History of wine: how Europe became the center of world wine-making

Wine comes outside of Europe, yet European wine producers are consistently ranked among the best. Why do we associate wine culture and prestige with Europe? Can it change soon?

Introduction. When and where did wine-making start?

For many years in a row, wine is the most consumed alcoholic drink in the world. A lot of what we know and love about wine drinking we associate with European wines, most famously French and Italian ones. But why do we love it as much as ancient Romans did and still fret over the merits of overpriced Bordeaux for thousands of years? And when exactly did humanity’s love affair with wine start?

At some point 50 thousand years ago, our ancestors climbed the tree to gather grape berries and found them very sweet. They would take them in a container, leave them at home for a while, and in a couple of days, the berries in the bottom would produce a low-alcohol wine. They would drink it, enjoy the slight euphoria, and would do it all over again. This type of accidental discovery was common for neolithic humans, who, through trial and error, began to make food, domesticate animals and crops.

In this topic, we will discover the origins of wine, its ancient roots, and the culture of winemaking and drinking that our ancestors had.

First wine-making nations: why did it all start there?

When humans started gathering grapes on purpose, winemaking got its two possible places of origin.

Rice, hawthorn, various wild grapes, and honey were used in earthenware clay jars to produce alcoholic drinks for religious ceremonies in China around 7000 BC.

The winemaking truly kicked off in the Middle East around 6000 BC, in Fertile Crescent—land surrounded by Taurus, Zagros, and Caucasus mountains, the valley of rivers Tigris and Euphrates. It became a perfect spot for growing crops and developing agriculture, and with it—first civilizations. Grapevine was one of the cultivated plants, and, like in ancient China, it was harvested and fermented in large earthenware jars.

Countries like Georgia, where the oldest found remains of wine date back to 5980 BC, still use those jars, called kvevri.

The remains of ancient wineries were found in Georgia (5980 BC), the northern Zagros Mountains of Iran (between 5400–5000 BC), and Armenia (4100 BC).

The ancient Middle East winemaking was successful not only because of the apt geographical conditions but also because they domesticated a different sort of grapevine than China. Vitis vinifera, or common Eurasian grapevine, is the plant that gave tastier wine and was easier to domesticate—either by sowing seeds or simply lowering a vine into the soil and waiting until new shoots sprang up.

Ancient Egypt: industry, innovation, and pharaohs

From the Middle East, wine spread throughout the region, and the problem of storage and transportation became relevant. Large earthenware jars were incredibly heavy, so a more practical vessel, called amphora, was invented.

In such clay amphoras, the wine trade reached Egypt, around 3200–2700 BC. Wild grapes never grew there, so the drink was not only new and exciting for Egyptians, it made them start a prolific winemaking industry.

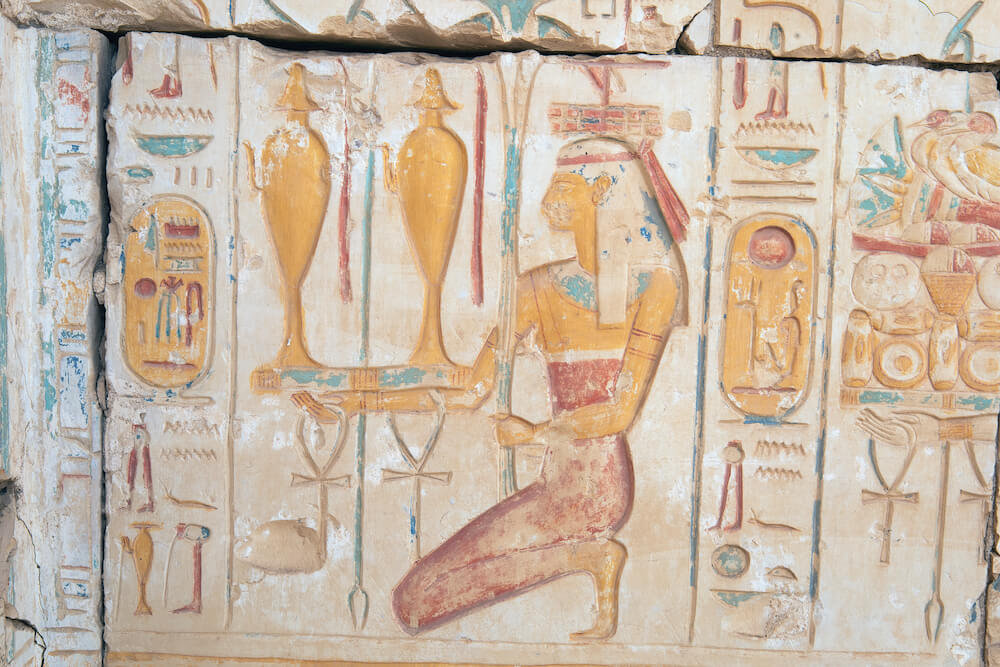

Ancient Egyptian kings and pharaohs loved wine so much they put wine jugs in their tombs.

