Ancient Greece: A brief guide to the history, culture and daily life

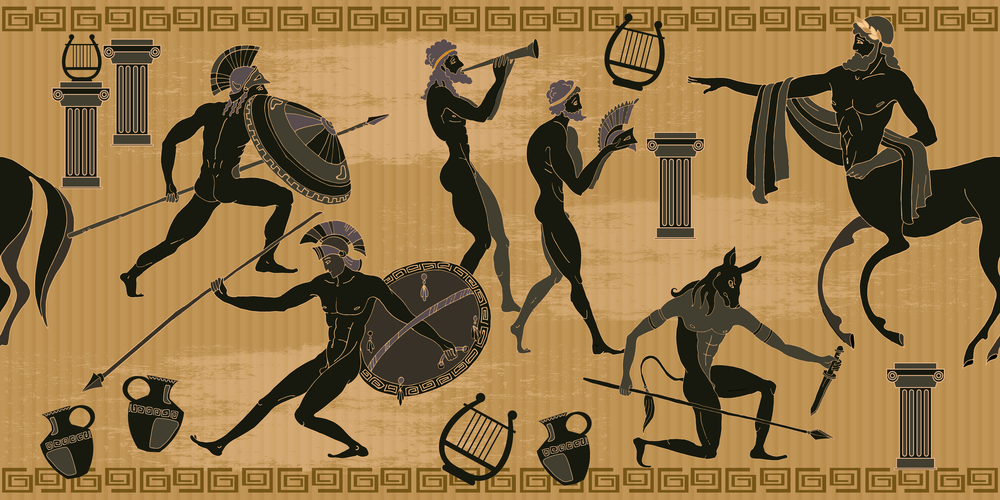

Ancient Greek civilization gave us democracy, theatre, the Olympics, philosophy... But let’s look past their legacy at the people themselves. What were they like?

Firstly, “Ancient Greece” does not denote a single nation-state called “Greece,” with Athens as the capital city. Instead, we use it to describe an extended period with different cultures, cities, rulers, and tribes.

Ancient Greek civilization gave us democracy, theatre, the Olympics, philosophy… But let’s move beyond their legacy and focus on the people themselves. What were they like? In this article, we will delve into the lives and activities of ancient Greek people.

The Ancient Greece: When, Where and How the Greek Empire Existed

We will concentrate on mainland Greece, which includes the southern part of the Balkans with the peninsulas of Peloponnese, Attica, and Chalkidiki projecting from it. The area of Ancient Greece also contains hundreds of big and small rocky islands in the Aegean Sea, as well as the western coastline of modern Turkey (then called Ionia).

Mycenaean Civilization: Writing System and Grandiose Palaces

In general, scholars agree that we can speak of the first culture and civilization that was specifically Greek at around 1600 BCE. It was a mysterious and prosperous Mycenaean civilization that started on the island of Crete. The first Greek civilization emerged when the pyramids in Egypt were more than 500 years old.

Download Our App to Discover More Amazing Storie

Archaeological findings and written texts give us a glimpse at the lives of only rich Mycenaeans. They spent time at lavish palaces with swimming pools and exotic gardens, spending their leisure time in poetry, music, sports, and watching bullfights. We can assume their servants and the poor lived otherwise. However, the serenity and prosperity of the rich were in stark contrast to the “uncivilized” tribes of mainland Greece.

The Mycenaeans invented the first writing system we can attest to the ancient Greek culture—Linear B. It was an update for Linear A, the still undeciphered script used by their predecessors, the Minoan civilization. The scholars have learned to make sense of these ancient plaster slips: they mostly tell how much food, drinks, or cattle different people had.

Greek mythology usually described the past as better times and the future as worse. The Golden times mentioned in the classical Greek myths were the happiest periods of the past—they very much remind the lazy leisure of Mycenaean palaces. Most myths happen around these times. For example, Theseus, king of Athens, travels to the island of Crete to slay Minotaur, a half-man half-bull creature who devoured the brightest young people from the whole of Greece. Minotaur lived in a complex labyrinth where one could easily get lost and die.

Mycenaeans settled the mainland Greece, the coast of Ionia, and the many small islands. They effectively shaped the borders around the Aegean Sea that would later become the nexus of ancient Greek civilization.

In the mainland, unlike Crete, there was a danger of invasion from other tribes and states. The “open space” palaces had to be turned into fortresses with thick stone walls.

