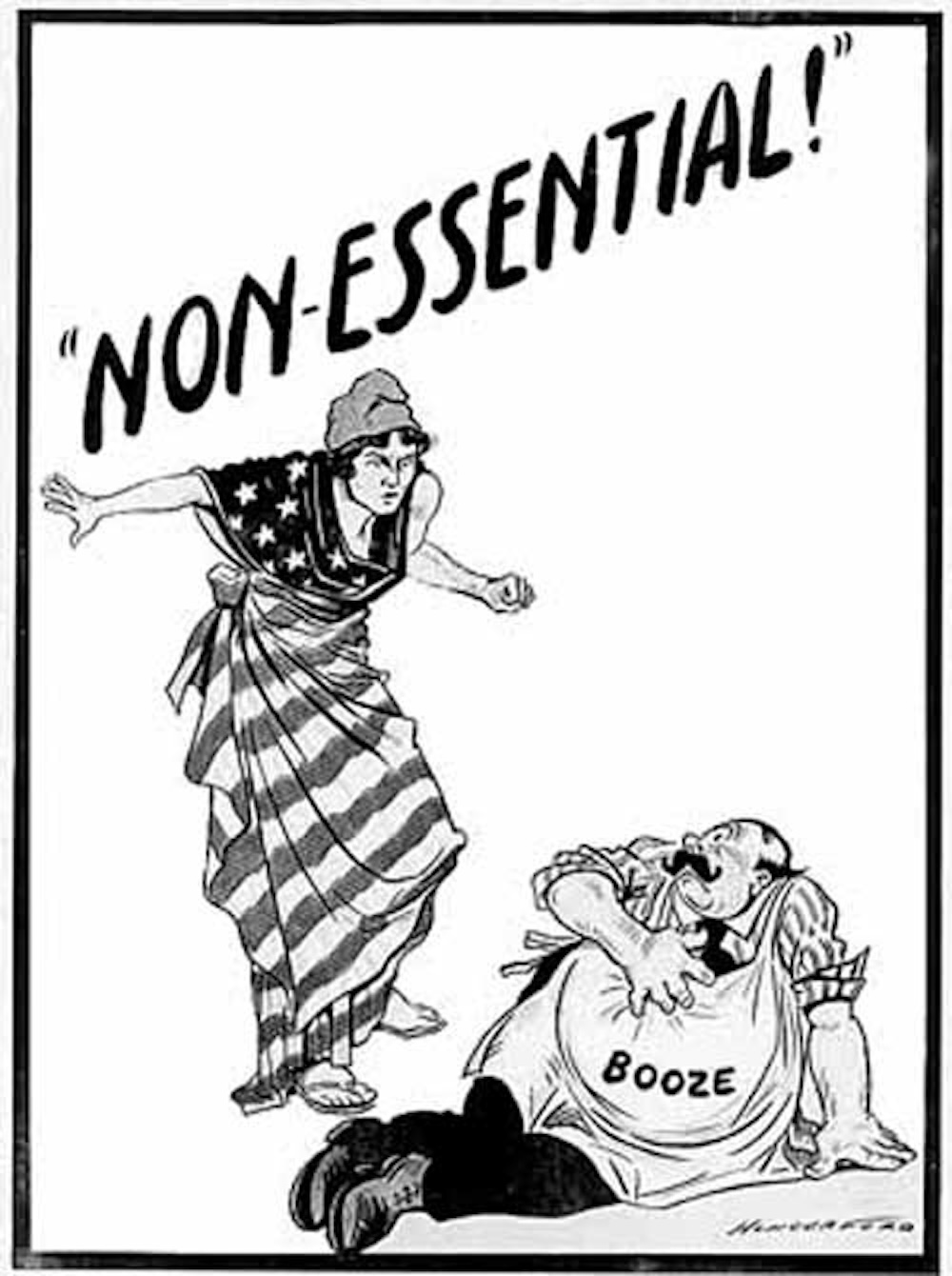

Throughout our history, various societies have attempted to forbid certain substances, from opium and tobacco to marihuana and alcohol. The last has a long record of heavy regulation and banning in the Mongol Empire and Colonial America, Islamic countries, and Christian monastery orders. Perhaps the most famous alcohol ban was the one in the United States in the 1920s, commonly known as Prohibition.

