The History of Wine

For many years in a row, wine is the most consumed alcoholic drink in the world. But when exactly did the history of wine start? In this article, we will discover the origins of wine, its ancient roots, and the culture of winemaking and drinking that our ancestors had.

When and where was wine invented?

When humans started gathering grapes on purpose, winemaking got its two possible places of origin.

Rice, hawthorn, various wild grapes, and honey were used in earthenware clay jars to produce alcoholic drinks for religious ceremonies in China around 7000 BC.

The winemaking truly kicked off in the Middle East around 6000 BC, in Fertile Crescent—land surrounded by Taurus, Zagros, and Caucasus mountains, the valley of rivers Tigris and Euphrates. It became a perfect spot for growing crops and developing agriculture, and with it—first civilizations. Grapevine was one of the cultivated plants, and, like in ancient China, it was harvested and fermented in large earthenware jars.

Countries like Georgia, where the oldest found remains of wine date back to 5980 BC, still use those jars, called kvevri.

The remains of ancient wineries were found in Georgia (5980 BC), the northern Zagros Mountains of Iran (between 5400–5000 BC), and Armenia (4100 BC).

The ancient Middle East winemaking was successful not only because of the apt geographical conditions but also because they domesticated a different sort of grapevine than China. Vitis vinifera, or common Eurasian grapevine, is the plant that gave tastier wine and was easier to domesticate—either by sowing seeds or simply lowering a vine into the soil and waiting until new shoots sprang up.

Winemaking in Ancient Egypt: industry, innovation, and pharaohs

From the Middle East, wine spread throughout the region, and the problem of storage and transportation became relevant. Large earthenware jars were incredibly heavy, so a more practical vessel, called amphora, was invented.

In such clay amphoras, the wine trade reached Egypt, around 3200–2700 BC. Wild grapes never grew there, so the drink was not only new and exciting for Egyptians, it made them start a prolific winemaking industry.

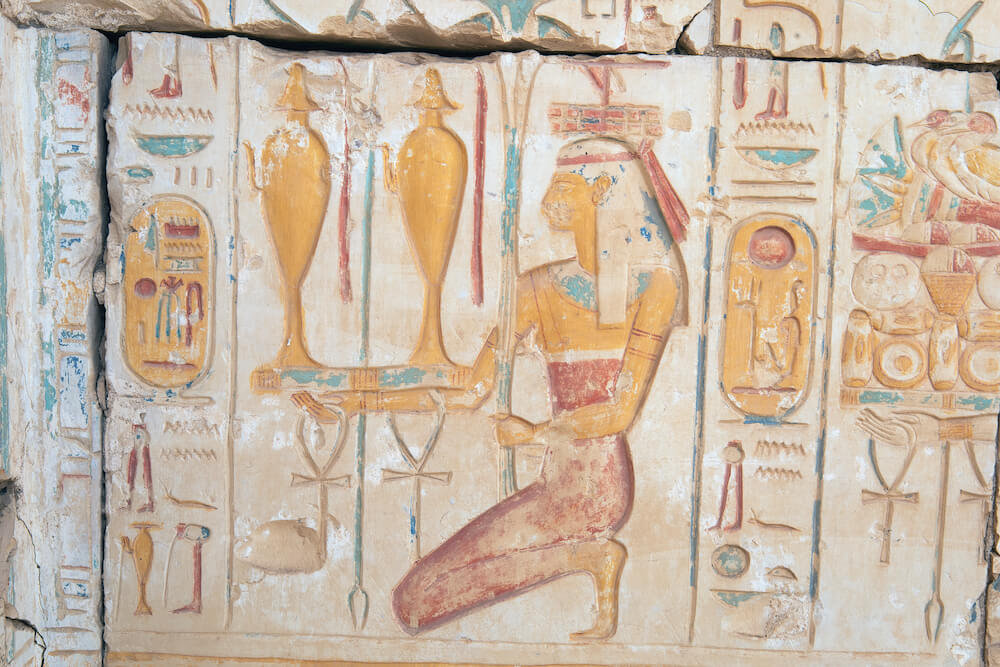

Ancient Egyptian kings and pharaohs loved wine so much they put wine jugs in their tombs.