Even a thousand years since Mycenaean civilization died out, their Greek descendants still wondered who could have built such grandiose walls and cities. The ancient Greeks wouldn’t believe their grand-grandparents, the Mycenaeans, did this—they thought it was gigantic titans and cyclopes. As the Mycenaeans were waging wars against the surrounding tribes, they also went to war with powerful adversaries overseas. One of their enemies was the city of Troy near the Strait of Bosphorus. Looks like Homer didn’t just make up the tales and legends of his epics Iliad and Odyssey. In the late 19th century, Heinrich Schliemann, a German archaeologist, excavated what is believed to be the ancient city sites of Mycenae and Troy.

Around 1100 BCE, the Mycenaean civilization fell into decline. It soon disappeared: most probably, conquered and destroyed by the tribes from the north of the peninsula. Their writing, arts, big cities, and seafaring techniques were lost. It was an era of dark ages around the entire Mediterranean, known as the Bronze Age Collapse; we don’t know much about what was happening for the next four or five centuries. The population decreased drastically, and the archaeological relics of that time show that people forgot how to paint even the most primitive ornaments.

How Democracy Was Born in Ancient Greece?

About 750 BCE, life got back to usual: the Greeks re-learned seafaring, agriculture, and crafts. In addition, their cutlery and weapons of the time had started to get decorated with abstract ornaments again.

At this time, the Phoenicians were the dominant traders of the Mediterranean. The Greeks interacted with them often, buying grain and building materials. In the hustle and bustle of trading, they exchanged not only material goods: the Greeks adopted their alphabet and transformed it into a new system of writing. Thus the written Greek language was born.

A citizen of, say, Miletus may have had different pronunciation and vocabulary from a citizen of Athens—yet they spoke essentially the same language. In the birth of a single language lies evidence of the Greek culture emerging.

These people populated the entire Greek mainland, the hundreds of islands, and the Ionian coast. They didn’t have a single king or pharaoh ruling over them all. Every independent city-state, called polis, had its own government and laws. So, again, a citizen of Miletus wouldn’t have the same rights when visiting Athens, compared to what he enjoyed back home.

Athens and Sparta were the most renowned polises of entire ancient history.

For the first couple of centuries, Athens was ruled by kings and aristocracy. The wealthy aristocrats reveled at banquets and sports games, while poor peasants and slaves worked hard. Over time, the aristocrats had to give in to some demands, yet social tensions persisted.

After some reforms and revolts, a clan of cunning aristocrats under Peisistratos managed to seize absolute power. Peisistratos and his ancestors were known as tyrants—the Greek word τύραννος means “usurper.” The tyranny didn’t change much of the social structure: people’s dismay was soothed in sports games and public celebrations.

In 514 BCE, two lovers Harmodius and Aristogeiton managed to kill one of the tyrants, heroically dying themselves. After that, Cleisthenes drafted a bunch of laws to transform Athens into a democracy.

Main Principles of Democracy in Ancient Greece

How did their kind of democracy function? People didn’t choose someone to represent their opinion, as we mostly do today. Every male citizen 20 or more years old came to a high hill downtown and had a right to suggest a law or veto one. And yet: women, slaves, and migrants didn’t have any political rights or representation whatsoever.

Ancient Athenian

It could come as a surprise, but an ancient Athenian would say that our modern democracy is an oligarchy—the rule of the few. Today we, the citizens, confer our powers onto politicians. In an ancient democracy, every free male citizen could become a city leader or a military commander, write laws, or object to them.

Ancient Spartans

Sparta had a totally different political evolution. The Spartans were the descendants of those northern tribes that conquered the Mycenaean civilization. They settled down in a mountainous region of the Peloponnesian peninsula and brought other tribes under their control.

Spartans lived in a sort of giant military camp: males lived in barracks together. Women tended their sons only until the age of 7. According to the ancient historian Plutarch, they killed any child who was born weak and unhealthy.

Other city-states had their own political systems: monarchies, aristocracies, oligarchies, tyrannies, etc. But Sparta and Athens would dominate the entire history of ancient Greece—so we look at their lives a bit closer than at others.

Ancient Greek Colonies

Greece is covered with forests and mountains. People in Ancient Greece territory grew olives and wine; they made milk and cheese. But there wasn’t much fertile soil and fields to grow crops. As we’ve told before, they traded with other nations overseas.

Gradually they considered colonizing the lands where they needed to gain food from. Over several centuries, ancient Greeks colonized the entire Mediterranean and the Black Sea, from modern Spain to Ukraine and Russia. The ancient philosopher Plato later would joke that “Greeks sit in the Mediterranean like frogs in the moor.”

