Banana: the world’s most popular fruit?

Crunching the banana numbers

Wherever you live in this world, you’ve most probably had a banana or seen one. Bananas are readily available in any geographical location (except for, maybe, Antarctica). When you think about fruits, chances are that bananas are the first thing that comes to mind.

So, does it mean that bananas are the first among fruits in the world?

Technically speaking, not exactly. If we are talking production numbers, number one is a tomato—and yes, tomato is considered a fruit by botanists (although nutritionists still count tomatoes as vegetables). The planet grows about 180 million tons of tomatoes yearly. Bananas come second with 120 million tons, followed by watermelons and apples (about 100 million and 80 million tons respectively).

So, the answer really depends on how you slice it. While some highbrows may not agree with you, it is perfectly fine to exclude tomatoes from fruits. And if you do, bananas indeed become number one!

The highbrows can’t argue with one thing, though: bananas are the most popular when it comes to international trade. Almost 20% of all produced bananas go to export, which amounts to global trade of 14 billion dollars a year. On the other hand, the tomatoes’ trade tally is only 9 billion.

Whereas Asia is the largest producer of bananas (with India holding the crown among all countries), Latin America and the Caribbean region are the biggest exporters. The biggest importers are the USA, Germany, and Japan (though we still couldn’t find any numbers about Antarctica).

Read on to discover what makes bananas so tradeable, explore the variety of more than 1000 types of bananas, and marvel at how people use them besides just eating.

Note: Bananas aren’t the only everyday food with a surprising past. Check out the journeys of ketchup, wine, and coffee. And if you’re into bold flavors, here’s why spicy food has such a devoted fan base.

What makes bananas so desirable, importable, and shippable?

Although banana plants are usually called trees, the botanists once again come to mess things up: by their classification, banana is a herb.

Scientifically speaking, the plant belongs to a genus called Musa. Its stem might look woody—but actually, it is made of huge leaf stalks.

Musa is native to Southeast Asia, and it mainly grows in warmer climates across the world. Its fruit—a banana—contains fiber, potassium, antioxidants, vitamins C and B6, and phytonutrients, making it an important food crop. Someone might have told you that bananas are radioactive. If so, relax. Technically, it is true: bananas are rich in potassium, and some of that is an unstable isotope K-40 that emits a tiny bit of radiation. However, you have much more potassium in your body (compared to a banana), so you are “radioactive” on even a higher level. Thus, the bananas’ radiation won’t harm you in any way—as well as that in spinach, salmon, avocados, and mushrooms, which are also rich in potassium.

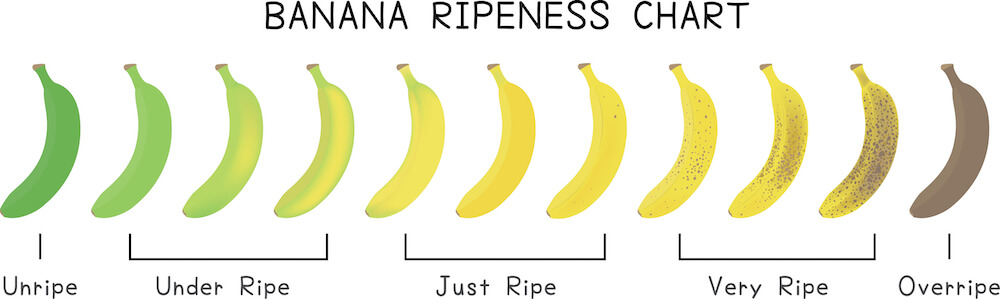

Before a banana can reach you in a general store, it goes through various stages. After seedlings are planted, sprouting takes around 2 to 3 months; the flower appears in the sixth month. When the fruits become light green (from 9 to 12 months after planting), they are reaped.

Whereas many plants are seasonal, bananas can be collected all year long, growing in tropical and subtropical regions.

After the bananas are harvested, most of them go to local markets. However, some of them are transported to a pressing plant for export: there, the fruits are washed with water, arranged, gauged, and packed. When bananas are packed in a cardboard box, a number is placed on the case. This number is the personality code, which recognizes the farm where the banana was reaped, the pressing office, the date, and the pressing season. It then goes through a phytosanitary review or a similar trade assessment and is finally ready for shipping.

It requires a long time for bananas to cross the sea: up to two weeks. The fruits are transported in containers that keep the environment cold and ventilated.

Remember that bananas are harvested green? After arriving at a destination port, they are usually sent to a “ripening room”—a warehouse where ethylene gas is added. Ethylene gas is a natural hormone that stimulates the ripening process. Because of that, bananas continue to mature even after they get to a store shelf.

