Why we value printed artworks

Not every artwork is created to be unique — some are made to be duplicated many times over. Here we’ll explore the art of making prints.

More than just a copy

Nerdish continues to explore graphic arts. While the topic of drawing deals with graphic artworks made in single copies by hand, this one tells the story of various techniques of image multiplication. You might remember graphic arts to use lines as the main method of artistic expression (as opposed to paintings, which emphasize color). However, this does not stop some of the most famous prints from being full of color.

When we talk about “artworks” and “pieces of art,” we usually assume something unique—even though people can copy the piece itself. There are millions of postcards, t-shirts, and magnets with a Mona Lisa reproduction on them, but they are most definitely not “the” Mona Lisa.

Nobody would stay in a long line to see a life-sized magnet with a Mona Lisa print, even if it’s indistinguishable from the original. And if you tried to sell a copy and pass it as an original—you’d get in trouble for fraud. Original paintings, drawings, and sculptures possess a distinctive quality, a kind of aura that is lost in reproductions—these are the famous words of a philosopher Walter Benjamin.

What should we say about printmaking, then? By definition, prints exist in multiple copies (with some rare exceptions). Also, there is often (but not always) an original drawing that gets reproduced in prints: perhaps, only this drawing can be called an original artwork? Moreover, there are always original plates (made of wood, copper, or other material) from which the prints are made: maybe, only these plates are original? Neither printmakers nor art historians would agree with such a notion.