Red wine was associated with the blood of Osiris, God of resurrection, so for a long time, it was believed Egyptians made red wine. However, jars of white wine were discovered in King Tutankhamun’s tomb, who had a liking to it.

The painted scenes give us a comprehensive view of the process of winemaking and the important adjustments that Egyptians made.

Egyptian technology resembles the modern one closely.

Winemaking basically consists of these stages:

- Harvesting grapes

- Crushing them to extract juice

- Leaving juice to ferment

- Filtration of the wine and preparation for storage

- Storing and labeling

Egyptians, like their predecessors, harvested the grapes at their ripest and placed them in a stonemason. Men crushed grapes by feet, while women sang, played instruments, and kept the rhythm.

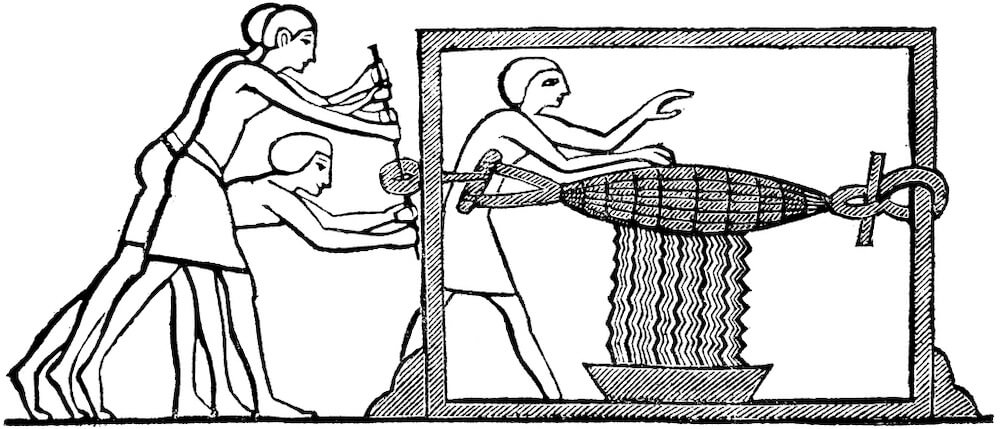

The foot pressure was not enough, however, to squeeze all of the juice from the grapes.

So Egyptians came up with the first version of winepress—placing squeezed grapes into cloth, strung on wood, and twisting it like a tourniquet. After them, every civilization will use a version of it, with Greeks and Romans developing wooden press centuries later.

Extracted juice will be left to ferment. Sometimes, seeds and skins were left to ferment as well—to provide color and aromas for red wines. The yeast in the grapes is a key to this process: it “eats” the sugars in the grapes, producing ethanol (alcohol) and CO2 as byproducts. The amount of alcohol depends on the amount of sugar. After fermented juice, called must, reaches a certain percentage of alcohol, the yeast will die, and the process would stop.

Depending on how light or heavy you want the wine, it would be left to ferment for a couple of days or later, several weeks at most. After active fermentation stopped, wine was drained through layers of linen to get rid of sediment, skins, and solids.

Back then, wine could spoil easily and turn into vinegar, because of unknown yet bacteria. Egyptians tried to prevent that by boiling their wine before storing it in amphoras.

After the sealing, they made a stamp with the information about the wine. The Egyptians included data about the year, the name of the vineyard, the winemaker name, and often the quality of the wine. Special officers or “inspectors of the wine” inspected the wine.

So if we sum up, Ancient Egyptians had a great impact on winemaking. They:

- devised a system of wine-pressing meant to maximize the yield of juice

- knew how to avoid spoiling the wine 4 thousand years before we even knew what bacteria were

- devised our modern labeling system that uses the same information you see on a regular bottle of wine in a store today.

Wine and Ancient Greeks: How a wine-drinking culture started?

