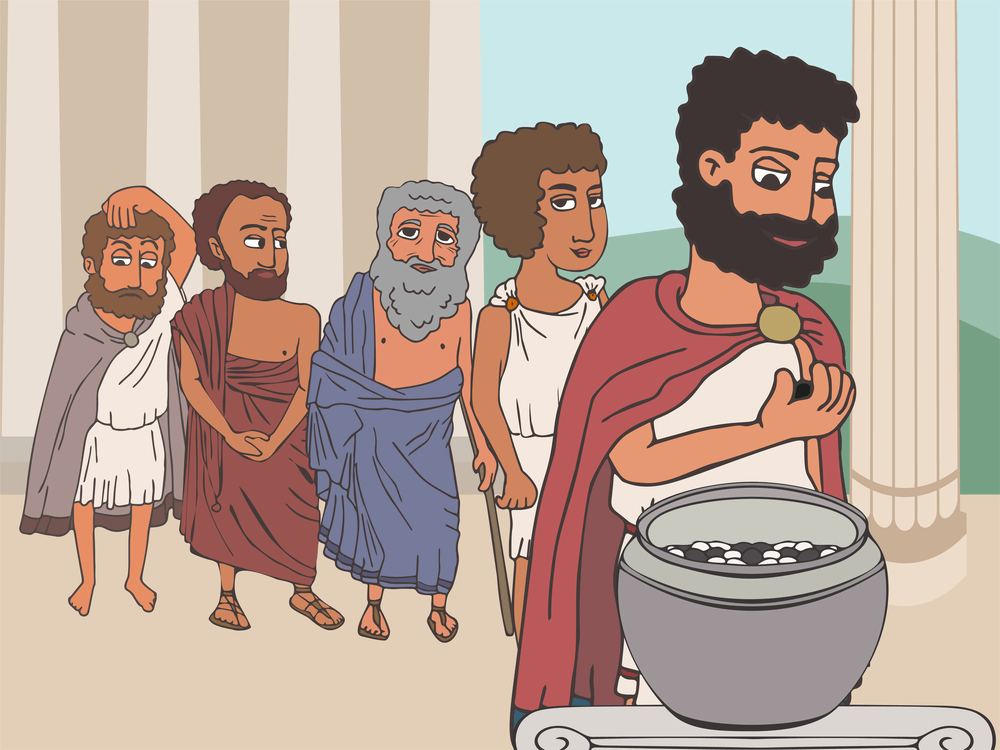

However, democracy right now doesn’t quite look like what it was in Ancient Greece more than two thousand years ago. In Greek city-states, also known as polises, there was a public space called agora, where eligible citizens gathered to judge and decide on laws and their enforcement.

Usually, only male citizens older than 20 years were eligible to participate in these gatherings. And by “citizens,” we mean those born to the citizens of this particular polis. So, women, migrants from other cities, and slaves had no part in the Ancient Greek democracy. Luckily, things have come a long way since then. Course block

Ancient Greek polises were the prime example of direct democracy. Every eligible member of a political community got to influence the policy-making with a vote, decision, or preference. They could choose an acting official—a general to lead an army or an administrator to run a public construction—but they didn’t elect any members of parliament, presidents, or ministers to decide on their behalf. They were in charge of policy-making together with other citizens and neighbors.

In a direct democracy, everyone usually got their chance to participate as an acting official for a certain period by drawing lots. But can a direct democracy exist in today’s world? Not in its pure form.

We still have some elements of direct democracy ingrained within modern political systems. For example, a referendum is when general public votes on a certain issue or piece of legislation.

Referendums happen regularly in Switzerland, where the political system takes up many direct democracy mechanisms. EU citizens can also start a referendum on a general European level—but they have to gather petitions of more than 3 million voters from more than ⅔ member-states.

Referendums can be binding (that is, their results automatically become the law) and non-binding (when the parliament gets to vote on it to pass it as a law).

General voting can also happen in some countries that have a procedure of recall—a majority of citizens who voted to elect an official (for example, a parliament member) can petition to remove them from the office before their legal term ends. Direct democracy works best at a local level . For example, councils in Swiss cantons Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus actually get every resident together to discuss each and every issue until a consensus decision is reached.

However, in today’s world we are most familiar with representative democracy. Virtually every modern state that claims or aspires to be a democratic country is based on mechanisms of democratic representation.

The underlying logic of this system is that not many people can dedicate every day of their lives to politics—and not all of them have the interest in serving the public. So, people delegate these duties and tasks to those who claim to be professionals in policy-making. Citizens cast votes for these representatives, who compete with each other for public trust.

There are three general types of representative democracy, depending on who people get to vote for.

Three types of republics: who gets elected

So, a political regime with regular elections to vote on the state leader is called a republic. Political science separates them into three general groups:

- Parliamentary

- Presidential

- Mixed (also called semi-presidential)

In a parliamentary republic, people primarily choose members of parliament, who in turn appoint government officials: ministers, heads of agencies, etc. Here, parliament usually delegates power to the government (prime minister and their cabinet of ministers) and issues demands. A prime minister failing the expectations can be dismissed by a vote of no confidence from the parliament.

In a parliamentary democracy, the head of state (usually the president, though it can also be a king or queen—we’ll speak of that later) has little political power and is mainly symbolic. The head of government gets to act upon people’s and parliament’s decisions.

Austria, Germany, Italy, South Africa, Switzerland are countries with parliamentary democracies.

In a presidential republic, the president’s office wields power comparable to that of the parliament. The whole nation elects the president, and the winner of the presidential race is assumed to represent the interests of every citizen. The president appoints members of their cabinet and signs laws and bills into action—so, it is not a Parliament that has the final say.

In such democracies, a president usually takes the duties of Commander-in-Chief, being the only one to proclaim peace and war with other countries and act as the most high-ranking representative in foreign relations. It doesn’t mean, however, that the parliament has no real power in a presidential democracy. Many countries have their parliaments check, amend, or veto laws suggested by the president, dismiss members of the president’s cabinet and remove the president who abuses power and turns into a dictator. All these intricate mechanisms are called the system of “checks and balances.” In a genuinely democratic state, it always exists to ensure no single person holds the monopoly on political power.

USA, Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, Argentina are examples of presidential republics without a prime minister. On the other hand, Belarus, Peru, South Korea have presidential systems with a prime minister.

Finally, there are mixed or semi-presidential republics. These countries accommodate both the nationally-elected president and the parliament. The parliament appoints a prime minister and the government, which acts independently of the president.

Poland, France, Egypt, Ukraine, Tunisia, Russia, Syria are semi-presidential republics—with varying degrees of balance between the president and the parliament.

It is important to remember that this division reflects only general categories. There is a great diversity of institutional differences between the countries, especially between the semi-presidential democracies.

For example, in some of them, the president suggests candidates for certain ministers, but the parliament has to back them, nevertheless. In some semi-presidential republics, parliaments don’t have a say in declaring war or peace with foreign states, as armed forces and foreign relations remain in the president’s hands.

All that to say, democracies are all different because people and traditions are different—and there is no easy way to pigeonhole them.