The Greeks became the dominant power of the Mediterranean region when the Assyrian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Lydian civilizations fell in decay. Merchants, politicians, and tutors from the coast of modern France to Cyprus spoke Greek. At the same time, Greeks took up inventions and achievements of other cultures. For example, they adopted the technology to mint coins from Lydians, boosting the trade and economy.

The period between 750–480 BCE, known as the Archaic period of the ancient Greek civilization, saw its rise to domination over the whole region. The Greeks settled hundreds of colonies, traveled hundreds of trade routes, and established a plethora of city-states. In this period, Athens and Sparta solidified their own political systems and garnered power.

Meanwhile, the Achaemenid Persian Empire had been looming in the East. By the start of the 5th century BCE, they approached the prosperous Greek cities in Ionia.

Classical Greece Period

The Classical Greece period started about 500–480 BCE when the Persian empire aspired to conquer the Greek polises. First, they invaded and ruined the most prosperous Ionian cities: Ephesus and Miletus. They extorted Athens and its allies, forcing them to surrender and pay vast sums of money. But the combined force of Greek polises defeated the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus claims that Greeks had only 192 casualties, whereas the Persians lost most of the fleet and 6400 dead. Over centuries, another historian Plutarch made a legend that Greeks had lost one more man on that day. An athlete named Pheidippides went as a messenger to run 42,5 km to Athens and tell that the Greeks won over Persians. The legend has it that he ran all up the way and died of exhaustion as soon as he told the news. A 42-km run has been called a marathon ever since.

The Persian emperor Xerxes decided to take revenge in 480 BC. A massive army of thousands of warriors stepped into Greece from the north and went south to reach Athens, Sparta, and their allies.

The invaders could be delayed at a narrow mountain passage called Thermopylae. Buying some time in order for other Ancient Greece polises to prepare for the final battle, the Spartan army went to meet the Persians with 300 “elite” warriors. The warriors made it into a legend of “300 Spartans making their last stand.” The legend, however, conveniently forgets about 6000 Spartan slave-soldiers who also fought near Thermopylae.

In the end, the Persians won that war and burned Athens—but most of the Athenians managed to withdraw to the port of Salamis. The Greeks built a new large fleet, taking new inventions of navigation and engineering. When the Persian fleet came, the allied Greeks defeated the Persians in a sea battle thanks to careful planning. Xerxes decided to come back to Asia, leaving only a part of his army in Greece. The next year the Greeks assembled their resources, training new hoplites—and eventually put an end to the Persian invasions in the battle of Plataea.

Thus the Greeks became the dominant political, economic, and cultural power in the region.

It was the start of the Classical Greece period. After the war, the alliance of city-states remained; as a dominant participant, Athens suggested formalizing it as the Delian League to share the budget and the army. Initially, the polises kept the shared deposit on the island of Delos (hence the League’s name) under the patronage of god Apollo. But soon Athens interfered, suggesting that the League money should be safer under the aegis of goddess Athena. Guess which city-state had Athena as its patron?

The Athenians build a treasury house for the League. On the Acropolis, the central highest hill of the city, near the main market and the government buildings, the shrine to Athena was built—Parthenon, which acted as a central bank for the Delian League. Nowadays Parthenon is considered a symbol of Western civilization, democracy, and Greece.

Athens rose to prominence as the major center of political life, trade, culture, and education. They achieved it largely thanks to the skillful leadership of Pericles, whom Athenians elected many times to stand in the offices of supreme governor and military commander. That’s why the Golden Age of Athens is also called “the era of Pericles.”

Best artists, philosophers, writers, sculptors, and others came to rich polises. Pheidias, a genius of architecture and sculpture, made a beautiful frieze (a large decorated strip of marble on top of the supporting columns) and many statues for the Parthenon and other temples in the city.

Download Our App to Discover More Amazing Storie

The ancient Greeks had already engaged in philosophy since the 6th century BCE: in Miletus, Ephesus, and other Greek cities. But it was in the city of Athens where Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle came to prominence and founded their own schools. Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides—who are revered as founding fathers of modern theatre—lived and worked here, cherished by the public and government alike. The world-famous physician Hippocrates had his doctor’s practice and wrote his famous treatises on medicine there, in the city dedicated to Athena.

Meanwhile, belligerent Sparta recovered from the war against Persians. The Spartans made an opposing alliance with the cities displeased with how Athens usurped the money and power in the Delian League. In 431, BCE they led the Peloponnesian League in a war against Athens. The war was going badly for Athens from the very onset. To make things worse, Pericles died in the outbreak of the plague of 429 BCE.