From the region of Ancient world wines—China, Armenia, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, and Egypt—vine cultivation spread through the Mediterranean. Sea-faring people of Phoenicia introduced ancient Greeks to the drink, the viticulture (growing the grapevine), and to a deity, which Greeks adopted and called Dionysus.

A nature god of fruitfulness and vegetation, Dionysus is known as a god of wine and ecstasy. Dionysus was the latest addition to Greek Olympians—it hints at its adoption with the winemaking practice.

Later adopted by Ancient Romans as Bacchus, he oversaw wine production and was a reason to give the wine a divine lineage and raise prices.

Greeks loved wine, devoted large pots of land to its growth, and, along with olive and grain, saw it as an accomplishment of their civilization that set them apart from “barbarians”.

They brought innovation to the process in the form of the wooden winepress, attributed to god Dionysus himself.

The wine was important for Greeks economically, so they even put grapevines and leaves on their coin. Greeks sold their knowledge of viticulture and winemaking and the fruits of their production to Cyprus, Egypt, Scythia, Etruria, and beyond.

So, what was a typical Ancient Greek wine party?

For starters, they wouldn’t drink wine like we do and would even look down on us. The wine Greeks made was very young, under one year, so it was sweet and potent. Greeks, like Egyptians before them, mixed it with water, spices, honey, and raisins. It also helped to mask the scent of spoilage if it occurred.

Wine drinking is described in detail in Iliad and Odyssey as an intricate ritual essential to every meal. It had to be accompanied by music or conversation. Drinking just for its sake was considered uncultured and undignified.

Diluting their wines also meant that they could keep drinking it through hours of inspired conversation without getting inebriated. In a social gathering, the potos—ritual of wine drinking after a light dinner consisted of drinking diluted wine. In this way, the participants could go on with discussions, which are immortalized by poets, without getting drunk.

In Plato’s Symposium, drunk Alcibiades crashed an enlightening evening of wine and conversation. He could barely stand still and proceeded to drink even more wine. “This is certainly most improper. We cannot simply pour the wine down our throats in silence: we must have some conversation or at least a song. What we are doing now is hardly civilized.”

Ancient Romans in the history of wine: How did they make European wine what it is nowadays?

As we move into the 2nd century BC, Rome emerged with the scope of influence that will soon cover all of the Meditteranean.

Their culture adopted the Greek god Dionysus who became Bacchus. Wine no longer was the privilege of the elite, but a daily necessity for every Roman, dictated by law.

Wine production became a full-blown industry, advanced through technological breakthroughs. The wooden press was improved, wooden barrels were utilized, which allowed longer, compared to clay amphorae, storage, and transportation of the wine.

Roman conquest meant that wine should have been available to Roman soldiers. To grow grapevines in colonies made more sense than to attempt massive transportation. That is how winemaking regions of modern-day France (the Gaul invasion result), Germany (conquest of Germania), Portugal, Spain, Italy were established.

Romans believed in democracy and thought that wine should be distributed democratically.

The wine was, in various forms, made available to slaves, peasants, and aristocrats, men and women alike. It created a great demand that fuelled the production and also gave birth to wine culture.

Romans had a real passion for vintage vines, with mature examples from older vintages fetching higher prices. While today a prized bottle of Bordeaux of the century can go off for thousands of dollars, in Roman times, Falernian wine was considered the best.

Only three vineyards produced Falernian wine from grapes that grew on the Mount Falernus slopes. It received a cult status, even gaining divine lineage. It was said that the vines were planted by Bacchus himself as a reward for a farmer (aptly named Falernus) who showed him hospitality.

Falernian was appreciated for its aging ability. This wine needed at least ten years to mature and has been at its best between 15 and 20 years.

The sky-high prices and exclusive status of the wine meant that only the richest of patricians, as well as emperors, could afford it. Numerous authors, including Galen and Horace, described wines of certain years, notably Falernian from 121 BC, as the vintage of a lifetime. Some wrote about tasting it 200 years after the harvest, though Pliny the Elder in the 1st century admits that the wine was a bit past its prime then.