Prohibition was one of the most ambitious social experiments in US history, aimed at eliminating alcohol consumption. This period, intended to foster moral and social improvement, ignited cultural and societal transformation. Far from extinguishing the public’s desire for alcohol, Prohibition fueled the rise of clandestine bars known as speakeasies, where jazz music flourished and new social norms emerged.

It sparked a wave of rebellion that influenced fashion, literature, and entertainment, building a legacy of resilience and creativity in American society. Despite the legal restrictions, Prohibition spurred widespread opposition and fostered a vibrant subculture that altered American culture.

The Prohibition never really went dry.

In this article, we will explain Prohibition, when it started, and how long it lasted. We will discover how it changed American society and what new concepts it introduced.

What is Prohibition, and when did it start? How long did Prohibition last?

The Dry Law in the USA, commonly referred to as Prohibition was a nationwide constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. This period lasted 13 years, from 1920 to 1933, and resulted from a hundred years of movements and campaigns.

In the early 19th century, several movements in the USA discouraged alcohol consumption. The most famous was the American Temperance Society, which argued that alcohol was responsible for many of society’s problems, from crime and poverty to health issues and misguided moral orienteers. The movement heavily relied on churches, like Mormons or Seventh-Day Adventists, with abstinence written in their doctrines. Many Protestants supported Prohibition as well, viewing alcohol consumption as sinful and morally corrupting.

Did you know? The American Temperance Society became so popular that by the 1830s, it already had over 200,000 members.

Another driving force in securing Prohibition was the Woman Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874 in Cleveland, Ohio. The WCTU mobilized women nationwide, organized mass campaigns, educated the public, and successfully lobbied for legislative change. From this point of view, the union demonstrated the significant influence of women’s activism in shaping national policy.

Before Prohibition became a national law, many states and localities had already enacted their own temperance laws. By the early 20th century, several states had implemented statewide bans on alcohol. Finally, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibited manufacturing, selling, and transporting “intoxicating liquors” containing more than 0.5% alcohol by volume. On January 17, 1920, Prohibition officially went into effect.

How did Prohibition change drinking habits in the USA?

The public’s reactions to Prohibition evolved over time, varying from support to opposition to widespread defiance. Some workers protested the dry law because it led to closed breweries, distilleries, and saloons. These businesses had been significant employers, and their shutdown affected many workers and their families.

In response to the enforcement of Prohibition laws, there were riots and violent confrontations all over the country, especially in later years. For example, a notable demonstration was the “We Want Beer” parade in New York City in 1932, where thousands marched to demand the repeal of Prohibition and the return of legal beer.

Despite the legal ban, many Americans continued to consume alcohol. People made drinks at home, such as “moonshine” and “bathtub gin” (called so because it was commonly produced in bathtubs). Some buildings of that time had false walls and secret panels to conceal alcohol. People used to hide liquor inside sofas and wardrobes at home or disguise it in everyday appliances, hollowed-out books, or false-bottomed suitcases.

Bootlegging (the illegal distribution of alcohol) became a lucrative business all over the country, but especially in the cities. The mafia seized this opportunity to control the illicit production, distribution, and sale of alcohol. Mafia groups became heavily involved in smuggling liquor from Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean. They also operated secret distilleries to produce alcohol. The illegal alcohol trade generated immense profits for the mafia, funding other criminal activities such as gambling, prostitution, and drug trafficking.

This era created influential mafia figures like Al Capone. He was the leader of the Chicago Outfit, an organized crime syndicate that controlled much of Chicago’s illegal activities, including bootlegging. His group established a vast network of speakeasies and distribution channels.

At the height of his power, Al Capone reportedly earned as much as $100 million a year from his illegal enterprises (around $1.5 billion worth today). He paid half a million monthly so police and other officials would not interfere (The Mob Museum).

Capone used violence and intimidation to eliminate rivals and maintain control over Chicago’s illegal alcohol trade. One of the most infamous events associated with him was the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre on February 14, 1929. Members of Capone’s gang, posing as police officers, murdered several members of a rival gang.

The mafia ensured a steady flow of illegal booze by supplying underground bars, commonly known as speakeasies. These illicit bars sold alcoholic beverages behind unmarked doors, in basements, through secret wall panels, disguised as soda shops, or accessed via hidden tunnels. The term “speakeasy” originated from patrons being told to “speak easy” about these places to avoid detection by law enforcement. People could enter only with a secret knock or a password (“swordfish,” “Joe sent me,” “forty-two,” etc.)