Sparta besieged Athens on land after subjugating Athens’ allies in the latest phase of the war but couldn’t block the port. The Athenians elected a prominent orator and statesman Alcibiades as the supreme commander; Alcibiades suggested attacking Spartan allies in Italy. The citizens supported this move and gave him the authority and money to prepare the army and fleet to sail to Sicily.

The night before the expedition’s departure, Alcibiades’s enemies staged a provocation. Someone mutilated hermai—statues of god Hermes. The rumors started spreading that this blasphemy was committed by Alcibiades himself. He wanted to be put on trial immediately to clear his name; still, the public urged him to lead the expedition and settle the matters after he returned. However, his political enemies continued the smear campaign against him while he was in Sicily, and he was recalled.

Alcibiades didn’t even return to the city—he defected to Spartans, telling them all the Athenian secrets and war plans. Now Athens lost every chance to turn the tide of the war against Spartans. The city was soon captured, and a peace treaty followed in 404 BCE.

Athens was turned into a provincial city-state under the Spartan governorship; its military and political might were lost forever. Sparta became the dominant force in Greece, but Athens still attracted the brightest minds of the ancient world.

Food, Religion, and Sex in Ancient Greece

Odds are you feel a bit bored with battles, sieges, treaties, and policies. So let’s put wars, heroes, and politics aside to explore the pillars of the ancient Greek society: the meals they enjoyed, the gods they prayed to, and their thoughts about sex.

Make no mistake: ancient Greeks liked feasting. Their ordinary day consisted of three meals, pretty much like most of us now.

For breakfast, they usually had barley bread, which they dipped into wine. You might think: didn’t they get drunk for the rest of the day? Well, ancient Greeks preferred their wine mixed with water in 1:3 proportion, looking down on drinking pure wine as a barbarian addiction. Course block

Lunch for the ancient Greeks was rather a snack than a full-course: they preferred figs, cheese, olives, salted fish, and bread. Again accompanied by wine.

You already know that the Greeks needed to find grains overseas, which was one reason behind the Greek colonization during the Archaic period. But what could they grow in abundance at home? Well, the climate and soil in Greece were perfect for olives, figs, and grapes. But also Greeks were good at animal farming getting meat, cheese, and milk. Besides, as a maritime nation, they were good at fishing.

Finally, dinner was the most important meal of the day. Men liked getting together with friends to dine and discuss politics, philosophy, or art. Women ate separately; if the family didn’t own slaves, women had to serve men first and then sit down to eat themselves.

The ancient Greek dinner usually included fish, legumes, various sorts of cheese (made of goat or cow milk, etc.), vegetables (asparagus, carrots, cucumbers, etc.), eggs—and again barley bread with wine. The richer folk also had meat and desserts—simple cakes and curd with honey. They didn’t use elaborate recipes or spices. They mostly boiled vegetables and eggs and just fried meat and fish.

What were the Ancient Greek Religious Beliefs?

The Greeks believed in many gods, titans, monsters, deities, and spirits. The myths contain most of their reasons to pray, fear, or adore any of those. Greek mythology became the source and inspiration in the Western civilization for many artworks: from music and paintings to poetry and drama.

Metaphysically, Greeks thought that natural forces, the direction of time, the luck in a battle, a game, or an election depended on these deities.

For instance, Zeus was the dominant god, father to many of them, and god of skies—that’s why his anger turned into storms and flashes of lightning. Athena was a goddess of hunting, wisdom, and warfare. Apollo was a god of harmony, poetry, music, and male beauty. In the myths, gods behaved pretty much like humans: they fell in love, took on revenge, expressed jealousy, and engaged in adulterous affairs.

There were many other amusing creatures: half-men half-horse centaurs; the Muses who inspired arts and sciences; and hundred-armed and fifty-headed gigantic Hecatoncheires.

Ancient Greeks revered and cherished their gods to get divine help in the toils and hardships of earthly life. By their beliefs, gods lived on the top of Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece.

By the way, sports and games were as well dedicated to gods. The most famous games, held every four years, were held at the shrine of Olympia (not near the mountain). The Greeks thought the beauty of the body and that of the spirit were related by divine laws.

Olympics winners were celebrities cherished in their hometowns. Gods were believed to have helped the winners because of their natural beauty and talents. Interesting fact: Greeks participated in the games fully naked (but women weren’t allowed to watch).

And here we tickle the topic of sexuality in ancient Greece.

To tell the truth, ancient Greeks were fans of sex and nudity. They believed that a good person couldn’t have an ugly body. Thus, the most beautiful women and men were picked out by gods and touched by the divine. For example, Alcibiades was the most handsome man in all of Athens at the time—he had many lovers, both men and women.