Falernian wines were prized for their taste, but also the status as the symbol of luxury, so a lot of “fake” Falernians were sold at the market. It also was one of the reasons for the first-known laws that protect the authenticity of wines, such as the DCOS we see today.

If Falernian was the most expensive wine on the menu, then what did the regular citizens drink?

Posca, a combination of water and sour wine that had not yet turned into vinegar. It still retained some of the aromas and texture of wine and was not acidic. Roman soldiers preferred Posca because of its low alcohol levels.

Slaves would drink Lora (modern-day Piquette), which was made by soaking in water for a day the pomace of grape skins already pressed twice and then pressing a third time. Both Posca and Lora were the most commonly available wine for the general Roman populace. Those were red wines since white wine grapes were reserved for the upper class.

Middle Ages & Monasteries: How Monks Shaped the History of Wine

After the 3rd century AD, monasteries sprang up all around Europe. From Italy, France, and Germany to Asia Minor, Northern Africa, and Spain.

Since the wine was an important part of the Eucharist (also known as communion), there was a constant need in its production, which came into disregard in northern countries.

While the south of Europe widely produced wine, northern countries grew it seldomly because of dependence on the temperature and conditions.

The most notable monastic orders that were involved in winemaking were the Benedictine monks. Benedictines were one of the largest producers of wine in France and Germany, and also Carthusians, the Templars, and the Carmelites.

The Benedictines owned vineyards in Champagne (Dom Perignon was a Benedictine monk), Burgundy and Bordeaux in France, and Rheingau and Franconia in Germany. They established many of the world-famous wines like Bordeaux, Riesling, Burgundy, and sparkling wine Champagne.

The monks studied grape cultivation and created a system where the soil, exposure to the sun (as the morning sun was most beneficial for vines), climate, and altitude were taken into account when choosing a plot of land for vineyards.

Monks also observed that planting grapevines on the slopes with limestone sediments, volcanic residue, clay particles, chalk, gravel, which were formed over thousands of years and combined with different micro-climates makes unique diversity of expression within the wines.

Such planting of grapes on the slopes is not only beneficial for the soil, which is well-draining because of all that gravel, clay, chalk. It also gives optimal sun exposure, protection from strong winds and rains.

The monk orders throughout Europe developed such an efficient system of wine production that the Church managed to become the biggest supplier of wines, not only for the use in the Eucharist.

Many of the world-known wineries that are still operating now were also established at that period, such as Château de Goulaine est. in 1000 in the Loire Valley.

It was the way the monasteries earned money—supplying wine after a deficit caused by the fall of the Roman Empire.

Thus formed our notion of old-world wines—mainly European, North African, Near Eastern sorts.

American Wine History: Did winemaking exist in the Americas before colonization?

Yes and no. The grapevine has already existed in the Americas, but people have not used it for alcoholic fermentation.

Alcoholic beverages were made by the indigenous people of Mexico and Central America long before the European invasion. Before the European conquest, there was no significant tradition to make fermented or distilled beverages north of Arizona and New Mexico. Alcohol’s effects were largely unknown throughout much of North America.

People made spirits from crops, fruits, and cultures native to the land: corn, potatoes, quinoa, pepper tree fruits, strawberries, and different species of evergreen, flowering plants, cacti.

Spanish conquest marked the beginning of the plantation of Vitis vinifera, with the first attempt done on the island of Hispaniola during the second voyage of Columbus in 1494.

After the invasion and conquest of Mexico by Hernán Cortés, the Spanish government promoted the establishment of the vines. By 1524, every Spanish settler needed to grow vine if he wanted to acquire land in the Mexican plateau. Later, the cultivation of vines started in Peru, specifically in the city of Ica, from where it spread to Chile and Argentina.

These countries cultivated Spanish sorts of vine. The most common vine planted in these territories was a black grape called Mission. It was grown in Mexico and later in Texas and California. Same grapes were planted in Peru under the name Peruvian black, becoming the source of the most commonly used vine in Chile: the Pais.

Why did South American countries succeed in winemaking?