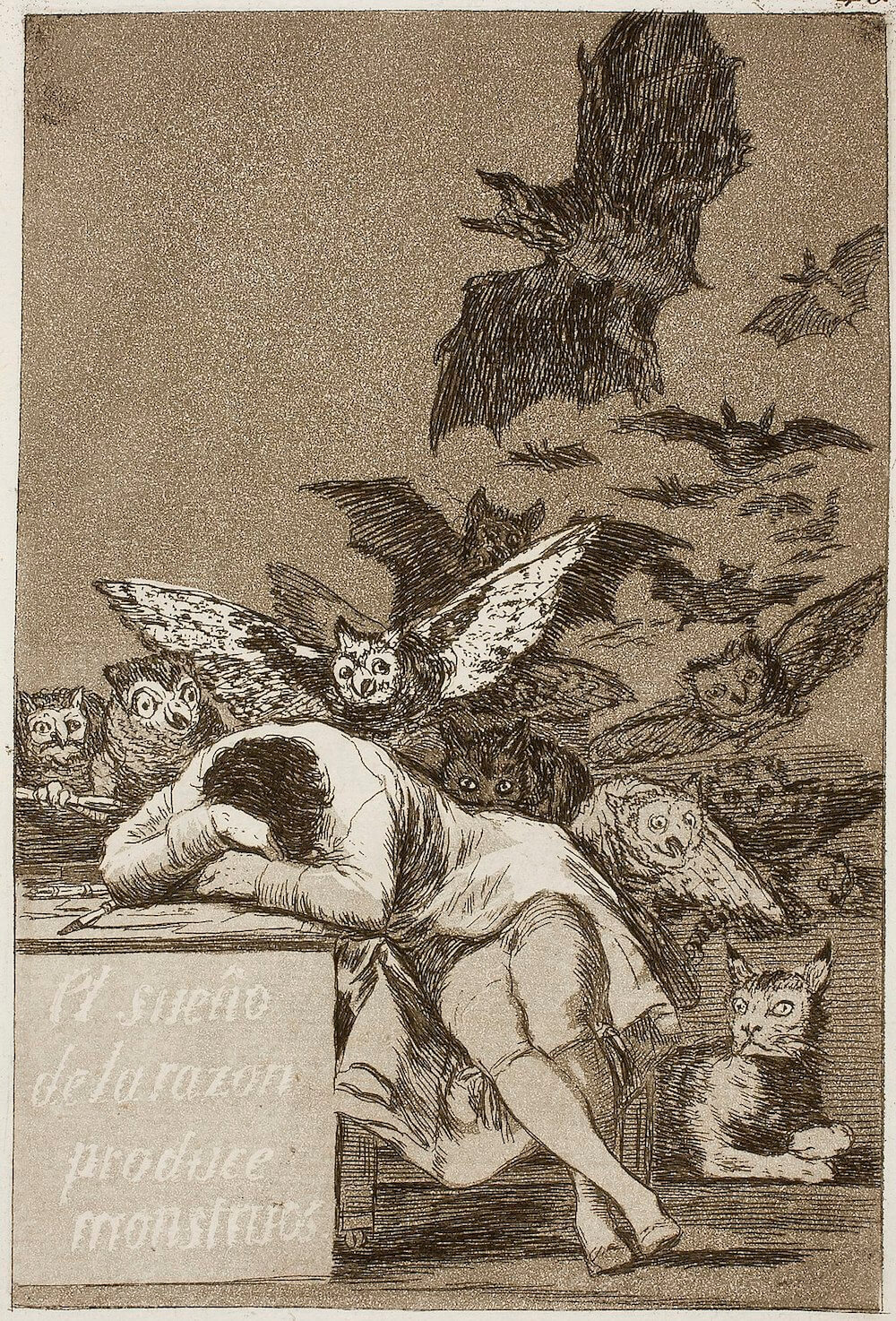

Encyclopedia Britannica suggests a bit of a contradictory definition: the prints exist as multiple originals. So, if I download an image from Goya’s “Los caprichos” collection and print it for my laptop—would it also be an original artwork?

No, because the definition also states that the original artist must be involved in the copying process. They can make everything on their own: an initial drawing, the carving or etching of the plate, and the printing itself. Alternatively, they can leave some parts of the job to somebody else—the copy is still considered an original work as long as the artist supervised the process.

However, even with the artist fully involved, the original print runs can have dozens or even hundreds of printed copies. All original. Do they have the elusive aura Walter Benjamin talked about? We would say yes—as long as they provide means of expression, unattainable in other arts. Prints are not simply copies of drawings or paintings; they have their unique, distinctive features. Each technique and material offers its own creative possibilities, intentionally chosen by a printmaker.

Still, there has always been a tension between making more copies and making the work creatively unique. Thus, the balance can lean in either direction.

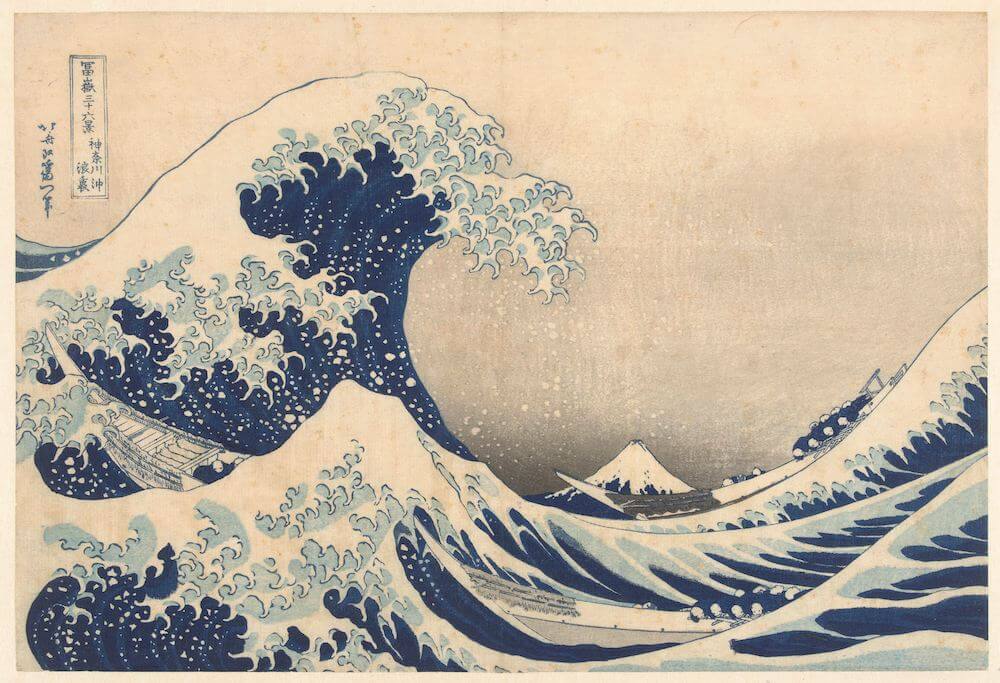

Sometimes it depended on the region: the Western European woodcuts were used mainly for reproductions of drawings, whereas their Japanese counterparts, also from wood, emerged in creative collaboration between the artist, the cutter, and the printer (with the original drawing destroyed in the process).