Male homosexuality was an accepted practice, almost a part of education. A young male had to finish his studies and coming-of-age rituals by finding an older patron to explain the unwritten intricacies of adult life. Older tutors often used young boys for sensual gratification. Sometimes the two lovers went on these relationships further. But still, an adult man had to marry a woman and create a family, raising new citizens.

So, the ancient Greek attitude to homosexuality was framed within the public duty to create a heterosexual family as a basic unit of society. However, males often fell in love and had sex with each other, in Athens and Sparta alike.

Female homosexuality wasn’t as much encouraged; however, ancient history knows the example of a female poet Sappho (from the island of Lesbos), who wrote love poems to women and girls. Alcibiades had many male lovers even after coming of age. Harmodius and Aristogeiton were lovers. There is another famous instance of grown-up lovers: Achilles and Patrocles, characters of Homer’s Iliad. In Plato’s dialogue “Symposium” everyone agrees that a male’s affection for another male is more fulfilling in emotions than any relationship between a husband and a wife.

Note, however, that marriage was strictly heterosexual for ancient Greeks—and no one would have thought of same-sex marriage back then. Adult men could have had male lovers on the condition they have a wife and children.

The Decline of Ancient Greece

The 4th century BCE saw most Greek city-states gradually falling into decline. Trade, travel, and economy had never fully recovered from the Sparta—Athens showdown (known to historians as the Peloponnesian War).

In the meantime, a far-off northern Greek kingdom of Macedonia had turned into a mighty military force with burgeoning economics and robust relations with Eastern powers. Even Aristotle, a big celebrity of the time, migrated from Athens to Macedonia to work as a private tutor for Macedonian prince Alexander.

Alexander’s father, King Philip, had started gathering Greek city-states to form “a unified Greece.” In 336 BCE, King Philip was assassinated, and the 20-year-old Alexander ascended the throne. He was not content with just creating a unified Greek kingdom—he also sought to defeat the mighty powers of the East and make the whole world speak Greek. Waging wars for the next 13 years, Alexander and his large army dismantled the Persian empire, overthrew the Egyptian pharaohs, and threatened to expand as far as western India.

Back then, people already had the notion of spherical Earth; however, many still believed that Earth was flat, floating in the endless ocean. When Alexander the Great reached India, he feared that he got too close to the “end of the world,” so he hesitated. His army was quite exhausted and beset with illnesses, so he happily relented.

Alexander expected to be equated with gods and deities of every religion. On freshly conquered lands, he founded several cities, naming them all Alexandria.

When he died unexpectedly in 323 BCE, the empire was partitioned by his successors. Most historians agreed to call this date the end of ancient Greece.

Everywhere he conquered, Alexander encouraged the propagation of Greek culture and language. Mixing and fusing with religions and civilizations of the East, the ancient Greek culture gave rise to the Hellenistic period in the history of the Mediterranean. This period lasted a couple more centuries after the fall of Alexander’s empire—up until the Romans created their own, spanning almost the entire known world.

In the 2nd century BCE, a newly-born Roman republic would annex mainland Greece and—over the next century—the remnants of Alexander’s empire. However, the Greek culture overtook their hearts and minds. The Romans adopted and copied many things from the Greeks: sculpture and architecture, theatre and philosophy, poetry and religion.

Ancient Greece’s Legacy and Achievements

Ancient Greece was a civilization that many believe to have laid a foundation for the modern Western world. It gave us ideas of democracy; theatre in tragedy and comedy; philosophy, and poetry, and impeccable sculpture and architecture.

And there is still much more to it. Although Greeks didn’t invent maths, the works of Pythagoras and Thales were cornerstones of modern geometry. Likewise, Archimedes and Ptolemy are considered the founders of classical physics and astronomy.

It would be wrong to call the ancient Greek culture “superior” to the vibrant civilizations of Levant, Egypt, India, or China. It is not a matter of debate who is better! But ancient Greeks respected and admired beauty, harmony, order, and vitality—and thus created a specific atmosphere where many cherished things could spring out and take root. Many things we now consider essential to modern society trace back to the achievements of the Golden Age of Athens.

We have so much more to tell about specific periods and cities of ancient Greece, about legends, and myths, and heroes, and gods, and philosophers. Each of these matters opens up more and more aspects of the unique ancient Greek culture, of their peculiar civilization that rose upon islands, mountains, and coastlines all around the Mediterranean sea.

And it still has so much influence on us across millennia—thanks to the conquests of Alexander the Great and the Roman assimilation.