If we look at the modern map of wine-producing countries in South America, the top-5 looks like this:

- Argentina

- Chile

- Brazil

- Uruguay

- Peru

This list coincides almost entirely with vineyards, first planted by Spanish settlers. Why were these territories so successful in growing grapevines?

Argentina, Chile, and Peru are on different sides of the Andes mountains. This creates an optimal dry and arid climate for the Vitis vinifera, a common grapevine.

Most of the vineyards lie at higher elevations with plenty of sunshine. They are irrigated by the snowmelt from the top of the mountains, which makes the soil favorable and does not require artificial watering.

Argentina is the largest South-American wine producer. But Argentina wasn’t always in the lead. In fact, from the 1500s to the 1800s, wine production was slow. The rates of production began to rise after the French grape variety of Malbec was introduced.

In 1830, the Mendoza region in Argentina had only 2500 acres (1,000 hectares) of vineyards. By 1910, the number rose to 11,200 acres (45,000 hectares). Today about 80% of all vineyards in Argentina are cultivating vinifera vines—mainly Malbec, which became Argentina’s signature wine.

Malbec, one of the grapes permitted in the Bordeaux blend, was not a valuable variety. At one point, the experimentation with planting Malbec at the incredibly high altitude of the Mendoza region started. The results allowed Argentina to reach new heights in Malbec production and elevate its status far beyond what the European counterpart of the grape was able to do.

Peru became a very productive wine region in the 16th century, producing so much wine at one point that they imported it back to Spain. That caused a threat to the native wines, so King Philip II of Spain eventually placed restrictions on wine produced in the Americas to protect all wine producers and merchants from Spain. That ban ended up hurting Mexico more than other Spanish colonies in the Americas.

On the other side of South America, the Portuguese conquest caused the first attempts at viticulture in Brazil. The vines were planted there in 1532 in San Paulo. Like at that time in Europe, vineyards often were managed by monastic orders. After the destruction of the Jesuit orders that controlled most of the vineyards, wine production would not be restored until the 18th century, when a new wave of immigrants from Azores and Madeira arrived.

Brazil did not have the same climatic conditions as Peru, Argentina, and Chile. Its equatorial and very humid climate is not optimal for the grapevines growing. So, until the vineyards moved to the South of the country to the Rio Grande do Sul in the mid-1850s, there was no real success.

Today Brazil is the third-largest producer of wine in Latin America, after Argentina and Chile.

How did California become the heart of North American wine production?

Before the European conquest in the 15th–16th century, Vikings sailed to coastal North America as long as 1000 CE. The variety and abundance of grapes grown there created the name Vinland (Winland) for the territory.

However, wine made from that grape had an unfamiliar and unpleasant taste to the first settlers.

That is why all following settlers grew familiar varieties of vitis vinifera, European grapevine.

Out of Spanish vineyards planted in Texas, Mexico, and California, the latter was a real success.

Today California is the center of winemaking in the USA, responsible for almost 84% of all wine produced in the country. But how did California become the success story of North American wine?

Vineyard planting in California began in 1769 with the Spanish Franciscan Missionaries: Mission San Diego de Alcalá. Just like before, monks planted vines for their use in communion, along with palm trees needed for Palm Sunday. The grape planted by missionary Junipero Serra throughout the state became known as the Mission grape. Commercial production was originally centered in Southern California.

The Gold Rush (1848–1855) brought an influx of people to Northern California. The demand for wine increased significantly, prompting the establishment of vineyards in Sutter, El Dorado, and Napa counties. Amongst many others, they are nowadays the wine centers in Northern California. Grapes were not only Spanish but a mixture of many European sorts that people brought to the state during the Rush.

As Prohibition started in the 20th century, many wineries managed to survive by making wine for religious use—much like in the Medieval Middle East. The cultivation of grapes for domestic use grew, but the quality of them suffered as people replaced them with tough but poor quality grapes such as Alicante Bouschet and Alicante Ganzin.

It wasn’t until the 1970s when California increased wine production and quality significantly by implementing the system of origins, similar to what the Europeans have.