Red wine was associated with the blood of Osiris, God of resurrection, so for a long time, it was believed Egyptians made red wine. However, jars of white wine were discovered in King Tutankhamun’s tomb, who had a liking to it.

The painted scenes give us a comprehensive view of the process of winemaking and the important adjustments that Egyptians made.

Egyptian technology resembles the modern one closely.

Winemaking basically consists of these stages:

- Harvesting grapes

- Crushing them to extract juice

- Leaving juice to ferment

- Filtration of the wine and preparation for storage

- Storing and labeling

Egyptians, like their predecessors, harvested the grapes at their ripest and placed them in a stonemason. Men crushed grapes by feet, while women sang, played instruments, and kept the rhythm.

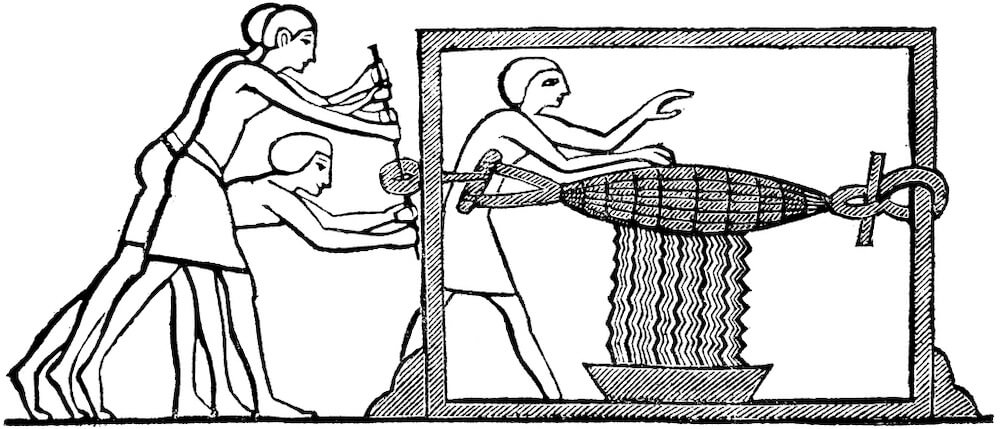

The foot pressure was not enough, however, to squeeze all of the juice from the grapes.

So Egyptians came up with the first version of winepress—placing squeezed grapes into cloth, strung on wood, and twisting it like a tourniquet. After them, every civilization will use a version of it, with Greeks and Romans developing wooden press centuries later.

Extracted juice will be left to ferment. Sometimes, seeds and skins were left to ferment as well—to provide color and aromas for red wines.

The yeast in the grapes is a key to this process: it “eats” the sugars in the grapes, producing ethanol (alcohol) and CO2 as byproducts. The amount of alcohol depends on the amount of sugar.

After fermented juice, called must, reaches a certain percentage of alcohol, the yeast will die, and the process would stop.

Depending on how light or heavy you want the wine, it would be left to ferment for a couple of days or later, several weeks at most.

After active fermentation stopped, wine was drained through layers of linen to get rid of sediment, skins, and solids.

Back then, wine could spoil easily and turn into vinegar, because of unknown yet bacteria. Egyptians tried to prevent that by boiling their wine before storing it in amphoras.

After the sealing, they made a stamp with the information about the wine. The Egyptians included data about the year, the name of the vineyard, the winemaker name, and often the quality of the wine. Special officers or “inspectors of the wine” inspected the wine.

So if we sum up, Ancient Egyptians had a great impact on winemaking. They:

- devised a system of wine-pressing meant to maximize the yield of juice

- knew how to avoid spoiling the wine 4 thousand years before we even knew what bacteria were

- devised our modern labeling system that uses the same information you see on a regular bottle of wine in a store today.

Wine and Ancient Greeks: How a wine-drinking culture started?

From the region of Ancient world wines—China, Armenia, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, and Egypt—vine cultivation spread through the Mediterranean. Sea-faring people of Phoenicia introduced ancient Greeks to the drink, the viticulture (growing the grapevine), and to a deity, which Greeks adopted and called Dionysus.

A nature god of fruitfulness and vegetation, Dionysus is known as a god of wine and ecstasy. Dionysus was the latest addition to Greek Olympians—it hints at its adoption with the winemaking practice.

Later adopted by Ancient Romans as Bacchus, he oversaw wine production and was a reason to give the wine a divine lineage and raise prices.

Greeks loved wine, devoted large pots of land to its growth, and, along with olive and grain, saw it as an accomplishment of their civilization that set them apart from “barbarians”.

In Plato’s Symposium, drunk Alcibiades crashed an enlightening evening of wine and conversation. He could barely stand still and proceeded to drink even more wine. “This is certainly most improper. We cannot simply pour the wine down our throats in silence: we must have some conversation or at least a song. What we are doing now is hardly civilized.”