Raids at speakeasies were common, and proprietors often had to pay bribes to police officers to avoid shutdowns. Over time, many establishments developed sophisticated warning systems and escape routes to evade capture during raids. Some had secret doors, hidden compartments, and false walls to hide alcohol and patrons quickly. Many speakeasies paid the mafia for protection. This involved safeguarding the establishments from police raids and rival gangs.

One of the most famous speakeasies, the 21 Club in New York City, featured elaborate security measures. It had a secret wine cellar with a hidden door and mechanisms to dispose of alcohol quickly in case of a raid. It is estimated that there were around 30,000 speakeasies in New York City alone during Prohibition. To compare, nowadays, the city has around 4000 regular bars.

Prohibition also sparked a revolution in mixology, leading to the creation of many classic cocktails still enjoyed today. For example, many speakeasies popularized the Martini, the Old Fashioned, and the Sidecar. These drinks were often concocted to mask the taste of bootleg liquor and became staples in the speakeasies. In 1929, bootleggers brought around 22,000 gallons of alcohol into 3000 speakeasies in Washington, D.C., every week. (Prohibition in Washington, D.C.:: How Dry We Weren’t by Garrett Peck)

Additionally, Americans often traveled abroad to enjoy legal drinking. Margarita is one of the most famous cocktails from this period. This blend of tequila, lime juice, and triple sec became a favorite among American tourists in Mexico.

What are some notable symbols of American culture we gain from Prohibition?

Prohibition left a lasting impact on American culture, creating some notable symbols and trends that continue to be celebrated today. The 1920s, famously known as the Roaring Twenties, emerged due to post-war euphoria, bringing vibrant energy and cultural dynamism.

One of the era’s most iconic symbols is jazz music, which flourished in speakeasies as hubs of social activity. Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, one of the most influential jazz musicians of the Prohibition era, frequently performed at the Cotton Club in Harlem.