As for native North American grapes, an effort to plant them in European soil would be made in the 19th century, with disastrous consequences that nearly destroyed European vineyards (we’ll come back to it later).

How did South Africa establish one of the most coveted wineries in the world?

Today South Africa is one of the most prominent world wine producers—not only in volume but in the quality and exclusivity of their wines.

Unlike North and South America, where wine culture was established by Spanish and Portuguese settlers, the South African wine industry was started by people with relatively small wine history in Europe—the Dutch.

In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck arrived in the Cape of Good Hope with three ships and a task of establishing a supply station for the Dutch East India Company, capable of producing fresh provisions for Dutch ships heading east. Initially, the planting of the vines in Wijnberg (Wine Mountain area) was meant to make wine that could potentially ward off scurvy for sailors continuing on their voyages along the spice route.

Riebeeck’s successor, Simon van der Stel, brought improvement to the process of viticulture and farming. He established the site of Constantia that grew into the world-known vinery. Constantia wines became a firm favorite among European royalty by the 18th century. Van der Stel imported many grapes from Europe. The Austrian Muscat, for instance, became eponymous with Constantia wines.

The Dutch had almost no wine tradition until the French Huguenots settled at the Cape between 1680 and 1690, and the wine industry began to flourish. As religious refugees, the Huguenots had very little money, so they had to adapt their established winemaking techniques to new conditions.

To protect grapes from the gale winds of the Cape, people planted oak trees along the vineyards. They adopted official decrees that dictated the harvesting of the grapes when they were ripe, their fermentation in clean barrels, and implementation of various standards of quality.

All that made Constantia the first New World Wine to enjoy international acclaim, as well as a reputation of quality across Europe.

The Groot Constantia (“Great Constantia”) wine still exists today. Through the 18th–19th century, French oenologists (wine scientists) had placed it in the highest category at the quality classification of the world wine.

Australia and New Zealand. Why the best Sauvignon Blanc is not French

The cuttings from the South African Cape of Good Hope were brought to the penal colony of New South Wales (East Coast of Australia) in 1788.

The first attempts at winemaking in Australia were unsuccessful. Only with the perseverance of other settlers and the trial of different varieties they managed to cultivate vines for winemaking successfully. By the 1820s, and Australian-made wine was available for sale domestically.

Throughout the 19th century, the Australian wine industry slowly progressed when settlers learned to work in an unfamiliar climate that resembled Meditteranean in its hot, dry temperatures.

The production and quality of Australian wine improved after the arrival of free settlers from various parts of Europe. They used their skills and knowledge to establish some of the premier wine regions in Australia.

Prisons are a big part of Australian history, and wine history is no exception. The New Wales colony was a prison one, where many Irish convicts were sent during the 19th century.

Australia also benefited from different varieties of vines brought from regions like Prussia and Switzerland. That’s why one of the Australian specialties nowadays is Riesling, a white grape variety commonly grown in Germany.

Australian wines were widely acclaimed in international competitions, especially their Syrah (also called Shiraz), although unfairly slighted in favor of the old world French provenance.

In 1836 some of the cuttings of Australian vines were taken to New Zealand, establishing its first vineyard. Nearly 200 years later, descendants of his original cuttings are still thriving in vineyards throughout Australia and New Zealand.

Missionaries that arrived in New Zealand also planted vines for communion wine; some of those wineries are still active.

Before the 1970s, the now world-famous Marlborough region of New Zealand was covered by sheep-grazing. In 1975 Daniel Le Brun, a Champagne maker, emigrated to New Zealand to begin méthode traditionelle production in Marlborough. Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc made its breakthrough in the 1980s and 1990s to the delight of wine critics and consumers around the globe.

The region responsible for 75% of New Zealand wine production also is the 2nd largest producer of Sauvignon Blanc in the world.

If the history of wine fascinates you, you’ll also enjoy learning about how coffee became a cultural phenomenon and the surprising journey of ketchup from fermented fish sauce to modern tables. And don’t miss how the banana became the world’s most popular fruit — it’s a wild ride.