A thousand types of a banana

The plant Musa has about 70 wild-growing species in the scientific classification. However, most commercially cultivated types come from only two species: Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana, or their hybrid, called Musa paradisiaca. And even then, they are products of careful selection.

It is difficult to estimate the exact number of these cultivated types—the names are often confused, even within one country. Sometimes different bananas are attributed to one type, or a type is called many names. In general, there are from 300 to more than 1000 cultivated types.

However, one type is produced and consumed the most on the planet: the Cavendish banana, which accounts for about 47% of global supply and the vast majority of international trade. The name of Cavendish banana comes from Duke William Cavendish, who received a shipment from the island of Mauritius and cultivated them in his garden at Chatsworth House in the 1830s.

The Cavendish banana is your ordinary neighborhood banana, found in supermarkets or farmer’s markets. It is somewhat sweet and has a smooth surface.

Cavendish banana crops can achieve high yields per hectare and, due to their short stems, are less damaged by storms and adverse weather. They are also known for their fast recovery from natural disasters.

However, as with most cultivated bananas, it has a problem with reproduction. Due to being seedless, they are not pollinated—new plants are grown by vegetation, creating an exact genetic clone. Because of that, this cultivated type has a weak genetic pool and is highly susceptible to outbreaks of disease.

In fact, the previously most traded banana type, Gros Michel, was nearly wiped out in the 1950s by Panama disease—a fungal plant infection that started spreading in the early 20th century.

In the past years, a new strand of Panama disease has been on the rise, threatening the world’s population of Cavendish bananas. So in the future, producers might switch to other types: for example, the honey-flavored Pisang Raja, the light-pink Red Bananas, the delicate and smooth Lady Fingers, or the “ice cream banana” Blue Java that has a rich vanilla taste. The researchers in Honduras have recently developed a new cultivation type of banana called Goldfinger as the “new Cavendish.” This type resembles Cavendish in many respects but is more resistant to diseases and can be cooked when green.

Yes, bananas can also be cooked! The cooking types are called “plantains,” and they are usually not that good when raw. However, they are rich in starch and make for savory dishes.

Plantains are a regular staple food in the West and Central Africa, Central America, and the Caribbean Islands.

Not only food

Yes, sometimes a banana is not just a banana—you might vividly remember that from your sexual education classes.

However, besides eating, bananas are much more helpful than elongated demonstration tools. Banana fiber from stems and leaves has been used for various purposes at least since the thirteenth century.

Banana fiber has been a decorative element and a construction material throughout entire Asia. Banana shoots and leaves produce strands of varying delicateness. For instance, the peripheral filaments of the shoots are the coarsest—and are reasonable for decorative spreads.

The mildest deepest strands make for cloth. The Japanese craft of Kijōka-bashōfu—making cloth from banana fiber—is recognized as an essential part of the country’s cultural heritage. This delicate cloth does not stick to the body in hot climates. The famous Japanese poet and master of haiku Matsuo Bashō got his name from a banana plant. The “bashō” planted in his nursery by an appreciative understudy turned into a wellspring of motivation to his verse, a symbol of his life and home.

Banana stems and peels are good at making paper. This paper is more robust, disposable, and renewable than traditional paper and can be used as an ecological alternative for packaging.

Bananas also have a religious significance in some cultures. In India, bananas serve a noticeable part in numerous Hindu celebrations and events. In South Indian weddings, especially Tamil weddings, banana trees are tied two by two to symbolize the couple’s long and durable life.

According to Thai folklore, a particular species of a wild banana plant is inhabited by a spirit Nang Tani that looks like a youthful woman.

Bananas have time and again found their place in the world of arts and music. The popular song “Yes! We Have No Bananas”—a response to one of the first outbreaks of Panama disease, which caused a shortage in 1923—was the smash hit of printed music for a long time.

The media-famous artwork “Comedian” by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan—a banana duct-taped to a wall—was made in three copies. Two of them were auctioned at a museum in Miami Beach for $120 000 dollars in 2019.

While the piece was still exhibited, another artist ate the artwork, calling it an intervention entitled “Hungry Artist.” He was asked to leave the exhibition but got into no further trouble—and the eaten banana was replaced later that day.

Eventually, the media attention around the artwork and its selling price attracted large crowds. The exhibition organizers decided to remove the piece, afraid that other art would get damaged in the commotion. In their statement, they said that this banana “with its simple composition, ultimately offered a complex reflection of ourselves.”

Pretty good for a simple banana, don’t you think?