Sometimes it depended on the origin of a specific technique: the first engravings were made by goldsmiths and armor makers, who created the original design and controlled the whole creative process. Moreover, when a method becomes too popular and commercialized, artists seek new ones that allow more space for experiments: in this way, etching replaced engraving.

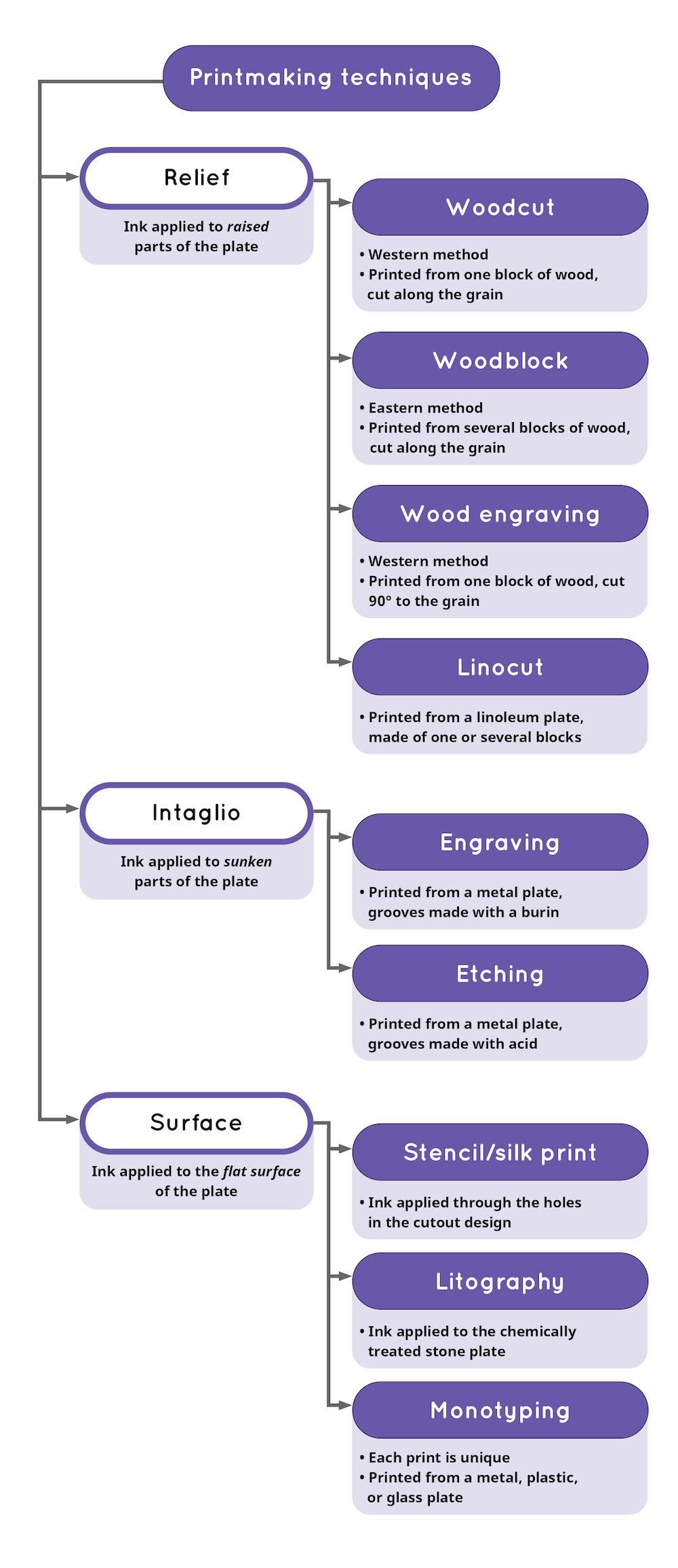

As we explore the various methods, there will be many technical words and explanations. To not get confused, please refer to this chart we made for you. Next, we will provide more detailed descriptions and examples for each technique.

Relief techniques

Relief printing involves a plate with an uneven surface: the ink goes over the raised parts. The process doesn’t require much pressure; thus, an artist can create a copy without using a printing press.

Woodcut

Woodcut is the oldest of all printmaking techniques. The earliest known examples—Chinese prints on silk—date back to at least 220 CE. In Europe, this method emerged in the early 14th century. However, it had not become popular until a century later, when the mass manufacturing of paper started.

The process is relatively simple. Let’s see how it is done in our step-by-step manual.