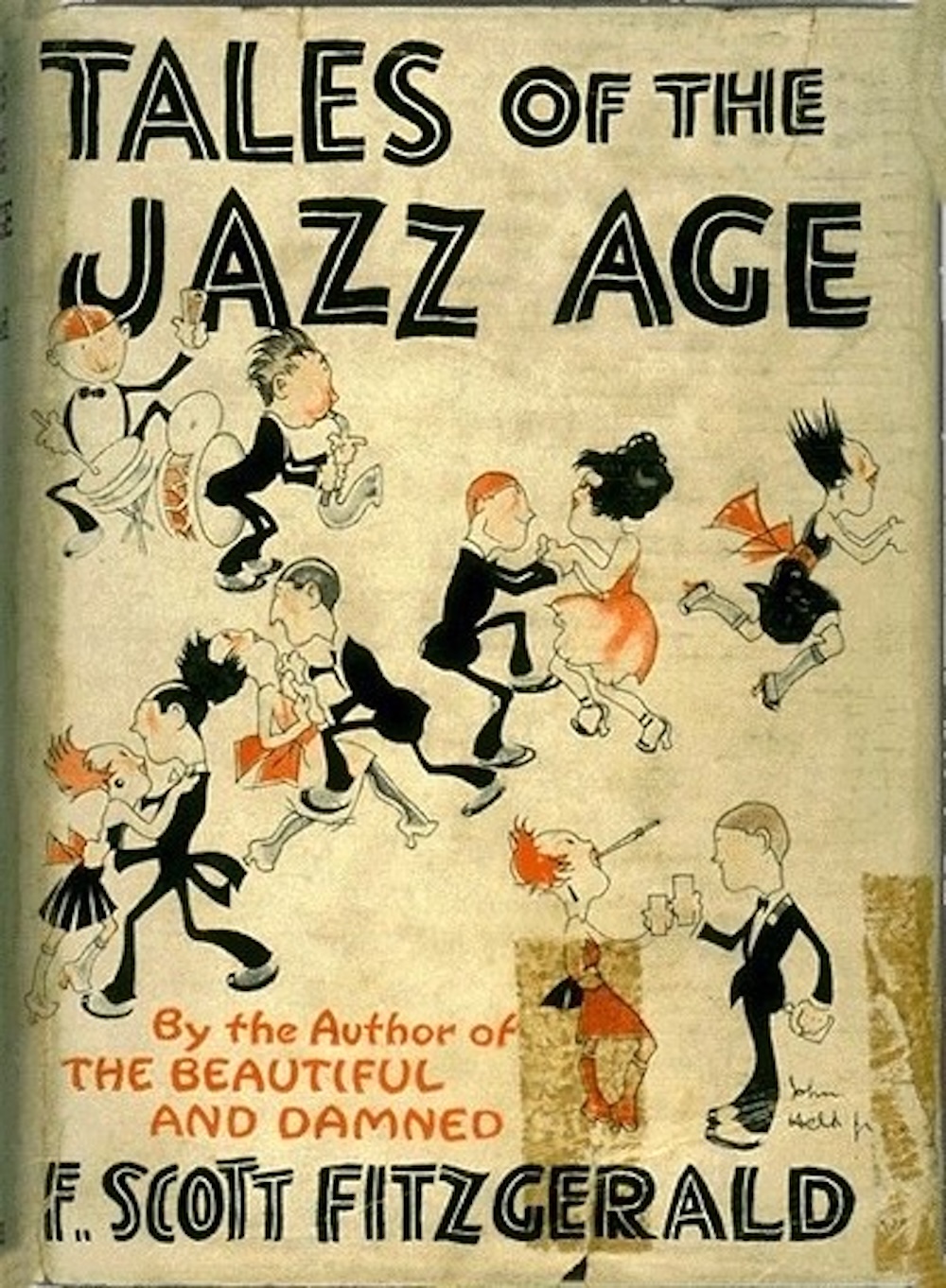

Speakeasies became social playgrounds for numerous writers, like F. Scott Fitzgerald. These bars inspired many literary works, such as “The Great Gatsby,” which captured the decadence and cultural dynamism of the era.

The Roaring Twenties also saw the emergence of flappers, young women who defied traditional norms with their bold fashion choices, short haircuts, and liberated lifestyles. Flappers epitomized the spirit of rebellion that defined the opposition to Prohibition, and they were often found dancing and socializing in speakeasies.

Zelda Fitzgerald, the writer and wife of renowned author F. Scott Fitzgerald, was one of the most famous flappers.

Together, these elements—jazz, the Roaring Twenties, flappers, and influential literature—created some important aspects of American culture that emerged from the Prohibition era. Speakeasies became the backdrop of all this cultural flourishing and society’s resilience to the alcohol ban.

Laws have always shaped how people live — whether it’s the alcohol ban of the 1920s or the customs of ancient empires. Discover what everyday life looked like in Ancient Rome and how Greek culture shaped early democracy and public life.

What happened when Prohibition was repealed?

Prohibition was repealed in 1933. First, beer was legalized on April 7 (now National Beer Day). On December 5, the 21st Amendment was ratified, repealing Prohibition. This new law brought new changes to American society.

The end of Prohibition led to the reopening of breweries, distilleries, and wineries, which had either shut down or turned to producing other products during the dry years. This revival created thousands of jobs in production, distribution, and sales. People were employed as brewers, distillers, bartenders, truck drivers, and in many other roles related to the alcohol industry. These new jobs were critical during the Great Depression.

Did you know?The beer industry alone created 45,000-68,000 jobs in the service sector during the spring of 1933. Beer brewing and distribution created another 35,000 job opportunities (Explorations in Economic History, Science Direct).

With the legal market open again, numerous new alcohol brands emerged. The Prohibition era had already spurred the creation of many cocktails to mask the harsh taste of bootleg alcohol: Martinis, Daiquiris, Margaritas, Manhattans, and Bloody Maries. These drinks became mainstream post-prohibition, with bartenders continuing to innovate and refine mixology as a craft.

The alcohol industry quickly established powerful lobbying groups to protect and promote their interests. Organizations like the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) shaped alcohol-related legislation and regulation. The government benefited from taxing alcohol, which became an important source of revenue, especially during the recovery from the Great Depression. This financial incentive also motivated the government to support the industry’s growth. It is estimated that the US government lost $ 11 billion in tax revenue during Prohibition.

The media started normalizing alcohol consumption. Movies depicted alcohol consumption as a regular part of social life. For instance, classic films like “Casablanca” featured scenes in bars and clubs, showcasing a glamorous view of drinking. Alcohol advertising flourished, with brands using print media, radio, and television to promote their products. Iconic ad campaigns, such as Budweiser’s Clydesdales or Coca-Cola’s association with rum, became part of popular culture.

Alcohol consumption became socially acceptable again, integrated into everyday life and celebrations. Bars, nightclubs, and restaurants flourished as central social hubs. Drinking became a part of various cultural rituals and traditions, from toasting at weddings to casual after-work drinks. Course block Course block